Giving felt the boot

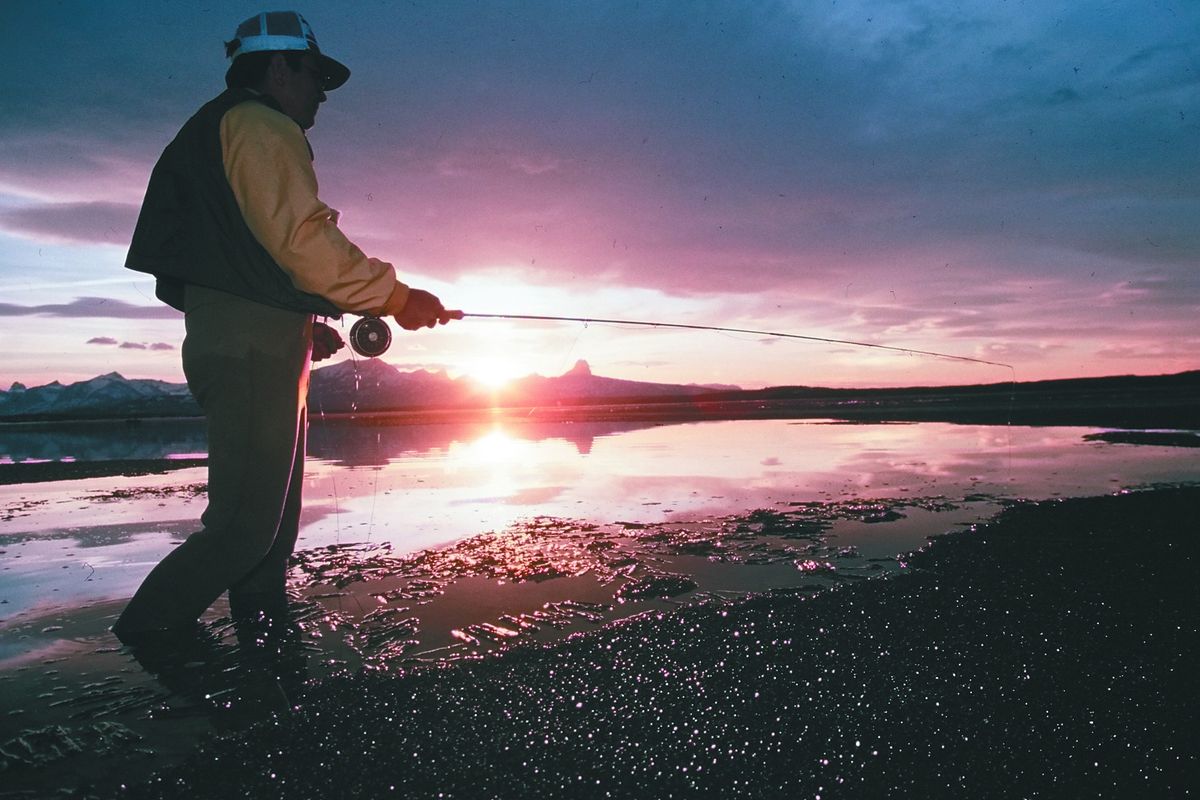

Anglers get a grip on issue of rubber versus felt wading boots

With invasive species beginning to raise havoc in North American waters, some anglers and fishing gear companies are taking a holistic approach to prevention, starting with their boots.

Simms, a Montana-based fishing gear manufacturer, took a bold step from the competition last year by announcing it was eliminating venerable felt-soled wading boots from its line.

“Boots aren’t the only issue, but they’re a great ground-level place to start the conversation about other gear and boats and the impacts we have on our streams,” said Matt Crawford, Simms publicist.

Felt is revered for giving anglers traction on otherwise slick rocky stream bottoms.

But the dense mat of randomly woven fibers that works so well at gripping moss-covered rocks also is an ideal trap for any small material. The silt that sifts out in an angler’s vehicle and closet for weeks after a fishing trip is just the most visible sample.

Scientists have shown that felt also is remarkable at trapping, preserving and transporting nastier debris that can infect fish and infest streams.

Researchers from Montana State University as well as Canada and New Zealand have probed the felt soles of wading boots and found evidence of unsavory characters, including:

•The pathogen for whirling disease, which crippled some of Montana’s prized trout populations in the 1990s.

•Didymo, a single-cell algae that’s forming slimy globs known as “rock snot” on previously pristine trout waters worldwide.

•New Zealand mud snail, an exotic species that’s infested lakes and rivers in 20 states since being detected in the United States in 1988.

David Kumlien, Trout Unlimited’s specialist on invasive species and former executive director of the Whirling Disease Foundation, stirred up some mud when he wrote the conservation group’s policy statement in 2008 calling for anglers to kick their felt-boot habit.

“We’d been talking about it for a decade and New Zealand had just become the first nation to enact a ban on felt boots,” he said in a telephone interview from his home near Bozeman. “Some states were looking into it and we were seeing research verifying our concern.”

Alaska and Vermont recently approved felt-soled boot bans starting next year.

“Prior to the TU policy, anglers were not engaged in the issue,” Kumlien said, noting that boaters were involved because of education and regulations dealing with the spread of zebra and quagga mussels that can take over boat launches and ruin boat motors.

“But many anglers figured invasive species were somebody else’s problem,” he said.

Simms’ daring move to eliminate felt boots was facilitated by a new generation of “sticky rubber” compounds and tread designs.

“Aquastealth was an early product that turned a lot of anglers off to the idea,” Kumlien said. “It wasn’t very good – like roller skates on mossy boulders.”

New rubber compounds are much improved, said Kumlien and four guides interviewed for this story.

Highest praise leaned toward the Vibram soles used in the Simms StreamTread line and the Orvis EcoTraX, which uses the same rubber in a different tread design.

Ryan Barba, owner of Sunrise Fly Shop in Melrose, Mont., said the boot performance varies from river to river. For example, the Simms and Orvis boots work well in the mossy Beaverhead River, he said, but not so well in the Big Hole’s notoriously slippery rocks.

“I fish a lot,” Kumlien continued. “I fish as much as anybody you know – over 120 days a year in a lot of water types – and I was an outfitter for 30 years. I can tell you that these new rubber soles with (removable) cleats or studs work every bit as well as felt or better.”

Changing the minds of some anglers seems almost as hopeless as the crusade to convert winter drivers from studded tires to modern sticky-rubber treads.

Online fishing chat rooms swell with accusations that there’s no science to indict felt for transporting invasive species, that it’s a plot so fishing companies can sell more wading boots, that it’s a slippery slope toward more government regulation.

Some anglers question the controversy over felt soles since invasives can harbor in other parts of a boot.

“Laces and stitching are easily dried or treated with a bleach solution or the cleaning agent 409,” said Larry Dalton, aquatic invasive species coordinator for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

“Felt soles cannot be reliably cleaned or treated and they don’t dry in a reasonable amount of time, allowing invasive species to live inside and be translocated. Thus, get rid of the felt soles! There is good comparable performance product out there.”

Officials assigned to deal with invasive species share a similar sense of urgency.

“Felt boots are just a scratch in the surface in the complexity of this issue,” said Joe Starinchak, invasive species outreach coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Overall, I don’t think anglers or politicians necessarily understand. Disinfecting must become a fact of life for anglers and boaters.

“People hate government regulation, so we’re hoping that the private sector can use its marketing know-how to get the point across,” he said, adding a stern notice:

“Invasive species are the single biggest threat to biodiversity and we have barely begun to address their effect on all of us, not to mention our fish and wildlife.”

“Felt has been around for so long, it’s hard to change the status quo,” Kumlien said. “Trout Unlimited is not trying to push for regulations. We simply provide the scientific background for states and agencies looking into this.”

Kumlien said TU’s goal is to get anglers on board for risk reduction.

“There’s no way to eliminate the risk. So what do you do? You do what you can.

“I would not fall on my sword if somebody said they were going to keep using felt, but I’d try to make them aware of what they are doing.”