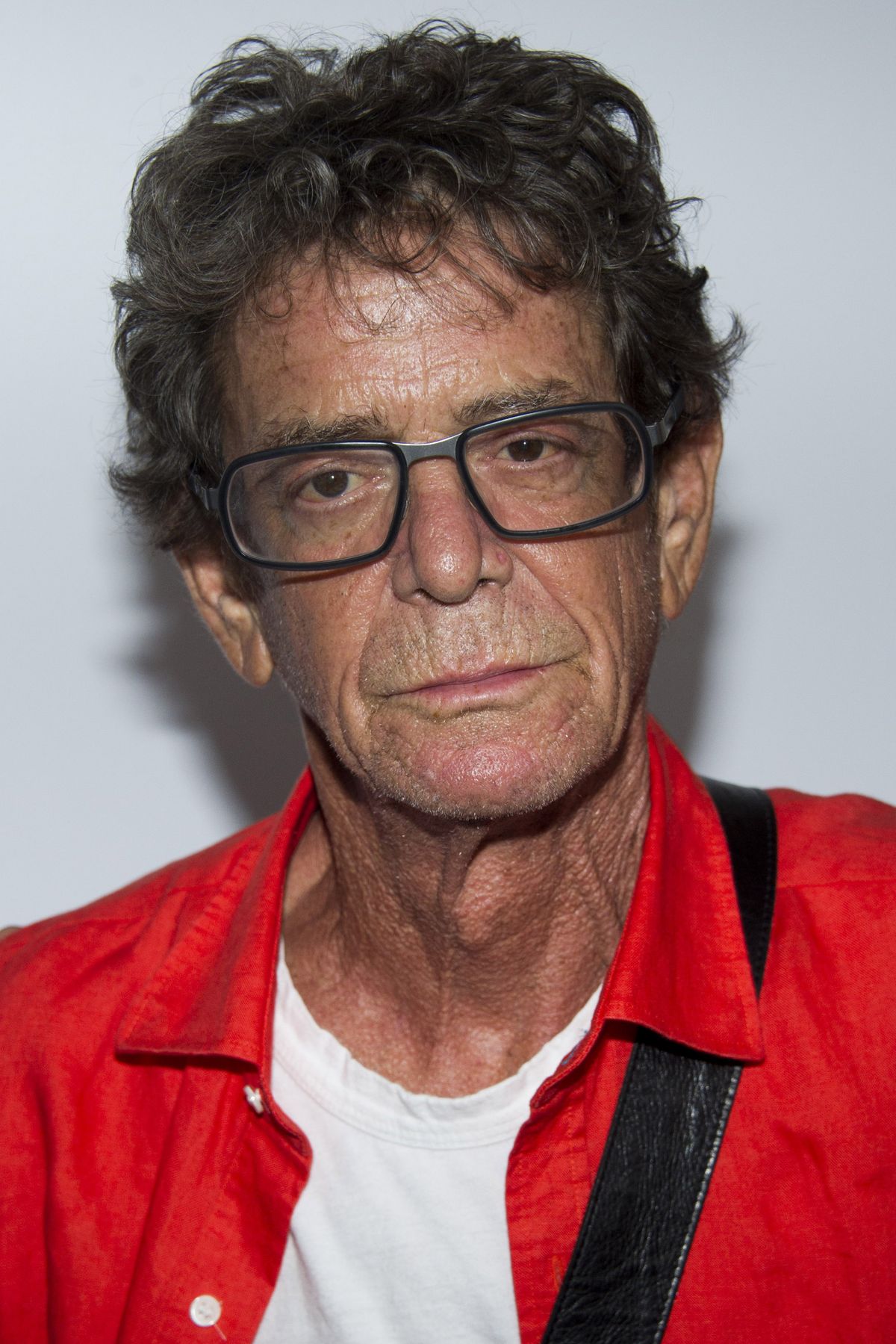

Through Reed, underground rose to spotlight

Unflinching honesty, unrelenting sound made mark

LOS ANGELES – Those looking for one version of Lou Reed’s life need look no further than to the late critic Lester Bangs, who presented a particularly harsh, if affectionate, take on the artist’s story in a single sentence.

“Lou Reed is the guy that gave dignity and poetry and rock ’n’ roll to smack, speed, homosexuality, sadomasochism, murder, misogyny, stumblebum passivity, and suicide, and then proceeded to belie all his achievements and return to the mire by turning the whole thing into a monumental joke …,” wrote Reed’s longtime sparring partner Bangs in 1975.

Reed, who died on Sunday at age 71, offered a simpler biographical snapshot within his most famous song, advising that listeners “take a walk on the wild side.”

Starting in the mid-1960s, the co-founder of the Velvet Underground and longtime solo artist helped set rock ’n’ roll on a different course, injecting into the music’s vocabulary then-taboo themes that had largely remained hidden in dungeons, junkie dens and the writings of the Marquis de Sade.

Reed and early bandmates John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker delivered work variously featuring screeching feedback and meditative guitar mantras, droning viola, metronomic drumming and gently strummed lullabies. After lineup shifts resulted in the Velvet Underground disbanding, Reed poked at guitar rock from countless angles for the rest of his life, tackling major and minor projects to varying degrees of success.

But he’ll forever be known first as the voice of the Velvet Underground.

From a commercial perspective, the band was a flop. But in the decade after they split, the Velvet Underground’s work was rediscovered by a new generation, one for whom Rolling Stone magazine’s baby boomer history involving Elvis, the Beatles, Woodstock and the Summer of Love had become a fixed, often eye-roll-inducing narrative. While the Beatles experimented with LSD and weed and offered coy hints in “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” Reed and band were examining dissonance with “Heroin,” a stark song about injecting the opiate and the rush that accompanies it.

Reed was the snake with the apple, bringing into rock’s lexicon new thematic temptations – “Venus in Furs,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Lady Godiva’s Operation,” “The Gift” tackle harsh truths – and fresh textures of noise.

In this graininess, though, Reed could cast glorious colors: “Linger on, your pale blue eyes,” he sang in the ballad “Pale Blue Eyes.” In the roaring “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” he wrote of “hand-me-down clothes from who knows where” while a runaway band delivered glory. On the 17-minute dirge from 1968 “Sister Ray” he celebrated a big sailor “dressed in pink and leather – he’s just here from Alabama,” and helped birth punk rock.

So wide and varied was his career that Reed’s major achievements deserve chapters: “Velvet Underground & Nico,” the 1967 debut album “produced” by Andy Warhol. “Venus in Furs” helped birth gothic rock. “Candy Says” is heartbreaking. Even the oft-dismissed Velvet Underground album “Loaded” contains perfection. “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll” are some of Reed’s most enduring works.

As a solo artist, Reed became the king of downtown cool, a man so confident in his cred that he could market a Honda scooter to make it look (almost) as dangerous as a Harley-Davidson. He made failed stabs at commercial albums in the 1970s and ’80s, and even Reed acknowledged their artistic shortcomings. (“Sally Can’t Dance” notwithstanding, though, Bangs’ characterization of his solo oeuvre as a “monumental joke” mostly overstates their failures.)

But throughout his artistic life, Reed delivered many perfect moments, ranging from the exquisite full-length “Berlin” to the polarizing experimental concept “Metal Machine Music” (four sides of disorganized noise). “The Blue Mask” is a truly weird rock album.

Reed also tackled big concepts: His chunky guitar album “New York” is an ode to his city. He adapted Edgar Allan Poe for his 2003 album “The Raven.” He and Cale collaborated on a work about Andy Warhol called “Songs for Drella.” His final record, perhaps unsurprisingly, was one of his most controversial: “Lulu” adapted an Edwardian text about a prostitute and featured Reed in league with Metallica. The critics mostly hated it. But go back and listen to the last song, “Junior Dad.” It’s a typically intense capstone.

That Reed’s death was announced on a Sunday morning came as bittersweet news to those of us for whom “Sunday Morning” is the closest thing to a hymn we’ve got.

For many, Reed fed a craving that we didn’t know we had. Others passed judgment; he reveled in the grit that interested him, and though some cast his expressions as too difficult or depressing, Reed disagreed.

“I don’t see it as the dark side,” he told the Los Angeles Times’ Richard Cromelin in 1978. “If this was a novel or a movie, this stuff would be no big deal.” Describing basic rock parameters as “horrifyingly narrow,” Reed rejected those strictures. “If you do anything other than pure, surface optimism, you seem to come off as intrigued with the dark, murky, kinky, down side of existence.” Ultimately, Reed concluded, “It’s just a little realism.” American music was forever changed because of it.