Window to the mind

Autistic artist’s work part of First Friday

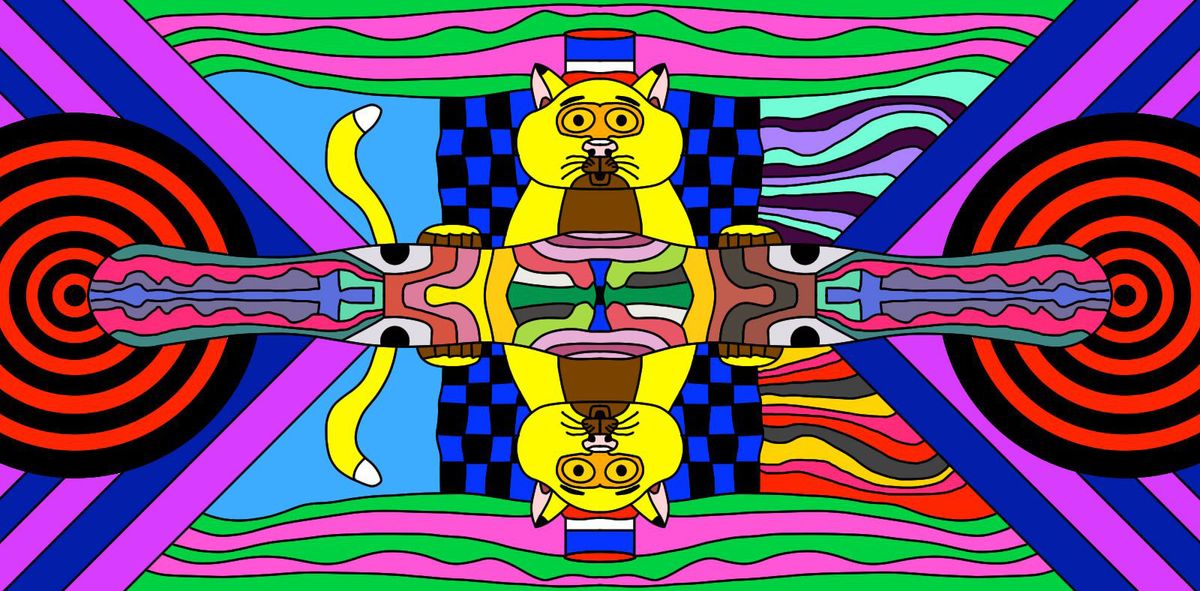

James Frye’s “Pussycat Self,” above, and “Being Himself,” below.

James Frye’s artwork packs in a lot to look at: vibrant colors and offbeat figures, psychedelic swirls, floating eyeballs.

To his parents, the titles are the most revealing part. “Personalities to Split.” “Blue Meanie’s Brains.” “Big Amoeba Nova.” To them, the carefully composed labels reveal James’ interests and his thinking – often mysterious in a 21-year-old with autism, who didn’t talk until he was 8, who still has trouble answering questions that start with who, what, why, when.

Sitting at her kitchen table last week in Spokane Valley, as her family prepared for James’ First Friday debut, Wendy Frye laughed and said it’s unlikely her son ever would make it as a “sandwich artist.” And she expects he’ll always live at home. But what she and her husband, Dan Frye, have learned from James’ artwork: He’s a deep thinker. And, in his mind, he’s an artist’s artist.

Others are taking note, in the disability community and the mainstream art world. Frye’s work hung recently at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle in a show of artists with autism. It was featured online in July in a mainstream juried show run by Upstream People, and it’s hung at the Kress Gallery at River Park Square and elsewhere in Spokane.

Frye will show his work tonight, as part of First Friday, at Express Employment Professionals.

Frye transfers his drawings from an electronic tablet to his computer to add color, bold choices that saturate the canvases they’re eventually printed on. Dan Frye said he asked James once how he chose his colors. He hears them, James replied. He has synesthesia, which means one sense, such as hearing, is perceived as if by another, such as sight.

Frye is influenced especially by popular music from the 1960s and ’70s, but in one sitting he might also play Christmas music, the Sex Pistols and Ray Charles.

His art offers a glimpse into how he interprets music, and the rest of the world.

“That’s what parents and society and doctors want to know: What are you thinking? How does this work for you?” Wendy Frye added. “And without that ability to write or articulate what it is really like … it’s – it’s been really refreshing.”

Frye’s “Being Himself” shows a man whose skull gapes open, allowing a swirl to escape filled with color and shape. In “Holding Still,” a stooped, deflated-looking man stands on a pedestal.

His interest in art started at Central Valley High School, where he took a pottery class and consumed his teacher’s collection of art history books. His knowledge of artists – their media, styles, biographies – is extensive, his parents said.

Last week, his dad asked James, ensconced at his workstation in a den in his parents’ basement, to demonstrate the stylus he uses to draw. He explained instead: “Right hand, and straight lines and curvy lines … come to you.”

Before he started making art, her son was an angrier person, Wendy Frye said. He’s gained confidence, she believes, and he feels more understood. He initiates conversations now: “He’s found a sense of self.”