Surviving a bad break: Free helicopter service saves backcountry skier injured in avalanche

(MOLLY QUINN mollyq@spokesman.com)

Yet the ordeal came down to a free helicopter rescue service and a gutsy pilot – after dark with just minutes to spare in a blinding snowstorm – to make the ultimate difference between life and death.

“No skiing is worth this type of injury,” said avalanche survivor Mike Brede at his Spokane home last week after surgery, 10 days of hospitalization and nearly a week of treatment at St. Luke’s Rehabilitation Institute. Complete recovery is a challenging year away, he said.

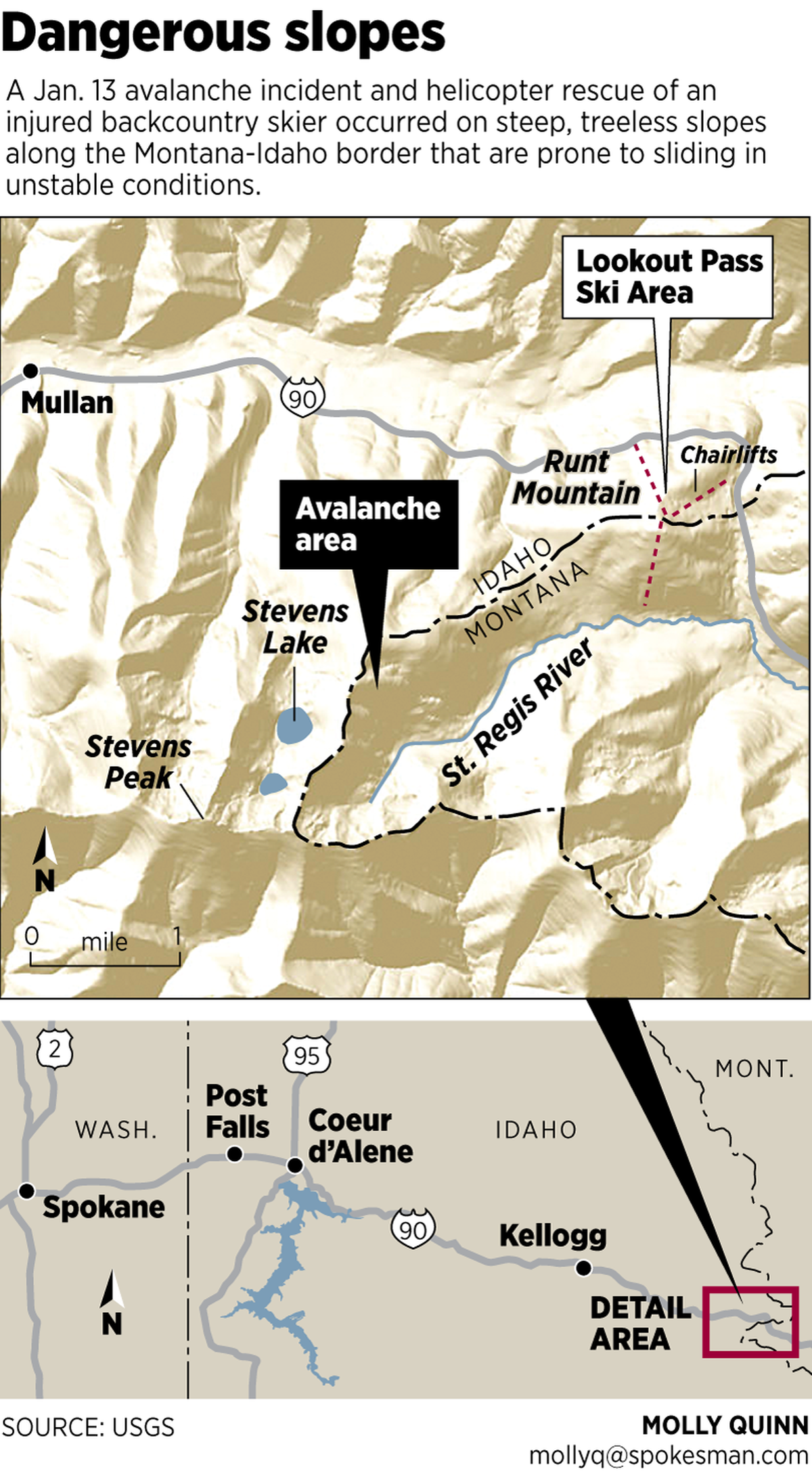

Brede, 31, and Brandon Byquist, 35, were on backcountry skis on Jan. 13 and Jason Hershey, 41, was on a splitboard when they left the boundaries of Lookout Pass Ski Area and headed south along the Montana-Idaho border.

That was the plan: Make a few runs in the ski area and leave around 10 a.m. if conditions were favorable.

“That would give us enough time to make a good backcountry run and ski back (in the St. Regis Basin) to catch the last ride up the east-side lift before the resort closed that afternoon,” Brede said.

He’d left a map with a planned route on his computer screen at home for his wife to view if needed.

Conditions seemed good as they attached skins on their skis to climb and trek for more than two hours. All three men have years of backcountry experience. Brede learned to ski at age 3. They’ve all had avalanche awareness and Wilderness First Responder or advanced medical training.

They were carrying iPhones, avalanche transceivers, probes and shovels plus extra food, water and clothing.

Brede also had a GPS device and an ACR personal satellite emergency locator.

“We did a few shovel tests along the way and the snow seemed fine,” he said, noting that after more than two hours of traveling, they began angling for downhill lines.

“Our protocol calls for skiing one at a time and stopping at safe zones to reevaluate as we move down.

“We were coming to a decision point,” Brede said, noting they had talked about the slope as being questionable. “When we broke out of the trees there was some wind, but not a lot. I was leading at that point and I went for it.”

Brede had skied the area several times previously.

“The slope angle was steepening in the open area,” Hershey said. “Brandon and I were still in the trees and just getting to the point of stopping and raising the question of whether we should continue or skin up and head back to safer terrain.

“Mike was farther ahead of us. He was leading out under a rock outcropping and we heard a boom in the bowl and felt shockwaves under the whole snow pack.”

“The slope had changed a little,” Brede said. “I made a couple of turns and fractured a wind slab about 6 inches deep. I thought I could traverse out of trouble and get to a safe zone, but then a deeper layer cut loose and took me down.”

The preliminary report by the Idaho Panhandle Avalanche Center says Brede was about 100 feet from the top of the ridge when he triggered a wind slab that stepped down to a layer 30 inches deep and 300-500 feet wide.

Hershey said it was “numbing” to watch the torrent of snow sweep Brede over a hump and out of sight. “We didn’t know about Mike or if we were going to be next,” he said.

“Brandon was yelling ‘Pull your air bag! Pull your air bag!’” Brede said. “So much was going on, it’s hard to say what got me to pull the cord.”

Brede was wearing a helmet and a pack equipped with an ABS Vario Air Bag, a $1,000 item he reviewed this winter in Out There Monthly.

“If everything else goes wrong and you find yourself caught in an avalanche, an airbag is designed to keep you at the surface of the snow and visible to rescuers,” he wrote.

Brede said he’s been using the ABS Vario airbag system for several seasons. Admitting that he’s cringed at the extra weight at times, “my ABS pack goes with me every trip.”

It paid off.

Everyone involved in the incident, from the skiers to avalanche investigators believe the airbag kept Brede from being buried.

“I’d never deployed the bag previously, but I’d practiced the motion of reaching to my chest and pulling,” he said. “I’d read that only 20 percent of people wearing an air bag pull the cord when involved in an avalanche.”

Swept off his skis with the airbag deployed, the rampaging snow dragged Brede off a ridge and into an open bowl studded with rock outcroppings.

“I felt a free fall and then immense pain in my leg,” he said.

“When I came to rest I was buried up to my bellybutton and then snow kept coming and filled in up to my chest.

“I held one arm up in the air; that’s what you do. Luckily, my air bag kept me above the surface almost the entire time. I came to rest sitting, facing uphill.

After the snow stopped moving, Hershey and Byquist responded by yelling to Brede and descending. “We had to ski down into a place we didn’t want to go into, but we had a friend who needed help,” Hershey said.

“We were triggering little slabs. When we saw Mike’s arm waving, it was at least a relief to know we wouldn’t be doing a beacon search.”

Brede’s lower leg injury was immediately obvious with the bleeding muscle filleted back to expose his tibia and fibula.

“We had complete first-aid kits and they applied QuikClot to stop the bleeding, and braced it with ski poles and straps,” Brede said.

But they didn’t know about the broken pelvis, and Hershey was digging snow away from Brede’s torso when he discovered the worst of the situation.

“Blood was pooling under his butt,” Hershey said. “That’s when we saw he had bone exposed: compound fracture of the femur. I have enough training to know that he’d bleed out quickly if we caused damage to his femoral artery. We could not move him to a safer place.”

Suddenly their hopes were slipping from stabilization and self reliance to the urgent need for assistance.

“We could have used more QuikClot,” Byquist said.

At 2:25 p.m., the group’s first 911 call was received by Shoshone County Sheriff’s dispatchers. At 2:47 p.m., Shoshone County notified Mineral County Sheriff because the avalanche was on the Montana side of the ridge.

Brede’s emergency beacon wasn’t deployed until 3:01 p.m.

“In the beginning, we were calling family members and 911 and trying to get a coordinated effort going,” Brede said.

“Being on the Idaho-Montana border, there were so many agencies involved. It seemed to be a logistical nightmare for everybody.”

To make things worse, the skiers noticed their iPhone batteries were dying quickly, possibly from a combination of the cold, poor connection and signal searching.

“We were lucky to get any calls out of there,” Brede said.

Dispatchers asked several times for coordinates off their iPhones instead of the GPS, which was giving a funky reading. “They said the GPS coordinates were indicating we were in Canada,” Brede said.

They assessed their options. Ground crews likely couldn’t get to the accident site safely. A helicopter couldn’t land on the steep slope. Weather was deteriorating. Darkness was fast approaching.

Said Byquist, “Mike is so knowledgeable. He knew the only formally equipped rescue helicopter that might be available to us in that situation was Two Bear Air. I’d never heard of them.”

They tried to relay the Two Bear information but got no assurance from Shoshone County dispatchers handling the 911 calls in Wallace, Idaho.

Activation of the emergency satellite locator mayday signal was the key that launched the helicopter service, said Deputy A.J. Allard, Search and Rescue liaison for the Mineral County Sheriff in Superior, Montana.

“That signal is for an urgent situation and we react accordingly,” he said. “We notified Two Bear Air, which has helped us several times. They’re a very, very handy asset in this sort of rescue.”

Based in Whitefish, Montana, Two Bear Air is financed by philanthropist Mike Goguen, who put up $10 million for two rescue helicopters and funds the training, maintenance and operation costs for search and rescue missions.

“I’m on call 24/7,” pilot Jim Bob Pierce said last week. “We’re not an air ambulance, but our crew can assemble and launch in about 40 minutes.”

In addition to calling in the helicopter service, search and rescue teams on both sides of the state line were dispatched, Allard said.

But the skiers on the avalanche slope didn’t know whether any rescue was coming – and nobody knew if rescue was possible.

“After the accident, the weather deteriorated like crazy,” Byquist said. “We estimated the snowfall rate was 2 inches per hour.”

Before 4 p.m., the skiers had just enough phone juice to get a call advising them that Two Bear was responding but couldn’t guarantee the chopper could get to the site.

“I was trying to stay conscious; trying to stay warm,” Brede said. “Brandon and Jason gave me all of their down layers, gloves and mittens. The air bag helped make me more comfortable, but I was still getting cold.”

Meanwhile, the Two Bear pilot, joined by a paramedic, was drawing from 4,800 hours of flight time and more than 2,000 hoist missions just to reach the area.

“We venture out and see what we can see once we get there,” Pierce said.

“I knew the weather was bad and that nobody else would fly on these guys,” the pilot continued. “It’s not that we’re cowboys or anything like that, but we don’t have the three-miles and 3,000 feet rules the air ambulances and the like have for visibility.

“If we waited for that, hardly anybody would get rescued.”

Instead of a direct flight from Whitefish to Lookout Pass, Pierce had to wander south through valleys and canyons until he could follow Interstate 90.

“We were flying low level all the way,” he said.

The 3-hour wait was emotionally agonizing, Hershey said.

“There was a period when we had to remain positive even though we were doubting whether a helicopter was coming,” he said. “We might be sitting there all night in a live avalanche zone watching our friend die.

“Mike was alert, but at one point he said, ‘I’m going down fast.’ He was getting less responsive. He wasn’t complaining about the the pain or the cold anymore. That’s when it looked bad.”

Hershey believes Brede, who was beyond the shivering point of hypothermia and still bleeding, was within a few hours of dying when they heard the helicopter.

“We got to the victim right at dark, flying under night vision,” Pierce said. “It was snowing really hard.”

As the chopper hovered and fanned the new snow into a blizzard, the paramedic descended on the cable.

“He told me it was too dangerous and there was no time for me to be stabilized and strapped on a litter,” Brede recalled.

“We had to take him out in what we call the Screamer Suit,” Pierce said. “It’s a coat with a strap that comes between his legs and works like a little hammock. He and the rescue specialist came up together.

“There was no time to spare. He was in very, very poor shape and they were still in the middle of the avalanche zone. It wasn’t a safe place to be.”

Brede said he was more than ready: “The rescuer told me to prepare myself for the worst effing pain of my life,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Let’s do this.’ ”

“Mike’s eyes rolled back in his head when the cable tightened,” Hershey said. “It must have been the worst pain imaginable.”

“They brought me up into the helicopter and I flopped on the floor,” Brede said. “Minutes later they were loading me into an ambulance at Lookout Pass.”

The injured skier would be in surgery in three hours and getting refilled with six units of blood.

“In a 1,000 hours in this helicopter, this is the first time we had blood everywhere,” Pierce said. “It looked like we’d gutted a deer in the helicopter.”

But the ordeal wasn’t over.

Two Bear quickly flew back to pluck another skier from danger.

“They came in a blizzard in darkness,” Hershey said. “All the bumpy avalanche debris around was completely covered smooth by new wind-blown snow.

“We were concerned that the slope was loading for another avalanche.

“I was terrified that the chopper would trigger more slides.”

Equipped to take only one additional person at a time, the heli-crew hoisted Hershey aboard and flew him back to Lookout Pass.

“The chopper was stirring up so much snow, I had to hunker down in a little ball,” Byquist said. “The rescuer looked at me with a stone face and said, ‘We’ll come back for you if we can.’

“They were there and gone in 90 seconds.

“That’s when it struck me that I’d been left in a snowstorm wearing only a polypropylene base layer and a shell jacket. Everything else was wrapped around Mike.

“And I was soaked from all the adrenaline rush and the snowfall.”

Byquist heard the helicopter 20 minutes later. And then he didn’t.

Two Bear was able to get three quarters of the way back to the accident site before turning back. “Visibility was just down to nothing,” Pierce said. “We had to turn it over to ground rescue.”

“That’s when I thought, ‘Omygosh, this isn’t happening,’ ” Byquist said.

His options were limited. Staying put was too dangerous, so was going back up to the ridge.

“My only choice was to get down into the St. Regis Basin and ski out,” he said, noting that he was still in mid-slope.

“I had my skis on my back,” he said. “I was too rattled to try skiing. It was dark. I had about 10 feet of visibility in the snowfall with my headlamp. I felt there was less risk of triggering another avalanche by being off my skis.

“I was treading very lightly; made a couple hundred vertical feet of descent to a couple of small trees. I grabbed one tree and gingerly stepped down from it when the entire slope below me broke loose and avalanched.

“If I’d have taken one more step without a hold on that tree I would have gone down for the ride.” Alone.

Pausing to calm down and collect himself he realized the avalanche was his ticket.

“That slide cleared the slope. I got on my back and glissaded down near the bottom.”

He clicked into his skis and felt reassured as the exertion started flowing warmth back into his body.

“At that point, I was good,” he said. “I knew I just had to keep the St. Regis River on my right side and continue out of the basin until I hit the snowmobile trails and made it out about four miles to Lookout Pass.”

He wasn’t out of the woods. “I floundered at times breaking trail in all the new snow and had to backtrack out of several thick stands of trees before I saw lights up ahead.”

After a mile of grunt work, he saw a search and rescue team’s headlamps. “They said they had been shooting guns and making noise with chainsaws to help me know they were in the area,” Byquist said, “but I hadn’t heard a thing.”

Byquist was in good hands and, after a quick medical check, they had him on his way out in a side-by-side tracked vehicle, arriving at Lookout Pass Ski Area parking lot at 8 p.m. “At that point, my only concern was Mike,” he said

Brede was hesitant to be interviewed about the ordeal, but he was eager to reveal details that might help other backcountry travelers learn from his experience.

“I’m really thankful for everyone out there who played a part in rescuing me,” he said. “I can’t express enough thanks.”

He already had helped organize an online community called PanhandleBackcountry.com to share backcountry travel information largely focused on winter skiing and riding with an emphasis on safety.

“Hindsight is always closer to 20-20,” he said. “Going into the accident was a very fluid moment. There weren’t many red flags. Although it started snowing and warming in the two hours when we were skiing into the area, it was a wind slab that got me. We hadn’t encountered it earlier because we’d been in the trees.”

Brede said he survived with an elevated sense of the inherent risk and need to be aware of surroundings as he skis.

“Groups should stop occasionally so everyone gets input on route decisions, and everybody should be educated enough to give educated input. If there’s any doubt, ski out another line or go back.”

“This only emphasizes to me that we have to be vigilant at all times about training more,” Byquist said.

“Maybe we let our guard down just a little bit because everything had been so stable,” Byquist said, noting that skiers should never stop learning. “We had a solid month of excellent snow stability in the backcountry. There was no ignorance in our group, but you always have to work at not letting complacency leak in.”

Kevin Davis of the Idaho Panhandle Avalanche Center, who said a full report of the accident has not been completed, credits the three skiers for their preparedness with training, trip planning and proper gear. “They needed all of that to have a good outcome,” he said. “A lot of skiers and snowmobilers aren’t so prepared.”

“That’s our standard protocol, whether it’s a short day out from the lifts at Lookout Pass or a 15 miler,” Byquist said. “I would be willing to carry even more knowing what I know now.

“All the bits and pieces of how we prepare added up to getting out of there in time for Mike to stay alive.”