A dad celebrates finding lessons where he least expects them

I made an arrangement with my 6-year-old son earlier this spring that seemed to benefit both of us. I’d pay him a penny for every stick he collected from our backyard, and he’d earn enough money to buy a few pieces of candy. As a bonus, outsourcing the work to him would spare my back from the pain brought on by constant bending.

But 10 minutes into what should have been a simple job, I glanced out my kitchen window and noticed that instead of placing the sticks in the paper lawn bag I’d left him, my son, Dean, was lining them up in some kind of intricate pattern near the swing set.

I stood by the window, puzzled, and watched him for a few seconds before calling outside.

“Son,” I said, “I’m not paying you to play with the sticks. Get to work.”

A few minutes later, Dean burst into the kitchen and yanked frantically on a drawer where we keep paper and pens.

“Son, there aren’t any sticks in this kitchen,” I said.

He told me that he’d changed his mind about cleaning up the backyard. He was going to build a fort instead. He was searching, he told me, for paper and a pen to plot the steps for his construction project.

I tried to hide my frustration, but a tiny part of me was annoyed that, yet again, one of our children had found a way to get out of a chore that began as nonnegotiable.

Over the next several hours, I watched from a distance as my middle child repeatedly lined up scraggly sticks in an attempt to build his prized fort, only to have them come crashing down around his feet.

I convinced myself that he’d eventually get bored, and then I could insist he get back to work. But a pattern quickly developed. He’d hypothesize, carry out an action and then record his findings on the paper. I realized that rather than defying me, my son was conducting a science experiment.

And we weren’t the only ones paying attention to Dean’s adventures in our backyard.

A post my wife wrote on Facebook drew 54 responses and more than 125 emoji responses. Many commenters encouraged Dean’s project, while a few offered to connect him to friends who were engineers, or at least familiar with a hammer.

“For those of you following the Dean-wants-to-build-a-fort story line, apparently sticks won’t work, but our hero plans to keep trying! Viewers, stay tuned,” my wife wrote.

Later that night, after we’d put the children to bed, my wife, still impressed by Dean’s determination, made a suggestion that seemed almost comical to me. What if I helped him build a fort, she asked? I raised an eyebrow and shot her a look that said, “you’re not married to the handy type.” After a good laugh, we moved on to a different topic.

As I drifted off to sleep, though, I couldn’t shake the image of my son in the backyard, determined to succeed and convinced that his best effort could result in something worthwhile.

The next morning, I was still thinking about my wife’s suggestion. With the children out of earshot, I told her about my plans to help Dean, and watched as her face settled into an “oh, honey you were right, I didn’t marry the handy type” expression.

We agreed that we wouldn’t share our plans with the children until we were on our way to the hardware store. No sense building up their hopes prematurely. That weekend, as we drove to the store, I informed them that we were going to buy supplies to build a fort in the backyard. They danced in their seats and talked about the materials we’d need.

At the store, we made our way to the lumber aisle. I stood in front of a stack of 2-by-4s for what must have felt like too long to a 5-year-old, because my daughter walked to a nearby pallet of wood and said “maybe we can use these sticks, daddy.”

I gave myself a silent pep talk and took my cart full of wood, nails and a few other items to the checkout.

Back home, the children were so excited that they insisted on dragging the 8-foot-long pieces of wood up the hill in our backyard. These were the same children who scream in protest anytime we ask them to carry a loaf of bread inside after a trip to the grocery store.

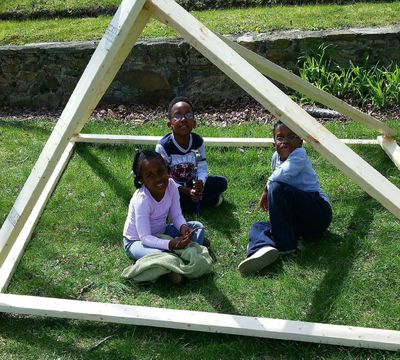

We put our heads together and, over the course of a couple of hours, turned the pieces of wood into a structure that, while more teepee than fort, represented our collective best effort. After the frame was complete, the children helped me staple a tarp on as the roof. They smiled as we stood and admired what my oldest son declared “the best fort in the world.”

The fort has inspired my children to spend more time outside, plotting all kinds of mischief and mayhem. And our best effort, in this case, yielded much that was worthwhile: inspired outdoor play, time together and a sense of accomplishment. In the process, I learned that some of life’s best lessons happen when you least expect them.

Davis is deputy chief of staff and communications director for the president of the Baltimore City Council.