Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize sparks lively – and at times snobby – conversations on the aesthetics of music

If a sampling of some classical music aesthetes on social media is to be believed, April 16 marked the day the music died.

A rapper – a rapper! – named Kendrick Lamar was placed on a pedestal as the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize in music, joining geniuses of American composition including Aaron Copland, George Crumb, Elliott Carter and dozens of other classically trained artists. Lamar, 30, did so without studying in a conservatory, mastering an acoustic instrument – other than his vocal cords-or composing a single opera.

“As if pop doesn’t have enough awards already,” groused one Facebook commenter in a post-announcement conversation started by Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic, USC professor and former Pulitzer juror Tim Page.

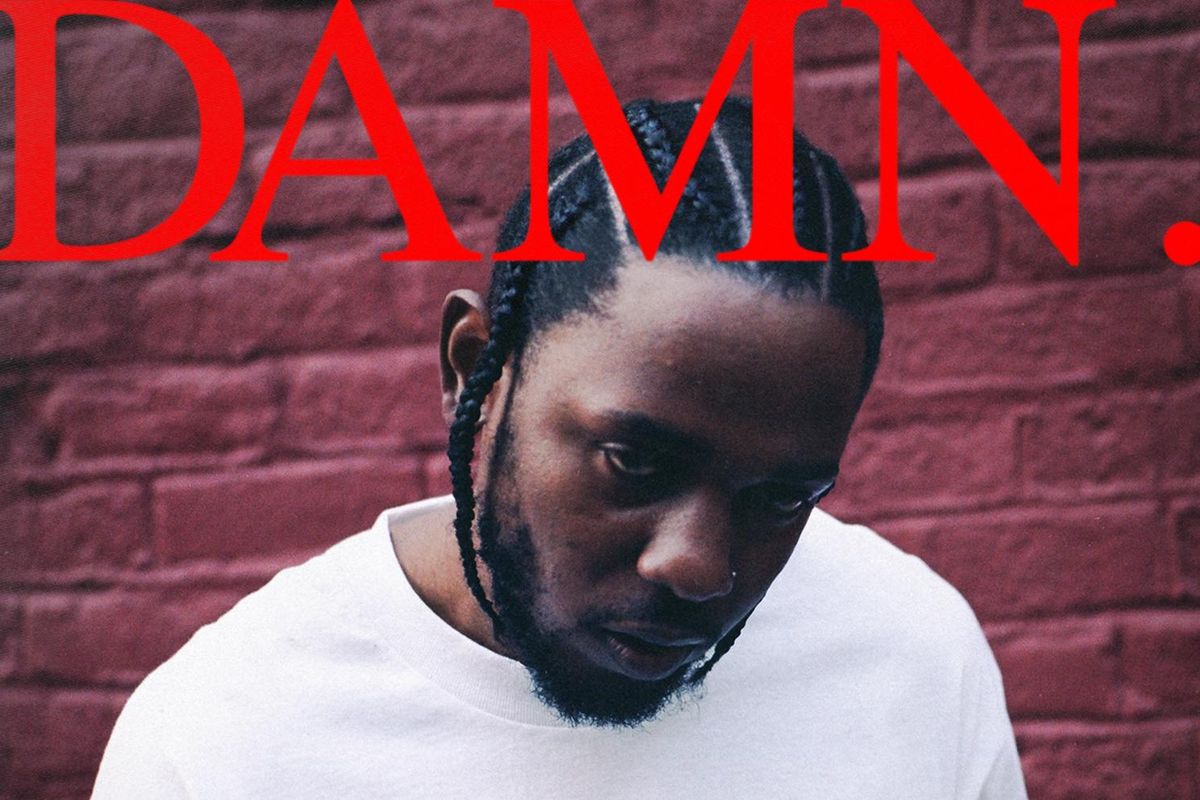

Another detractor replied that, despite first thinking that the news was written for parody site the Onion, he decided to give Lamar’s “Damn” a chance. His verdict: “It’s incoherent, nasal yakking over a migraine inducing throb. The Pulitzer has lost all meaning.”

Yet social media are ground zero for griping, and plenty more, however, applauded the decision by Pulitzer jurors to acknowledge what is the dominant musical art form today in America. In 2017, the combined genres of R&B and hip-hop proved to be the most consumed music in the U.S. for the first time in history, according to Nielsen Music.

Ultimately, this year’s prize for music has sparked a vibrant conversation about aesthetics, class, the division between so-called high and low art and whether giving one of the most esteemed prizes in American music to one of its most popular musicians represents a long-overdue corrective or an insult to non-commercial, so-called serious music.

“I wouldn’t describe it as a shift,” said Dana Canedy, the new administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, when asked how she thinks this will affect the music prize going forward. “I think that is a big moment for both hip-hop and for the Pulitzer Prizes, one that we’re very proud of.”

She added: “Obviously this is not a genre we’ve seen celebrated before, so that in that sense it’s historical, and we’re glad to have made that happen.” Canedy hopes that the move “sheds a whole different light on hip-hop.”

For his part, Page, former classical music critic for the New York Times and the Washington Post who is now a professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, sparked his online conversation when he wryly noted that there was outrage over Lamar’s achievement among some friends.

“Maybe I’m just getting old, but I don’t believe that any single prize will bring on the Decline of the West or that the choice of a genre necessarily limits the brilliance that a composer can bring to it,” he wrote in a post, which he has given The Times permission to publish.

The responses included enthusiasm, skepticism and hostility. One even suggested that Lamar likely didn’t care about the win. Nonsense, replied others. (Lamar, as of press time, has yet to give a statement or an interview about the Pulitzer.)

Writer and 2018 Pulitzer music juror David Hajdu was with his four fellow jurors as they discussed whether Lamar’s album should be given the prize. He said that he was encouraged by the jury’s decision to honor “Damn.”

Noting that the award “is not a prize for the best classical music or the best jazz-it’s a prize for the best music,” Hajdu said that genre or style isn’t considered as part of the process. “It’s a prize for achievement in music, and there is high-level achievements in music across forms and across styles.”

Added Hajdu: “To the degree that this is a corrective, I think it’s a positive one.”

The Pulitzer Prize in music has long struggled to define what work it considers worthy of consideration. It first awarded a non-classical artist in 1997 when jazz trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis won for his work “Blood on the Fields.” A decade later jazz composer Ornette Coleman won, as did avant-garde jazz composer Henry Threadgill in 2016.

But popular music has mostly been ignored, aside from the Pulitzers retroactively recognizing what Hajdu described as “disreputable forms and popular forms” including Hank Williams and Bob Dylan.

The Pulitzers have certainly experienced growing pains over the decades. Most famously, in 1965, the Pulitzer advisory board nixed the recommendation of a jury that had pushed for Duke Ellington to be given a special citation for the “vitality and originality of his total production.”

According to a Times article at the time, “Ellington responded to the slight in his usual aristocratic fashion offering the comment, ‘Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn’t want me to be famous too young.’ He was 66 at the time and died in 1974.

Hajdu said he hopes Lamar’s honor marks a turn. ”To the degree that this might open the door to consider the quality of contemporary country music, or for that matter contemporary rock or contemporary pop, I think that’s great.

“It is not a lifetime achievement award and it’s not an award for body of work,” he added. “It’s an award for high achievement in new works.”

One Lamar defender in Page’s conversation was the writer and physician Jeremy Faust, who serves as the board president for vocal group Roomful of Teeth. The group premiered composer Caroline Shaw’s Pulitzer-winning piece, “Partita for 8 Voices.”

“Nothing here has changed,” Faust keenly observed of Lamar’s Pulitzer. Using classical composition jargon, he noted: “It’s just that when Kendrick sprechstimmes in small pitch class cells, over minimalism background, people call that rap.”