‘Modern-day medicine people:’ Students get hands-on experience at Na-ha-shnee Health Sciences Institute

Nina Card was not doing well.

“I’m having a hard time breathing,” she said, as five high school students surrounded her bed.

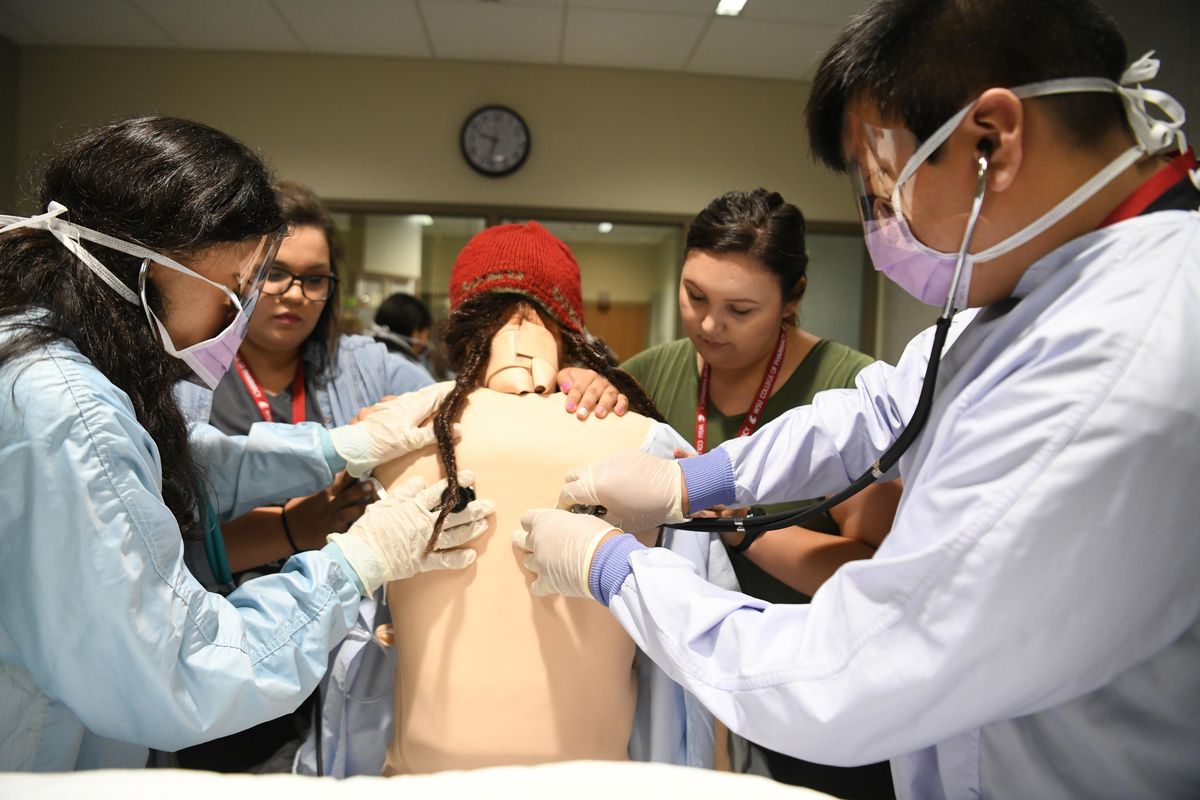

Under the guidance of Terrin Utter, a senior at Washington State University’s College of Nursing, the students measured Card’s blood oxygen saturation and hooked her up to a cannula to get more oxygen flowing into her lungs. The beeping monitor in the room showed her saturation levels improving as students increased the flow of oxygen.

Card is not, strictly speaking, a person: She’s a hyper-realistic mannequin at Washington State University’s College of Nursing Simulation Lab, voiced by one of the lab directors.

Typically, the lab is used so nurses in training can practice clinical care on realistic patients. But this week’s lab was a little different. It was part of the Na-ha-shnee Health Sciences Institute, a fusion of summer camp and in-depth health education for Native American high school students.

“It was very realistic. A little creepy,” said Tyee Rigdon, a Yakama Nation teenager who wants to be a pediatric nurse.

Na-ha-shnee is an 11-day educational workshop in which students learn everything from pharmacy compounding to basic dental health care on the WSU campus, while staying in dorms at Gonzaga University.

Many of the counselors, like Utter, are native and work in health fields.

The program blends cultural activities, like making baskets and learning Salish, with hands-on lab time.

For Emma Noyes, the camp’s director, the two are deeply intertwined.

Noyes is WSU’s director of Native American health sciences and has a background in public health work. She told Na-ha-shnee students that she went into health care because of an experience her cousin had going to a hospital in Omak with severe abdominal pain during the Omak Stampede, a large intertribal event.

Noyes said her cousin was doubled over and vomiting repeatedly. The nurse in charge of triage in the emergency room tried to get him to leave and told her uncle, “We’re not going to have a drunk Indian throw up all over our waiting room.”

“That nurse would not see him, would not take him back,” she said. Her uncle persisted, and her cousin was rushed into surgery for appendicitis after another nurse correctly diagnosed him.

“Stories help us find purpose,” she said.

When applying to the camp, students write a personal statement about why they want to become “modern-day medicine people,” as Noyes calls them. Many speak of wanting to give back to their communities or share personal stories about wanting to help cure diseases that have affected loved ones: cancer, diabetes, drug and alcohol abuse.

Tuesday was the second day of the institute, and the first with hands-on lab sessions. In teams, students were expected to care for the mannequin based on a file of doctor’s instructions, including managing postsurgical pain, bringing her a meal and monitoring breathing.

Half the group watched from an adjacent observation room and made notes on how their peers could improve: Ask the patient how she’s doing right away, take steps to control her pain and check her lung sounds more quickly.

At the end, lab director Kevin Stevens and senior instructor Laura Wintersteen went over the exercise, walking through the choices each group made, and said the high school students performed as well as new nursing students.

“Nursing is not about just doing things,” Stevens said, calling attention to places where students checked a symptom or vital sign, made a treatment decision and then reassessed the sign to check for improvement. “All of that is the nursing process.”

Rigdon, the Yakama student, said she’s always wanted to work with children and recently decided she prefers pediatric nursing over being a teacher. Her mother found out about Na-ha-shnee from a friend.

“I was really nervous at first,” she said of the simulation. “It’s strange because it’s not a real person, but you want to do well.”

Because she’s going to be a high school senior in the fall, she won’t be eligible to return to camp next year. Though she is only two days in, she already would like to come back.

“I really like it,” she said.

Noyes said Na-ha-shnee has been able to incorporate more hands-on medical training now that WSU’s Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine is operating. This year, she’s especially excited about a lecture from Dr. Terry Maresca of the Seattle Indian Health Board on integrating traditional medicine, like plant remedies, with Western practices.

Roland Wilson, a returning student who’s part of the Nez Perce tribe, said he wants to be a neurosurgeon and came back because he had such a good time last summer.

“Living in Pullman, the only natives were me, my brother and one other person,” he said. Last year, he was able to learn about other tribal traditions in addition to the medical training.

Wilson said he likes brains and working with his hands, doing fine detail work like painting or cooking. But his favorite part of Na-ha-shnee was anatomy lab, where students get to look at various organs from actual bodies. This year, Wilson had no trouble picking what he’s most looking forward to.

“Cadaver lab, round two!” he said.