When LBJ dissed Tom Foley among stories that could be highlighted in documentary promoting civility

On the stump or the chicken dinner circuit, Congressman Tom Foley rarely started a speech without first telling a story.

Some had a deeper meaning about politics, policy or life in general. Others were just amusing icebreakers, but if someone was the butt of the joke or the person learning the lesson, it was always Foley himself.

How he was once paged at National Airport by the White House for a call from President Lyndon Johnson, was sent to a private room near the departure gate to take the call, only to have LBJ say “Foley? I told them I wanted Fogarty!” and slam down the phone.

How he reluctantly accepted an invitation to ride a horse in the parade at the start of the Omak stampede and lost his reins in front of hundreds of constituents.

How as a newly elected congressman, he and other new freshmen in an orientation session all leaned forward when a powerful committee chairman told them to beware the biggest mistake a new representative could make.

“He had a little bit of the Irish in his stories,” longtime friend Dennis Bracy said recently of the 15-term congressman who rose to be speaker of the House and served as ambassador to Japan after losing his re-election campaign in 1994. The stories were a little bit life lesson, a little bit civics lesson.

Years ago, when some friends gathered in Seattle for a reunion of those who worked for and with the late Sen. Warren G. Magnuson, it was clear Foley was the best storyteller of the bunch. Bracy, a former executive with Kaiser Aluminum in Spokane and now the chief executive officer of a film production company, got an idea.

Why not get Foley to sit down with a bunch of friends around a table, have him tell stories and just roll camera? In 2005, they did just that and wound up with some 5 1/2 hours of video.

Now there’s an effort to take some of that video – along with footage from his television appearances, speeches and perhaps clips from his 2013 memorial service attended by current and former congressional leaders and presidents – and turn it into a 60- to 90-minute documentary.

“We have lots and lots of footage,” Heather Foley, his widow, said. “Every time he was on a talk show, they’d send us a copy.”

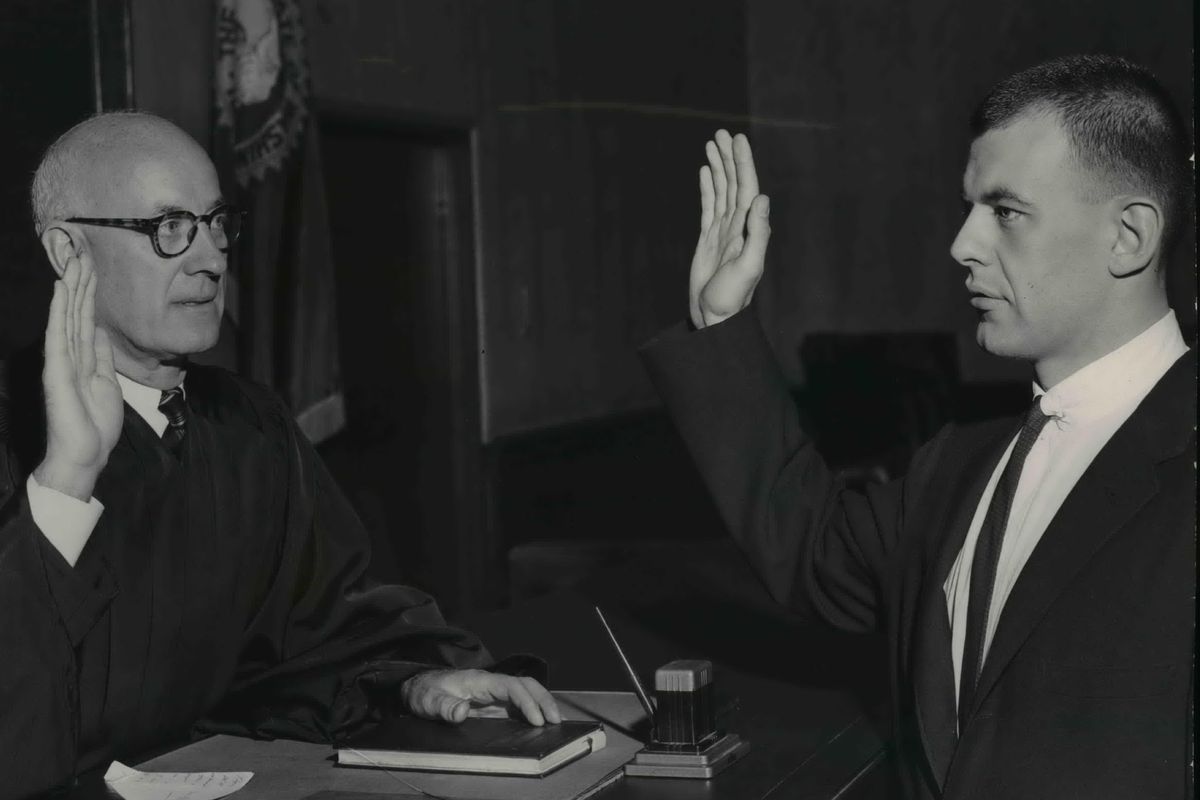

There were several cabinets full of video, along with a huge shoebox full of photos shot by his long-time assistant Janet Gilpatrick, that start in black and white and eventually graduate to color.

While the documentary would showcase Foley, it would be a bigger story about the way politics used to work – with civility, Bracy said.

“For a long time, nobody has seemed to know how to compromise,” Heather Foley said. The documentary would emphasize one of his main goals, she added, “the idea that we all work together for the common good.”

It would also have some lessons that resonate with today’s headlines, Bracy said, such as the clip of former President Bill Clinton speaking at Foley’s memorial service at the U.S. Capitol.

“He knew making the tough decisions was inevitable, and he paid the price,” Clinton said.

Clinton explained how he often took Foley’s advice after he was first elected, but not on one key issue, which he came to regret. When he pushed for an assault weapon ban in 1994, Foley warned “there would be blood on the floor of the House. Some of us will not survive.”

Clinton, believing the voters’ anger would pass quickly, convinced the House to add the assault weapon ban to an omnibus crime bill. Democrats, including Foley, voted for it. He and dozens of others lost their re-election bids, and Clinton faced a House controlled by Newt Gingrich and the Republicans.

There’s no shortage of material, Bracy said, and the production company could come up with documentaries of different lengths to meet the demands of different formats for different broadcast entities, like Public Television, the History Channel, Netflix or C-Span. What the project needs now is a director.

“I need a lower-priced Ken Burns willing to pull it together and make it work,” he said. “Someone with an outside view.”

Bracy, Heather Foley and the WSU Foundation recently held a fundraiser in Seattle, with some of Foley’s contemporaries in Congress from both parties, to raise money for the documentary, called “Tom Foley – Stories of a Lifetime.” Bracy hopes to have the documentary funded by the end of the year.

Along with the Foley Institute at WSU, they also want to develop a searchable video archive with the conversations, TV news stories, speeches and campaign commercials, an exhibit for the Library of Congress and fully edited stories available through a website and social media.

So about those Foley stories at the beginning of the article. Here’s the rest of them:

After LBJ slammed down the phone, Foley sat in that private office for a reasonable amount of time, then walked out. The airline ticket agent at the gate asked if he’d talked to the president. “Yes, I did,” he said, truthfully. The agent took his ticket and upgraded him to first class. “It was then I learned the power of the presidency,” he said. “Even a wrong number can get you upgraded.”

Foley had ridden into the rodeo arena with some expert riders who performed a series of tricks, then left while he struggled with his horse in the middle of the ring. “Well, you can see our good congressman is not wasting his time on riding lessons back in Washington, D.C.,” the announcer said over the loudspeaker.

He was embarrassed and angry he’d been talked into riding in the parade when he finally got out of the ring, but his aide said told him it was a good thing. The worst thing would be for some guy from the city to come to Omak and try to show off on a horse. And as long as Omak was in the 5th Congressional District, he always carried it in elections.

The young representatives all leaned forward, assuming it would be something like embezzling money from the office fund or having an affair with a staffer. “Thinking for yourself,” said the Democratic Campaign Committee Chairman Michael Kirwan.

It’s OK to have a strong opinion about some minor, parochial issue in your district, they were told. But on the big issues, trust the subcommittee chairman. Trust the committee chairman. Trust the whip. Trust the majority leader.

“And above all – Pray God! – trust the speaker. We find that representatives are sometimes elected by accident, but seldom re-elected by accident.”

The young members were a bit put off. They’d been elected to come to Washington to improve the country, and now they were being essentially told to sit down and be quiet for two years.

“In my years in Congress,” Foley would say, “I’ve been a subcommittee chairman, a committee chairman, the whip, the majority leader and the speaker. And the wise words of Michael Kirwan come back to me.”