Final score doesn’t measure effort on, off the field for Colton’s 8-man football team

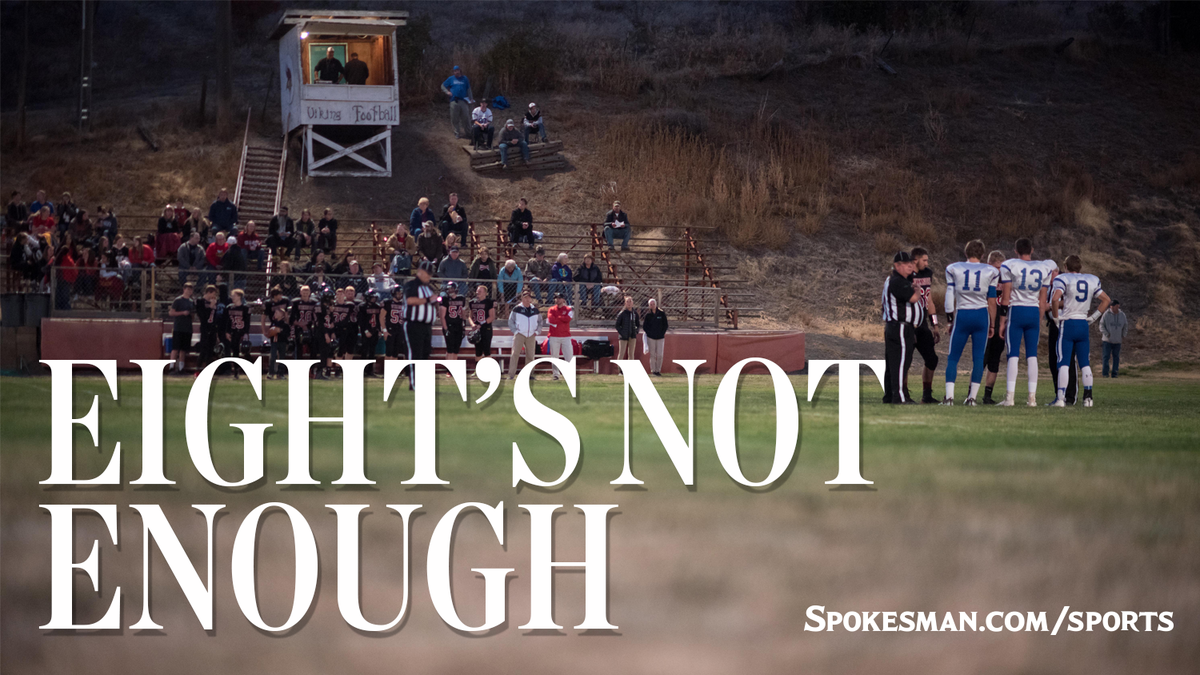

Action from the Colton vs. Garfield-Palouse high school football game on Nov. 1 in Colton. Garfield-Palouse won 52-44 (Luke Hollister / For The Spokesman-Review)

COLTON – Gusting wind and a sideways rain pummeled the players. It was about an hour before kickoff and the high school field was turning to a slippery, muddy bog.

“Let’s go, boys,” said Colton coach Clark Vining, standing at the 50-yard-line. “Get your head into it!”

The stadium lights were the only lights for miles when the 10 young men took the field. A lonely car whizzed by on U.S. Highway 395. Barns and factories and storefronts were dark. Everybody in this town of 467 people – it seemed – had gathered around the Colton High School football field for the Nov. 1 game.

Soon, the Colton Wildcats would battle their archrival, the Garfield-Palouse Vikings, in a game of 8-man football. Nothing more than bragging rights for the coming offseason were on the line, but hundreds had shown up to watch.

“Wildcat football – you can’t get any better than that,” said Parker Druffel, the team’s quarterback.

Behind the scene was a another story.

At small schools like Colton, football programs are at a crossroads. Dwindling rural populations coupled with declining participation rates have made this once-celebrated pastime an endangered game.

Concerns about injuries – especially concussions – have chased athletes from the football field, not just in rural Washington, but across the country. A study by the National Federation of State High School Associations indicates participation has declined across all high schools by 6.6 percent.

This year, 40 small high schools – ranging from Pateros in north-central Washington to Darrington in the northwest to southeastern farm schools like Pomeroy – played in the WIAA’s 1B classification, reserved for schools where enrollment cannot support an 11-man game.

Colton High had 10 players by the end of the season, the smallest weighing 89 pounds. That is roughly half the size of the team’s roster from a few years ago.

“Football, in general, it seems to be going in the wrong direction in terms of the number of athletes, and I’m not sure exactly why that is,” said Jim Moehrle, Colton’s athletic director and a former player and coach.

But in Colton, for now, the game lives on. It’s as much a community event as it is a football game. Colton residents park pickup trucks and cars near the end zone, huddle on the wet bleachers and stay long after the final horn.

“You come to a game Friday here, or any small town, it’s something that binds a community together,” Vining said. “They’re here obviously to watch a football game and cheer it on, but there’s more to it than that.”

Tough circumstances

but tight bonds

The survival of small-school programs often depends on the dedication of coaches like Vining.

After each game, the head coach will wash the dirt and grass stains out of each player’s uniform. Even if the Wildcats travel more than two hours to play, Vining will haul the laundry hamper back to his home and use his washer and dryer. Before practices, he drags out the blue tackling dummies for players.

“You look at some of those other programs and wonder if their head coach is dragging the bags out and washing the jerseys and doing all that stuff,” he said.

At the first practice three months ago, Vining only had 11 players. Soon, that number would dwindle to 10.

“We knew we had 11 guys going into the season,” Druffel said. “Everybody was like, ‘Oh, how are you guys going to get through the season? Some guys aren’t going to keep their grades up.’ Teammates fought hard for their grades and came out at practice every day and just really went at it. We were ready.”

Colton’s enrollment ranges from 40 to 50 students. The elementary and middle schools are situated inside the same building. Students know each other from kindergarten onward. Football participation numbers fluctuate on a year-to-year basis.

“We’ve had 16 to 20 kids throughout the years, and we knew we had a group coming with classes that didn’t have a lot of boys in them,” Vining said.

Vining knew this season would be one of the most challenging of his career. He’s known these kids since they first got involved with youth sports in the second grade. The team includes his son, senior Luke Vining.

“I can’t believe how fast it’s gone,” Vining said of coaching his son. “He was a manager for us in the first grade, grabbing the tee and whatnot. Time just flies by.”

The setting at Colton’s football field is modest. The field’s grandstands feature six rows of bleachers. The public address announcer and scorekeeper sit in lawn chairs underneath a folding tent. On the field, the white lettering on the team’s jerseys is splintered.

“You get a little jealous, but as a small school, you just have to realize that’s kind of how it is,” Druffel said. “Obviously, we don’t have enough money for everything we want, but we find ways around stuff.”

Triumph, heartache, all in one

It was Senior Night last week when Colton and Gar-Pal squared off. Earlier, Colton learned it had not qualified for the playoffs. This would be their last game together.

Druffel walked arm-in-arm across the field with his parents.

“Not gonna lie, I was definitely tearing up,” Druffel said. “Last game of them ever watching me in high school football.”

Then it was Luke Vining’s turn to take the field. As Luke met his mother, his father walked over and gave his son a hug. Though his son teared up and looked away, Clark Vining had the biggest smile of anyone in attendance.

At kickoff, old community traditions took center stage.

Choruses of “Let’s go, Blue!” filled the air. Car horns blasted each time the team scored. In 8-man football, the scores come quickly. In their first meeting, on Sept. 28, Gar-Pal outscored the Wildcats 90-56.

But the rematch would be different, the players vowed.

Timely defensive stops and long runs from Druffel helped Colton build a 30-14 lead midway through the third quarter. Gar-Pal mounted a fierce comeback, tying the game late in the third quarter.

“Line up on the 16!” Vining shouted. “They’re running out of the slot. You understand?”

Each player responded with an immediate, “Yes, sir.”

The Wildcats had the ball with 5 minutes left, tied at 44. Just enough time to mount one final scoring drive and steal a win.

On fourth down, deep in the red zone, Druffel threw toward an open Luke Vining in the right corner of the end zone.

But the pass sailed out of Vining’s reach. The ball sunk into the wet surface and a hush came over the stands. With the game tied, Gar-Pal had seized momentum.

Colton fans screamed for overtime – in a mix of hope and desperation.

With 7 seconds left, a Gar-Pal running back extended the ball over the goal line.

The crowd went silent, and Clark Vining sighed, looked away and removed his headset.

For Colton, it was the end of a season. Luke Vining fell to the turf as the final horn sounded. The crowd stood and cheered.

Time for celebration, tears

When a Colton game is over, a funny thing happens: No one leaves.

“Everyone just stands and talks and hangs out for a while, and then they finally turn the lights off and people go home,” Clark Vining said. “You’d hate to see something like that go away.”

The crowd of 200-plus fans takes time to greet each Wildcats players. It’s a time for pictures, hugs and stories.

This gathering was tough to swallow. The 10 Wildcats took a knee under the scoreboard, as the elementary-aged ball boys joined them. Parents formed a semicircle around the huddle as Vining approached.

The head coach’s voice cracked as he looked each player in the eye and delivered one final postgame message.

“I couldn’t be prouder of you guys,” Vining said. “I’ve coached a lot of you since the second grade. … We knew going into the season it was going to be tough.

“You had 10 guys for the second half of the season. I knew, every day, our 10 was going to be here, and that’s all you can ask for.”

It was the last time the group of 10 would take the field together. For some, like Druffel – who intends to walk on to University of Idaho’s football team – a bigger stage may be on the horizon. For others, 8-man football in rural Washington is as good as it will get.

As Vining broke down the huddle, the Wildcats rose and lifted their helmets together one final time. Vining took turns hugging each player. The longest of those was with his son.

When he got to his wife, Vining shook his head. Mom then turned to Luke.

“I’m so proud of you,” she said.

As players and fans slowly departed, a ball boy approached the senior wideout.

“Hey Luke, you’re my hero,” he said to Vining. “Can I have your autograph?”

Shortly thereafter, father and son retreated into the locker room. The last lingering fans departed. The stadium lights then shut off, leaving the field in almost complete darkness.