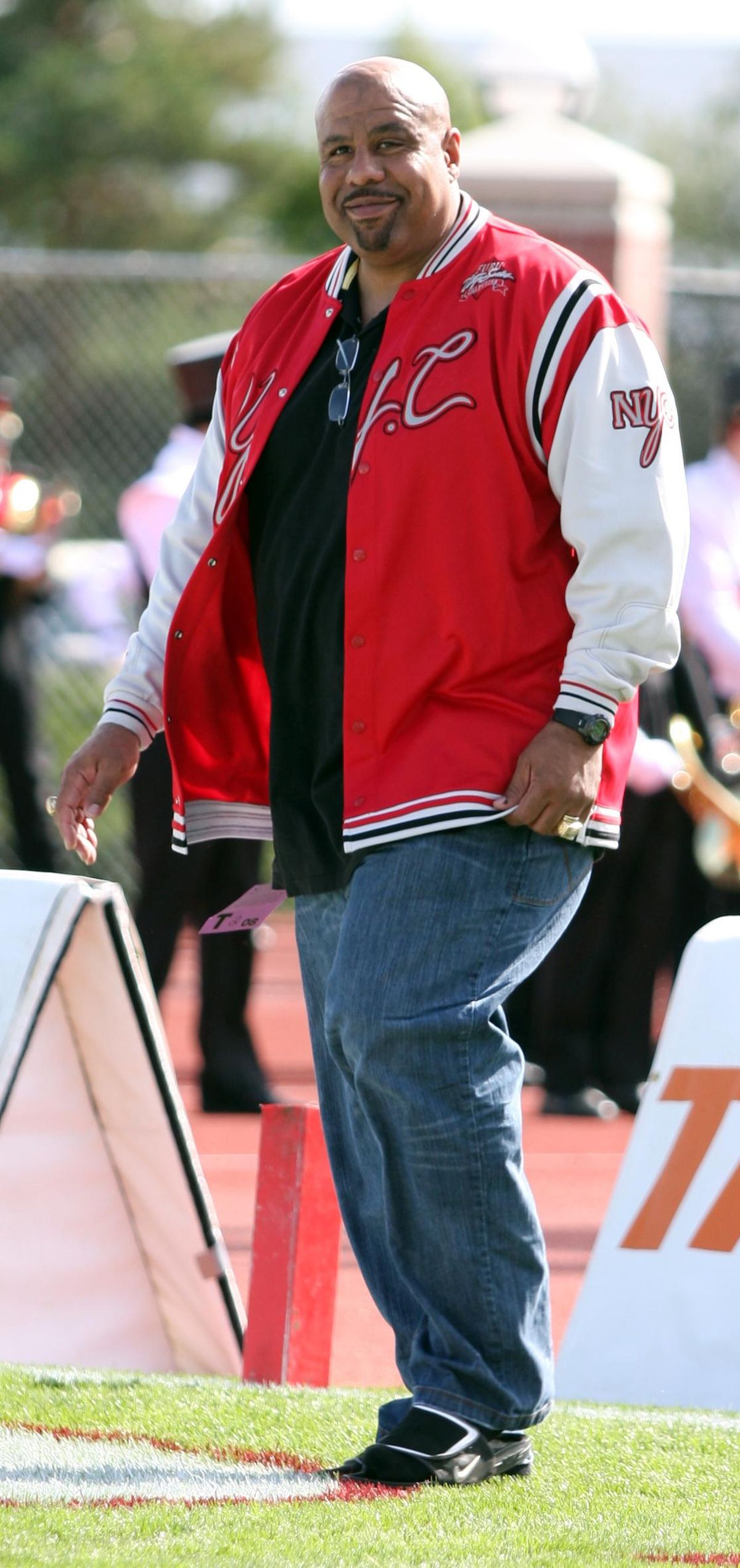

Former Eastern Washington lineman Ed Simmons finds peace after years of pain-filled retirement

The last few steps could be tricky. Sometimes he made it all the way down.

Other times he fell.

Simmons told these stories to doctors in 2002, when he was fighting to get disability money from the NFL, the league in which he played for 11 seasons. After myriad injuries, his body was in bad shape.

But the doctors wouldn’t believe him, he said. Even when he showed up to appointments with a locked-up knee, he said they told him he wasn’t really injured.

“I am not faking and I’m tired of people telling me I’m a liar,” he said he told doctors at the time. “I’m not faking this. I want the money that is due to me, and I’m injured. Stop telling me I’m crying about something when I’m reaching out for help, the help supposedly promised me.”

Two decades after his career ended, Simmons, the former Eastern Washington lineman who won two Super Bowls with the Washington Redskins, said he is in a better place physically and emotionally. Eventually, the disability money did come.

But “Big Ed” Simmons hasn’t enjoyed a glamorous retirement since he left the game in 1998.

“It’s a struggle with the retired players, and it always will be. I’ve gotten to know a bunch of the older guys, the pre-’93 guys, and it’s sad,” he said, referring to players who retired before 1993. “They all keep their heads up, they’re positive about everything, not running around crying about the injustice. They talk about it because it needs to be talked about, it needs to be fixed.

“These guys, almost everybody I know, has a knee replacement or a hip, or a shoulder, something wrong with them.”

Mark Rypien knows Simmons well and understands his situation. Their careers overlapped for six seasons with the Redskins, including two championships. He said Simmons was an intimidating person, especially to opponents.

“You have to be a little intimidating. You have to have that edge,” Rypien said. “Ed basically was very quiet, funny as heck, and just a physical specimen that did his job at a very high level.”

But after Simmons’ playing days were over, in some ways that toughness worked against him.

“I think we all went through it as men, and the thing we struggle with is communication,” Rypien said. “That stigma, especially for athletes and football players more so than others, you don’t think people want to hear about your struggles. Yet that’s the most important part. We all want to hear about the struggles, so that we can talk and relate.”

The Redskins drafted Simmons at a time when Eastern Washington was just starting to produce NFL-caliber linemen. They selected the 6-foot-5, 315-pound tackle in the sixth round of the 1987 draft, and he started three games as a rookie.

But, like Rypien, he did not play in the Redskins’ 42-10 Super Bowl victory that season over the Denver Broncos, having suffered a season-ending right knee injury that November.

Over the next 10 seasons, he made 101 starts and played in 139 games. That included an appearance in Super Bowl XXVI, but only that. His knee was in bad shape, he said, and playing on the Metrodome turf wasn’t good for it. He did not start and played only a little.

A few years later, in 1997 when he was an established veteran on the Redskins offensive line, Simmons was released. He still had a year left on his contract.

“They said, “You’re not the player you were,’ ” Simmons said. “We got graded every week, and our offensive line coach would put the grade on the board. My name was at the top of the list 12 or 13 of our 16 games. So if you’re the best lineman, how do you get released?”

Simmons went to minicamp with the St. Louis Rams and chose to retire before training camp because his knee was in bad shape, he said.

“When I first retired, I still felt like I was an NFL player. That was all I was,” Simmons said. “It was something you don’t prepare for, especially when you don’t see it coming.”

Trent Pollard’s NFL career overlapped the latter part of Simmons’: The former Eastern Washington lineman spent 1994 through 1996 with the Cincinnati Bengals.

But after that time, he tore a ligament in his knee and never played in another game. It was as if he had disappeared from the NFL’s sight, he said.

“Once you’re injured, you don’t have anybody talking to you, breaking things down, the ins and outs of it,” Pollard said. “They send papers to your house, but a lot of it, I didn’t understand.”

Lots of players just slip away like that, Pollard said, and have a difficult time transitioning out of the NFL.

“The untold stories,” he said. “It doesn’t keep that NFL shield shiny.”

Pollard has made the transition, though, largely because of the support of his family. He leaned on his parents – who had attended every home Eastern Washington game during his time there – and his fiancee, who is now his wife.

“I was a big guy, so I needed two places to lean,” Pollard said.

At the time, Pollard’s younger brother was in high school and their dad was the football coach. Dad insisted Pollard come help him coach, so he did.

“That gave me something I had to go do every day, something to look forward to,” Pollard said. “And the next thing I knew I was stuck there.”

Pollard stayed in education and is a student-family advocate in the Seattle School District.

Simmons was leaving the NFL at the same time but wasn’t physically well enough to work.

He invested his money but lost almost all of it, he said, and coached and worked a few jobs near his home in the Tri-Cities. But over the next decade, his physical health was so poor he could not be on his feet for long periods of time, so he packed up and moved back to Washington, D.C., to be closer to the NFLPA and the support network he had there, in 2010.

“That way, I was face to face with those guys so they could walk me through the process,” Simmons said.

Simmons played in two eras of the NFL, sandwiched around 1993. That year is significant because it marked a change in the league’s pension compensation.

The 1993 collective bargaining agreement between the NFL and its players association significantly boosted the value of retirement plans and pensions. It also established full free agency, leading to an exponential growth in salaries.

But that increased compensation affected current players, not retirees. It wasn’t until the 2011 CBA that those pre-’93 players saw their pensions increased, as part of the Legacy Fund.

As it is now, vested retirees – players who are on a team’s roster at least three weeks of three seasons – receive approximately $363 per month for each season they played before 1993. That number had been $250 until the 2011 CBA increased it.

Veterans who played from 1993 to 1996, like Simmons, receive a similar amount – $363 – per month for every season they played.

The 2011 CBA also allowed retirees to apply for disability benefits on a points basis: The more physical ailments the doctor identifies, the more points accrued. Simmons’ application for Total and Permanent Disability was accepted in 2012, he said, but that disability expires now just as his pension comes on board.

Rypien commends the league for those changes but said it could do more. He said the NFL Players Association has “an obligation to the players who are playing today but also to the players who paved the way for the players who are playing today.”

Fairness for Athletes in Retirement is one organization pushing the NFLPA to negotiate for more equity in those pensions in the next CBA (the current one expires in 2021). According to FAIR’s website, pensions for current NFL players are expected to be three times the value of what players received in 1992.

Many players from his era are similar, Simmons said: They didn’t earn as much as current players do, and they don’t have that second career to bridge the gap between their playing days and when their pension kicks in – which for Simmons was just this year. He turned 55 at the end of December.

Mike Kramer didn’t coach at Eastern Washington until after Simmons was in the NFL, but he planned against Simmons as a defensive coach at Montana State.

“What a phenomenal career he had,” Kramer said.

Kramer said he understands what Simmons has been through since retiring because he has seen so many others go through it.

“I think a lot of NFL guys, all of a sudden they drift, and what are they supposed to do?” Kramer said. “What Ed went through is not uncommon. It’s a form of PTSD.”

When Simmons left the Redskins, he was stepping away from a game that had been his primary focus, and from people – like the heralded “Hogs” on the offensive line – who had been his support for a long time.

“That group especially, the offensive line, that was a fraternity of its own,” Rypien said. “He took a lot of pride in being a Hog.”

But two decades later, Simmons leans even more on his family for that support and has found a new focus: his grandkids.

Living in the D.C. area, Simmons and his wife, Dilia, came back to the Tri-Cities in 2015 to see Dilia’s mother, who was in hospice care. While there, she died, but at the same time Dilia’s daughter was pregnant, so they stayed a month to meet the baby and another month after the birth.

“I spent the greater part of that month with that newborn,” said Simmons, who also has biological grandchildren from a previous marriage. “We didn’t even get halfway across the country and I told my wife that I wanted to move back. I wanted to be closer to family. I loved living in Virginia, but my heart was set on moving back. All I was doing was basically existing.”

So, later that year, they moved.

He now has 10 grandchildren and soon an 11th, and all of them live in or near enough to the Tri-Cities.

This year he attended four Eastern Washington football games, including the national championship game in Frisco, Texas, where he met up with many former EWU teammates.

Eric Stein kicked and punted at Eastern from 1984 to 1987, when Simmons was there. He also attended the game in Frisco and had seen Simmons only sparingly since their college days.

“There hasn’t been a lot that has changed,” Stein said. “Back then, he was a gentle giant, a very humble, really good person. Put him on the football field and look out. … But off the field, he was really nice to anybody and everybody.”

Simmons had planned also to attend the Eagles’ playoff game against UC Davis a month earlier, but that changed when he had the opportunity to take care of his grandkids.

“You see where my heart and my mind is,” Simmons said.

Rypien and Kramer said much the same.

“Some of the voids they fill in your life, it definitely helps. You need something to keep going,” said Rypien, who has two young grandkids. “For Ed, I’m sure that’s been a blessing.”

After coaching the better part of the last four decades, Kramer spends much of his time in Central Washington, farming with his son-in-law.

“The one thing that is a magnet for all of this is grandchildren,” Kramer said.

So, it doesn’t surprise Kramer that Simmons is willing to sacrifice his body again – this time for his grandkids.

“Overall yes, I’m in a good place. Financially, enough comes in to pay the mortgage, the car note, keep the heat on and the house full of food and I’m prepared for the kids whenever they come,” Simmons said. “We have a good time here. We play, we watch movies. They wear out the little bit of strength with my back, and I let them. When they leave, I’m exhausted.”

He likes the summertime even better, because they have a pool, and the grandkids love to play in it with him.

There, he said, he can stand up and feel no pain.