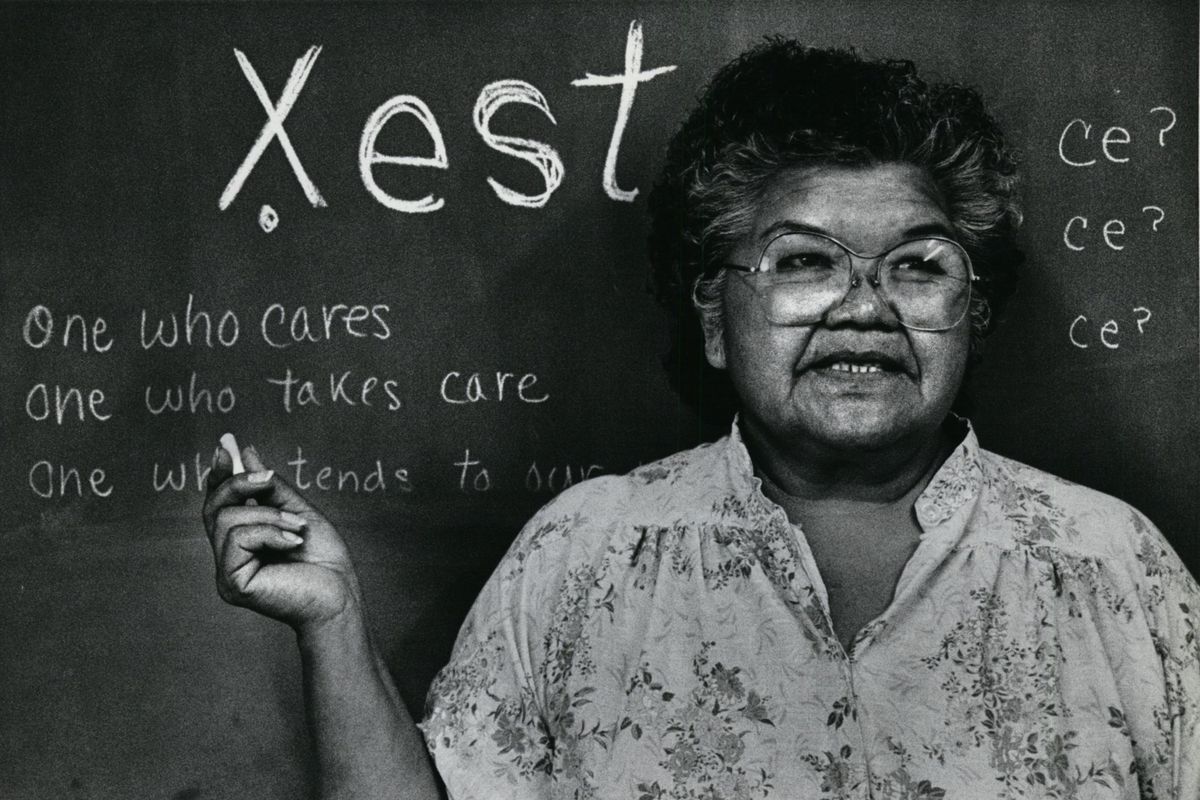

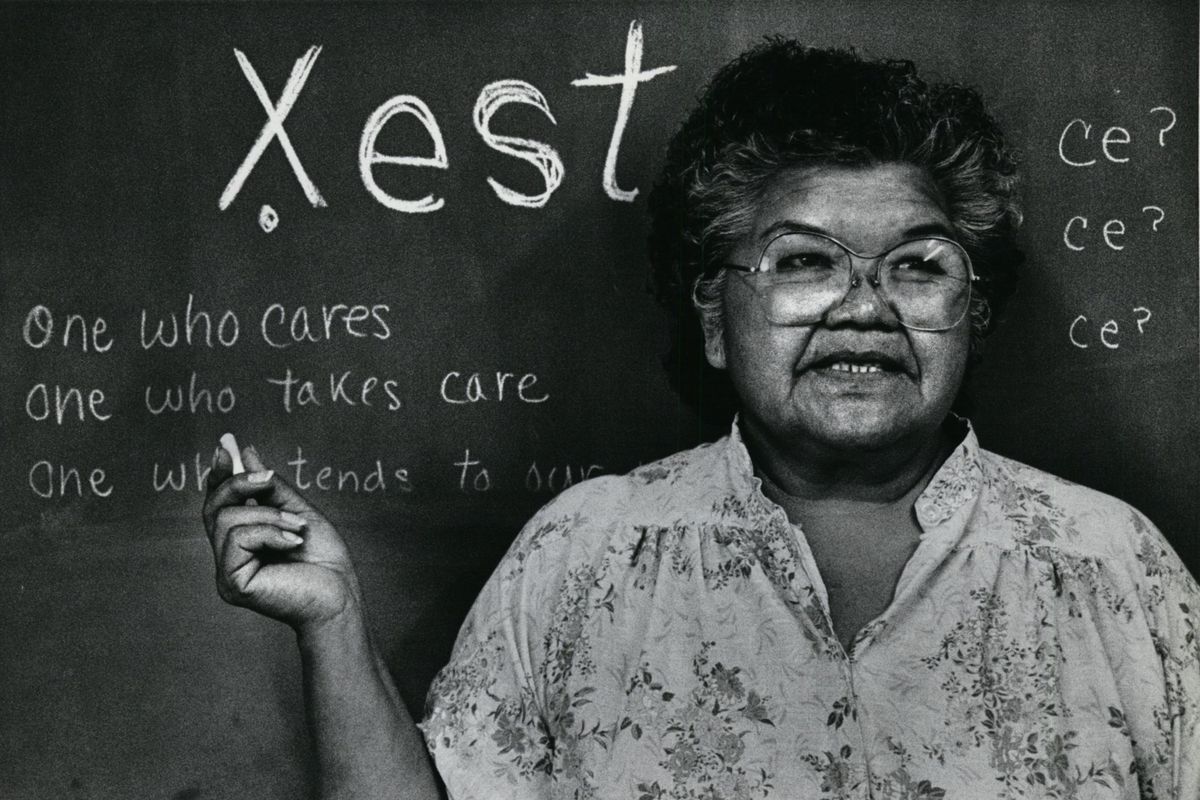

Pauline Flett, who revived Spokane Tribe’s Native language, dies at 93

Members of the Spokane Tribe of Indians are mourning Pauline Flett, an elder who played an instrumental role in preserving the tribe’s Salish dialect and teaching the language to younger generations.

Flett died of natural causes in a hospital on April 13, relatives said. She was 93.

Her death leaves only one or two tribal elders who are completely fluent in the Spokane Salish dialect, which Flett worked tirelessly to document over the course of five decades.

Even in her last days, as her eyesight waned, she was known to spend hours reading and filling notebooks with meticulous notes and translations.

“She was determined not to let it die – determined to get as many people involved with the language as possible,” said Laura Brisbois, one of Flett’s daughters.

Flett grew up in a Salish-speaking household in the West End area of the Spokane Indian Reservation and didn’t learn English until she began attending school.

She was born in 1926, at a time when the tribe’s way of life was being irrevocably altered. The Long Lake Dam already had blocked most of the Spokane River in 1915, and the Grand Coulee Dam went up on the Columbia River in 1939, putting an end to annual salmon runs that had provided both food and great cultural significance.

Guided by a professional linguist in the 1970s, Flett was among the first to use a written alphabet to transcribe words and legends that had survived for centuries only through oral storytelling.

She co-wrote the first Spokane-English dictionary and multiple updated editions, and taught the language at Eastern Washington University, which granted her an honorary master’s degree in 1992. Her notes are held in collections at EWU and the Smithsonian Institution, among other places.

She also was a pillar of the tribe’s language education programs, which include an immersion school for children that opened four years ago in Wellpinit. She was an expert on the nuanced meanings of Spokane words and grounded her teachings in traditional stories and songs.

Barry Moses, a tribe member who knew Flett from the time he was a child, called her “the driving force of bringing the language into the 21st century.”

“Virtually everything that exists in the Spokane language today, that’s ever been documented, has been a result of her work,” said Moses, who runs a nonprofit called the Spokane Language House. “Now we’re in the process of analyzing this extensive archive that she created: thousands and thousands of pages of oral histories and stories and interviews and documents that she kept over the period of 50 years.”

That work, Moses said, has formed the foundation of the tribe’s Salish curriculum, enabling adult speakers to pass it along to children even after multiple generations did not learn it as a first language.

“If the Spokane language has any future at all,” he said, “it’s indebted to Pauline Flett.”

Salish is a family of languages spoken by indigenous people across the Pacific Northwest, with variations in vocabulary and sentence structure. Spokane and Kalispel are closely related dialects, while Coeur d’Alene and Colville-Okanogan are more distinct. Coastal Salish languages are mostly incomprehensible to local tribes.

Salish, like indigenous languages across North America, has been at risk of disappearing after a century of oppression beginning with the first settlers, including boarding schools that punished Native Americans for speaking anything but English.

According to those who knew her, Flett’s mission to preserve Spokane Salish began after she met Barry Carlson, a linguist and anthropologist who started working with the tribe as a graduate student in 1969.

In a phone call from his home in Victoria, British Columbia, Carlson recalled how he set to work interviewing tribal elders.

“Pauline was around, of course, but I wasn’t really working with her. I was working with the older people that still knew all the stories and everything,” Carlson said. “That’s normally what you do with a language that’s endangered. You want to work with the best speakers.”

After about 10 years, Carlson said, the tribal office asked him to teach courses using the 47-character alphabet he had developed to represent all the unique sounds of Spokane Salish.

“As it turned out, everybody showed up for these lessons. You know, it’s a small place, and I knew everybody by then,” Carlson recalled. “And Pauline was one of the people that showed up for those classes, and she was the real star of the classes. She really picked it up fast.”

Carlson noted that Flett and her elders had never had a way to capture all the richness of Spokane Salish on paper, including the names of places, plants and animals, and detailed legends about their tribe and the world around them.

“And what happened with Pauline was, once she could write it down, she just kind of went crazy, and she just started writing everything down,” Carlson said. “I think she just really loved doing it. She was just a natural linguist.”

They continued working together through the 1980s and early ’90s, with Carlson visiting often from the University of Victoria. He said Flett was an expert at breaking down Spokane words into their component parts. She and other elders were often consulted to create new words, keeping the language up to date with the modern world.

For example, Moses said she coined a word for “computer,” combining the root word sc̓mqin, meaning “brain,” with the suffix -éyeʔ, meaning “pretending.” That becomes sc̓mqnéyeʔ, meaning “something pretending to be a brain.”

“She was just so dynamic. She had such deep knowledge of the language,” said Marsha Wynecoop, the Spokane Tribe’s language education director, who began working with Flett in the 1990s. “You could basically ask her anything and she could explain it to you, or almost transcribe anything that you put in front of her.”

Carlson said he hopes the tribe’s language programs will continue to be self-sufficient in Flett’s absence.

“They’re going to have a hard time getting along without her,” Carlson said. “They have a lot of material, but they won’t have anybody with her expertise to analyze things and come up with new material because there just aren’t native speakers left.”

Flett raised 11 children and left behind a family that includes about 90 grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. Another of her daughters, Nin Day, said Flett loved playing guitar and piano at church and family gatherings.

Viola Frizzell, 95, who grew up with Flett, said Flett was always in good spirits, even after she broke her hip and came down with pneumonia.

“She was never without that smile – never, never,” Frizzell said.

Normally this time of year, Frizzell and Flett would be preparing to take elementary students on field trips to gather traditional foods, like the camas root. And Flett, of course, would teach them words and phrases in Spokane Salish.

“With the language, you have everything,” said Carol Evans, chairwoman of the Spokane Tribal Business Council. “She dedicated her life to that, and we’ll be forever thankful.”