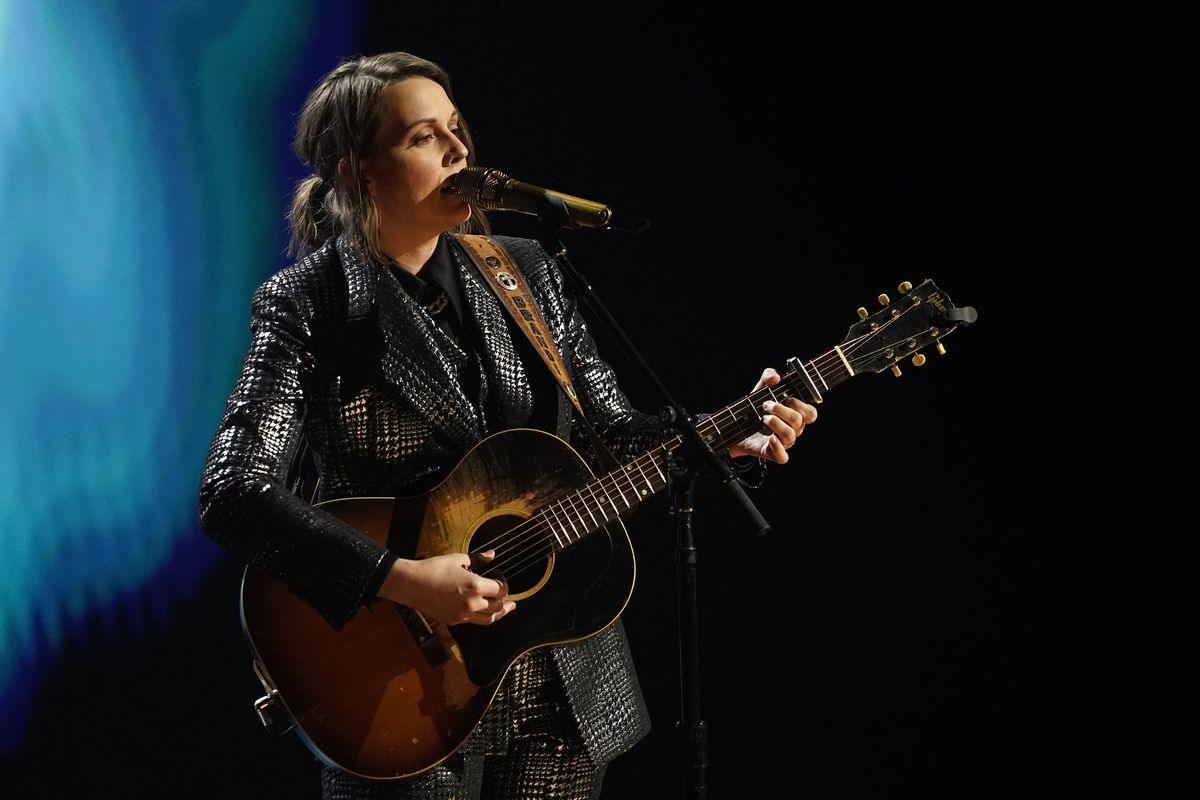

Brandi Carlile opens up about overcoming insecurities, her latest Grammy win and her new memoir

SEATTLE – In some ways, the past three years have felt like 30, and, during that stretch, it seems Brandi Carlile’s had half a lifetime’s worth of productivity.

On the strength of 2018’s superb “By the Way, I Forgive You,” Carlile and the guitar-wielding Hanseroth twins who flank her became the talk of the Grammys, earning a wave of new fans and taking the trio to even bigger stages like the Gorge Amphitheatre and Madison Square Garden.

They produced and co-wrote a career-rejuvenating Tanya Tucker album, not to mention another Secret Sisters record, both of which also caught the Recording Academy’s eye. They made headlines with a tribute concert to Joni Mitchell’s iconic “Blue” album, and Carlile formed an all-star country band aimed at shaking up the dude-dominated country music world.

She also wrote a book. Released April 6, the Maple Valley, Washington, singer-songwriter’s memoir, “Broken Horses,” follows Carlile’s journey from a “zero-stoplight town called Ravensdale” to White House invites, offering an unvarnished look at the highlights and hardships along the way.

The acclaimed singer-songwriter, who hauls her own hay and once had her drink swiped by Chaka Khan while jamming with Elton John at Mitchell’s place (you’ll have to read the book for that one), ties the music she’s made and the songs that made her into her life story.

It’s told with the candor of a campfire conversation, a family photo album by her side and with the wit, humility and earnestness Carlile exudes onstage and in interviews.

We recently caught up with the artist, activist and, now, author to discuss her latest Grammy win, her forthcoming album and, of course, “Broken Horses.” This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Congrats on the Grammy (for best country song). What did it mean for you to have the Highwomen, this project that made a big statement, recognized on that level?

Oh, man, it was cool. It was like when you sing something into a cave, and the echo comes back, it was like, “Oh, they heard us.” They knew what we were saying. “Crowded Table,” it felt really nice for the Highwomen to get recognized for that song, which is really just about love and reconciliation and the importance of waking up every day and doing the work but coming back at the end and coming back to love every time.

When I heard about “Broken Horses,” my first reaction was, “When the hell did she have time to write a book?!” So, when the hell did you have time to write a book?

Well, it was something I always thought would take a really, really long time, but the stories just kinda exploded out of me. The editing process was quite time-consuming, but I had this whole pandemic year to do that.

Why did it feel like the right time to do the book?

I think that like a song it just comes to you when it comes to you. I had read a couple of books, and I started thinking about how I wished I had a certain kind of book growing up. And I was writing fewer and fewer songs and more stories and little dissertations and little literary pieces that I felt like I was being called and led toward a writing project.

When you announced the book, you posted a video talking about how you were overcoming insecurities around not finishing high school and feeling like a ninth-grader hiding in the bathroom again. What was it like to grapple with those things while also experiencing all these highs in your career?

I grapple with these things when I’m experiencing the highs specifically because the highs make me feel like I’m hiding something about myself. They make me feel like people don’t know or that they think I’m something I’m not.

I feel like, to a certain extent, I’ll always be coming out of the closet as something other than whatever a public person is presented as. It’s always an issue in our industry in the way that we platform people. We gloss over the things about them that make them feel inadequate or insecure, and they change into beautiful clothes that they give back at the end of the day.

So when I’m experiencing highs, if things are happening for me at the Grammys, or I’m selling tickets or an album does really well, I think, “Yeah, but people don’t know the whole story.” And I want ’em to know the whole story. Because if they know and they still accept me, then I belong here. Otherwise, I don’t feel like I do.

Were there any parts of this book that were particularly difficult for you to put out there in such detail?

Yeah, I think there’s a part on every page like that. And then there’s a part, every time I turn a page, that I had to take a pause after I had written it and said, “Do I really want …” and then I made the decision every time to just keep going and keep turning the page and leaving it.

As you were re-examining aspects of your life, was there anything you discovered about yourself?

Yeah. I mean, I discovered how vivid my memory is and that there’s real cohesion around that. I discovered that I have a voice when I write, like I have an identifiable way of communicating that, maybe it’s because I didn’t finish school, maybe it’s because of writers that I’ve been drawn to for (different) reasons, it’s conversational.

And I think I discovered that at the root of all of it is my need to be with people and be understood by and to understand people. It draws people closer to me, and it draws me closer to other people, and that’s kind of at the heart and soul of the whole endeavor.

It sounded like you (initially) intended it to be more explicitly the behind-the-scenes of some of the music and songs. It still does that, but when did you realize this was going to be a much more personal book?

First page. I knew in my mind that I wanted it to be this events-based book – that I was writing about either what led me to write a song or how a song influenced an event. But when I put pen to paper, like all of my writing, what I intended to do just didn’t get done. Something else got done. It was a lot more authentic.

After you finished or even as you were going through, was there anyone you were thinking to yourself, “Oh, man, I wonder what so-and-so is gonna think when this is finally out there?”

Oh, God, man, absolutely. Just the whole time. I’m not gonna lie, that is the really daunting and unsettling part of doing this. I’ve had so many phone conversations, and so many cathartic and uncomfortable things have been said as I have stumbled clumsily through this process.

It has not been easy, but it’s felt right, and it’s actually healed relationships. That kind of catharsis, that’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing, and right now it’s kind of a once-a-week thing.

You share an anecdote in the book, (from) the (Seattle) protests that erupted after (former President Donald) Trump’s travel ban on Muslim-majority countries. Where exactly was the protest?

It was downtown near Westlake and I got invited by the Inslees to sing “The Times They Are a-Changin’” by Bob Dylan. But when I got there, the protest had taken on a very different shape and it was entirely inappropriate for me to sing anything or for me to even speak into a microphone at all. The PA system was malfunctioning and we had brought a sound person with us and we found ourselves instead repairing cables and trying to fix the actual amplification of the actual people of color and the actual people that were affected by the ban. It was a metaphor for not centering oneself when you are unaffected. That is, it’s key, because amplifying those who are, is what we should all be striving to learn to do.

Was there anything from that experience you’ve taken with you as we’ve watched America having this identity crisis and reckoning around systemic racism?

Yeah. That’s how God teaches me things, he drops pianos on my head out of second-story windows. I mean, I had to learn about not centering myself on an actual stage. I wound up on my knees untangling cables [instead of performing] and that’s a metaphor for where we all should be right now. I have taken that into my activism and into my allyship every day – every day that I’ve walked in it I have thought of that moment.

You talk about two sides of your personality – the entertainer who enjoys the spotlight, but also back home making trails around your property with a machete and ripping around on four-wheelers. Especially the last few years (amid) these crazy experiences, what is it like to be able to come back from that and have that quieter life in Maple Valley in the house you bought when you were 21?

Well, it used to feel really whiplash-y, you know. But as I’ve gotten older and started approaching my mid-30s to now, I’ve found ways – mostly my wife’s help – I found ways to integrate both of those people, both of those personalities in me and make them one. So, I kind of am the scalawag at Joni’s and the girl that plays Madison Square Garden in the trails, too.

You made the comment, “I don’t know who I am as an artist after this album and after Joni.” Can you explain what you mean by that and what your mentality is like heading into the next record?

Joni shook me, actually. She shook me because she’s unlocked and there’s very few people that are unlocked. She’s in touch with the source of where music comes from, the muse, you know, and I’m not unlocked.

But Joni shook me because I realized that more and more as an artist, I was wanting to become the kind of songwriter that would write a song that would impress Joni Mitchell one day. It seems trite, to have that as a goal. But it’s so [expletive] impossible that it’s a little bit like climbing a musical Mount Everest. I didn’t need another “Joke,” I didn’t need to write a country album anymore, I didn’t need to write for Tanya Tucker. I wanted to write for me, but I wanted to write in a way that was at least nodding to the unlocked.

Coming off that period, how do you feel that affected the songs once you finished the album?

It really affected it, man. The book specifically affected them. It affected the twins, too. I think the three of us were writing this record based on having read the book. Then we wrote the record because of what the book reminded us of, and that sets it apart. That makes it a different kind of album.