Making Spokane legislative districts more competitive will be difficult for redistricting commission

When a special commission redraws the boundaries for Washington’s legislative districts this year, some residents will urge its members to make more of those 49 districts competitive for candidates of both parties.

The Washington Redistricting Commission, a special body appointed every 10 years with four voting members named by legislative leaders, began its work last month and recently selected a fifth nonvoting chairwoman to run its meetings.

At least three of the four voting members must settle on new boundary lines for congressional and legislative districts that will have equal population based on the 2020 Census, by the end of the year.

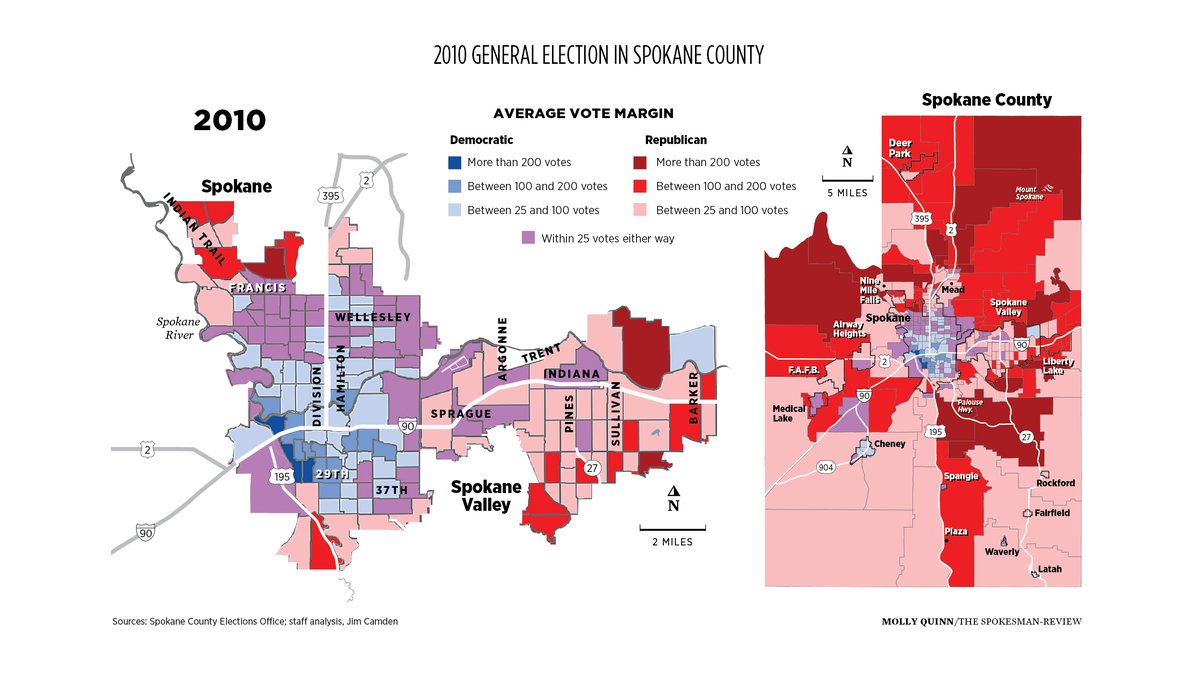

Creating new competitive or “swing” districts in the Spokane area will be difficult, a computer analysis of the five legislative districts in the county and current voting patterns shows.

Since the current boundaries were drawn 10 years ago, those five districts totally or partially in Spokane County have become more polarized, with strongly Democratic precincts concentrated in the City of Spokane and strongly Republican precincts in the city of Spokane Valley, the suburbs and rural areas.

The 2011 redistricting, which required most Eastern Washington districts to expand to account for greater population growth in the I-5 corridor, wiped out Spokane’s only “swing” district where Republican and Democratic legislative candidates had been elected recently to the Legislature.

At that time, the 6th District was primarily an urban and suburban district split between the city of Spokane and its nearby suburbs on the south, north and West Plains.

Although historically a GOP stronghold based on Spokane’s South Hill, the 6th had been redrawn to wrap around the city’s north and west neighborhoods 20 years earlier when the county lost an entire legislative district in northwest Spokane. While some precincts in the northwest corners of the city had strong Republican voting areas, others along the North Maple and North Monroe corridors were tossups and the lower South Hill was becoming more likely to back Democrats.

By the middle of the first decade of this century, the district elected its first Democrats to the state Senate and House since the 1930s by relatively narrow margins. In 2010, Republicans took back those seats.

When the lines were redrawn, some of those west Spokane “tossup” districts were added to the reliably Democratic 3rd District. The boundaries of the 6th were extended west to the county line, adding Airway Heights, Fairchild Air Force Base, Cheney and Medical Lake, and to the southeast below the city of Spokane Valley, which tended to vote Republican.

For the remainder of the decade, the 6th District has sent Republicans to the Legislature and the 3rd District, which hasn’t elected a Republican legislator since 1992, has been solidly Democratic.

The 4th District, which has its population centered in Spokane Valley, is also solidly Republican, as is the 7th District, which includes parts of north Spokane County along with four other northeast counties, and the 9th District, which has part of south Spokane County along with five southeast counties.

In drawing district boundaries, it would be difficult to add precincts from the city of Spokane to make any of those three districts more competitive for Democrats because of court rulings that say redistricting should avoid splitting “communities of interest” like cities whenever possible.

Based on the most recent population estimates for Washington, a legislative district will have about 156,250 people. Estimates put the population of the city of Spokane at about 227,600 people, which means at least some of its precincts must be part of districts outside the city limits.

The 3rd District is the only one that is completely within the city, with most of the remaining Spokane precincts part of the 6th District.

As the map of last year’s voting patterns in the county’s legislative districts suggests, the city might be divided along recognizable lines, either east and west along the Division Street corridor or north and south along the Spokane River or Interstate 90.

That would create two districts with a greater mix of Democratic, Republican and “tossup” districts. But it could also violate the community-of-interest standard because there would be no city-only district as suburban or rural precincts to the north, south or west of the city limits would have to be added to reach the population requirements. Adding precincts to the east of the Spokane city limits would mean splitting precincts away from the city of Spokane Valley, another community of interest.

A comparison of the voting patterns from 2020 and 2010, the statewide election before the last redistricting, also shows a shift in the concentration of Democratic support inside the city of Spokane, and Republican support in precincts outside that city.

Because a single race can be heavily influenced by the candidates’ personalities or a key issue on which they differ, computer analysis took the average of a series of results in each year that included countywide totals for federal, state and county offices.

That analysis shows that in 2010 there were far more precincts in the city of Spokane that were up for grabs, with the average margin of all the races no more than 25 votes for either party, and relatively few that were so solidly Democratic or Republican that the average margins for candidates were greater than 200 votes.

Ten years later, many of those “tossup” precincts in the city of Spokane have been replaced by precincts that are at least nominally Democratic, and a block of precincts from West Central through downtown and up the South Hill to the Comstock area are so heavily Democratic that the average margin is more than 200 votes in favor of that party.

At the same time, more precincts in south and north Spokane County, as well as the West Plains, Mead and areas north of the city of Spokane Valley, have average margins that are greater than 200 votes in favor of Republican candidates.

Some precincts in those areas that were rated as tossups in 2010 shifted to Republican by last year’s election, and many that were mildly Republican 10 years earlier are now a deeper shade of red.