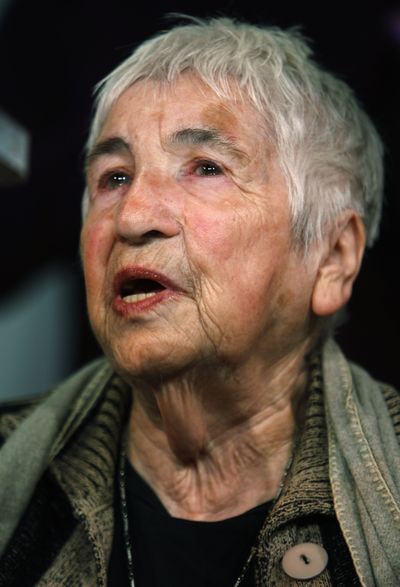

Auschwitz survivor who fought racism with music dies at 96

BERLIN — Esther Bejarano, a survivor of the Auschwitz death camp who used the power of music to fight antisemitism and racism in post-war Germany, has died at 96.

Bejarano died peacefully in the early Saturday at the Jewish Hospital in Hamburg, the German news agency dpa quoted Helga Obens, a board member of the Auschwitz Committee in Germany, as saying. A cause of death was not given.

German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas paid tribute to Bejarano, calling her “an important voice in the fight against racism and antisemitism.”

Born in 1924 as the daughter of Jewish cantor Rudolf Loewy in French-occupied Saarlouis, the family later moved to Saarbruecken, where Bejarano enjoyed a musical and sheltered upbringing until the Nazis came to power and the city was returned to Germany in 1935.

Her parents and sister Ruth eventually were deported and killed, while Bejarano had to perform forced labor before being sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943. There, she volunteered to become a member of the girls’ orchestra, playing the accordion every time trains full of Jews from across Europe arrived.

Bejarano would say later that music helped keep her alive in the notorious German Nazi death camp in occupied Poland and during the years after the Holocaust.

“We played with tears in our eyes,” she recalled in a 2010 interview with the Associated Press. “The new arrivals came in waving and applauding us, but we knew they would be taken directly to the gas chambers.”

Because her grandmother had been a Christian, Bejarano was later transferred to the Ravensbrueck concentration camp and survived a death march at the end of the war.

In a memoir, Bejarano recalled her rescue by U.S. troops who gave her an accordion, which she played the day American soldiers and concentration camp survivors danced around a burning portrait of Adolf Hitler to celebrate the Allied victory over the Nazis.

Bejarano emigrated to Israel after the war and married Nissim Bejarano. The couple had two children, Edna and Joram, before returning to Germany in 1960. After once again encountering open antisemitism, Bejarano decided to become politically active, co-founding the Auschwitz Committee in 1986 to give survivors a platform for their stories.

She teamed up with her children to play Yiddish melodies and Jewish resistance songs in a Hamburg-based band they named Coincidence, and also with hip-hop group Microphone Mafia to spread an anti-racism message to German youth.

“We all love music and share a common goal: We’re fighting against racism and discrimination,” she told the AP of her collaborations across cultures and generations.

Bejarano received numerous awards, including Germany’s Order of Merit, for her activism against what she called the “old and new Nazis,” quoting fellow Holocaust survivor Primo Levi’s warning that “it happened, therefore it can happen again.”

While addressing young people in Germany and beyond, Bejarano would say, “You are not guilty of what happened back then. But you become guilty if you refuse to listen to what happened.”

She also didn’t shy away from criticizing present-day German officials, such as when tax authorities canceled the charitable status of the country’s biggest anti-fascist organization. The decision was later reversed.

In a letter of condolence to her children, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier wrote that Bejarano had “experienced first-hand what it means to be discriminated against, persecuted and tortured,” and lauded her educational work.

“We have suffered a great loss in her death,” he added. “She will always have a place in our hearts.”