Spokane medical lab science program, one of only three accredited in Washington, does crucial but often unseen work

Arguably the best-kept secret of the hospital takes up an entire floor of the basement of Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center.

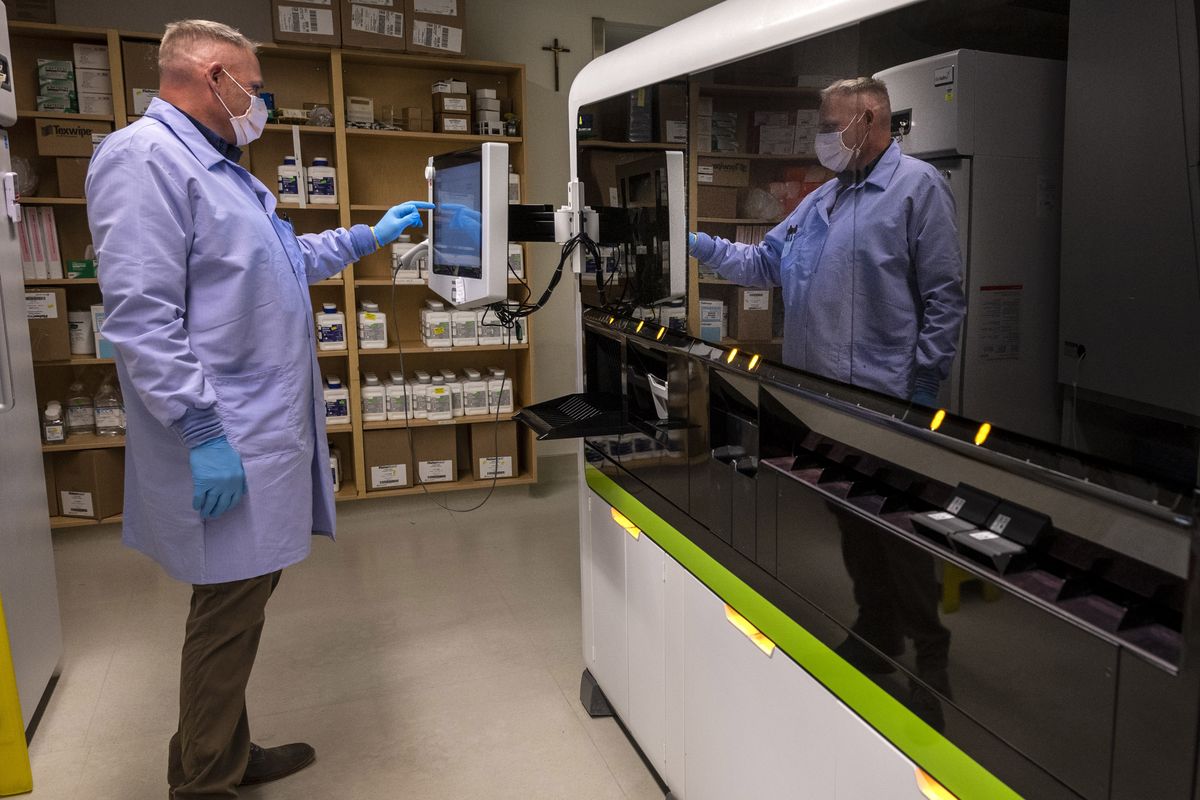

The diagnostic laboratory, where analysis takes place on almost every test or sample from patients in the hospital, as well as some from other Providence clinics in the region, in some ways resembles how Hollywood depicts laboratories.

Scientists wearing purple lab coats prepare samples, run tests and report results. Refrigerators, which at first glance look like coolers, hold trays with vials of liquid samples, blood or otherwise. One massive instrument with a conveyor belt snakes through the chemistry lab carrying urine or blood samples, which can be tested in nearly 60 ways. Computer monitors accompany the upgraded version of microscopes, which have detailed lenses that enable scientists to see blood cells clear as day on their screens.

Two relatively new instruments were brought in last winter to run COVID-19 samples in large batches for Providence facilities throughout Washington and Montana. Large tubes carry samples down from different floors of the hospital to the lab, much like at a mailroom or bank. There’s a special tube line just for priority samples from the emergency department.

The microbiology lab has microscopes, stacks of plates smeared with samples, where bacteria growth can be evaluated and viruses or infections diagnosed.

While technology has come quite far, the path to diagnosis begins in this laboratory with the expertise of the team of scientists and support staff there.

It is also here that future medical laboratory scientists can train through Providence’s year-long education program.

There are only three accredited medical laboratory science programs in Washington state, at the University of Washington, Heritage University in Toppenish and Providence’s program in Spokane. There are seven medical laboratory science programs in the greater Pacific Northwest, including the three programs in Washington.

Zac Ziegler and Marisa Klein-Chavez just graduated from the program this month, after a year of long days in the lab.

Never mind the pandemic, the two recent graduates started their path to becoming medical lab scientists last July. Soon, they will both sit for their board exams, which they need to be certified as official scientists.

They are in a great job market, with the demand for lab scientists in the medical field at a high.

“We’re in a critical shortage right now,” said Laurianne Mullinax, who directs the Providence School of Medical Laboratory Science. “We cannot fill positions – that’s not just Providence, not just Spokane, that’s nationally.”

Even before the pandemic, in 2018, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the demand for lab workers was up 13%.

Now, with many scientists positioned for retirement along with those who burned out after the onslaught of COVID-19 testing, Mullinax said, the shortage is likely worse.

“I have people emailing me from all over the country saying, ‘Send us your grads; we’ll give them this huge relocation package and sign them,’ because there are areas that are desperate,” Mullinax said.

There are several classifications of laboratory workers that support the work of a medical diagnostic lab, which are found in each hospital and some clinics, as well as independent labs.

To become a medical laboratory scientist through an accredited program, competition is fierce and programs are scarce in the Pacific Northwest.

Students should have a bachelor’s degree or be working towards completing one in a science, usually biology or chemistry. Then the application process begins.

At Providence, the program can only hold up to 16 students in each cohort, with two each year. One cohort begins in the summer, while the other begins in the middle of winter. Students pay tuition for the program, but scholarships, loans and potential tuition reimbursement are available.

Job openings are aplenty too. Both Ziegler and Klein-Chavez are already working in parts of the lab at Sacred Heart Medical Center as they prepare for their board exam.

The job market and stable pay excites them both. The average starting wage is about $29 an hour, Mullinax estimates.

Ziegler said the Providence program helped prepare his cohort for future jobs.

“This program did a really good job of challenging us, throwing us in the deep end sometimes, and not necessarily setting us up for failure, but making us think critically and work together to solve problems,” Ziegler said.

Part of the Providence program requires students to do clinical rotations not just at the Sacred Heart lab, but at labs throughout the Inland Northwest. Klein-Chavez did clinicals at Deaconess and LabCorps. Ziegler got to experience lab work in a rural setting at Mount Carmel Hospital in Colville.

For every patient diagnosed with viruses or infections, from a urinary tract infection to COVID-19, there is a team of scientists verifying and confirming those test results. Although often not seen or heard from, laboratory techs and scientists are often in communication with nurses and doctors about tests.

The microbiology lab will often provide a potential list of medications that could fight the infection or virus they confirm in their lab. Communication amongst providers, up and down floors on the hospital, is a vital part of the job too. Mullinax said the program incorporates a lot of teamwork and requires communication skills.

Klein-Chavez remembers mock calls where she would practice reporting critical results. Ziegler, who worked as a lab assistant in the microbiology lab for a year before entering the program, said he talks with nurses ordering tests to ensure the right tests are being conducted.

“The more you can interact and do better interpersonal communications, the better it is for patient care,” Mullinax said.

For both recent graduates, being a piece of the patient’s care in an indirect way is part of why they are excited about the careers they chose.

In a world of automation, scientists who have learned the underlying principles and can identify viruses or when things look wrong are still crucial to a patient’s diagnosis.

“Those numbers mean something,” said Klein-Chavez, who works in the hematology part of the lab. “There’s always going to need to be someone there to give it their seal of approval and send it on its way.”