How it could end: With vaccines and variants, is 2021 going to be any different?

Travis Albo, a pharmacist with Omnicare, gives Wallace McGregor his second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine on Feb. 1 during a mass vaccination at the Fairwinds Retirement Community in Spokane. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

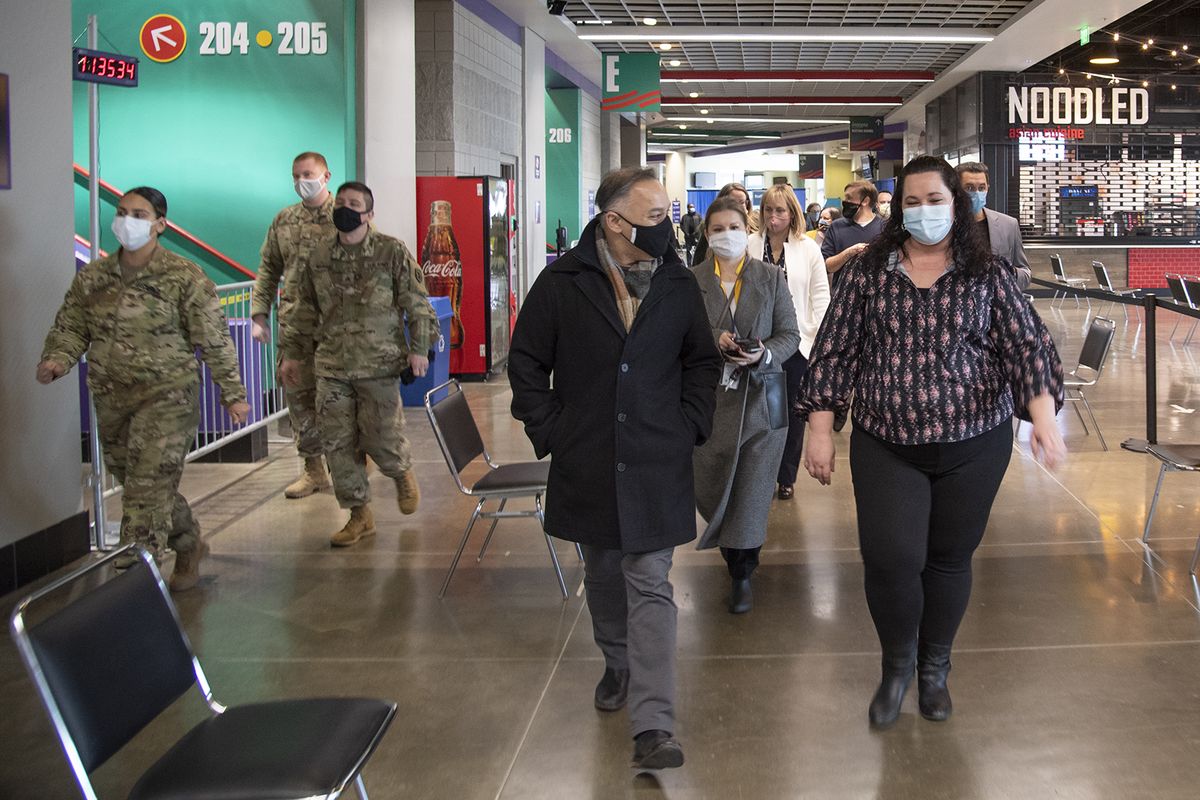

When Dr. Umair Shah moved to Washington in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, his primary task was monumental: distributing vaccine doses to the state’s residents quickly, efficiently and equitably.

Three months into his new gig as State Secretary of Health, Shah is quick to acknowledge the hard work ahead in the next few months as residents anxiously wait their turn to get vaccinated.

He visited the Spokane Arena mass vaccination site in February, watching over the work of state and local health workers, with an assist from the National Guard, as they set up a facility that could only be imagined in a pandemic. Instead of hockey fans lining up for pizza, people sit for 15 minutes after receiving a vaccine.

It’s a surreal point in human history.

During his visit to Spokane, Shah reflected on what he called the “lighthouse” he envisions by fall 2021.

“My end goal is for us to be at a point where at the beginning of the school year, we’re all looking at a situation where we’re feeling comfortable and everyone has done enough: gotten vaccinated, the three W’s (washing hands, watching distance, wearing masks) and all the other things,” he told The Spokesman-Review last month. “And the mutant strain has not taken off hopefully in a way that we cannot handle, so our kids can go back to school in-person without any hesitation whatsoever.”

The department’s goal is to vaccinate 70% of Washington state’s eligible population by mid-summer.

While that goal might seem lofty or inconceivable now, with a little more than 10% of Washington residents fully vaccinated as of March 8, a third vaccine is now available, and the Biden administration has ordered enough vaccine to cover each eligible adult by May.

What happens between now and this summer, however, could make all the difference.

The Race

For the better part of the year, Washington residents have endured government-mandated restrictions. They’ve worn masks, skipped gatherings and followed testing and quarantine guidelines. When things got ugly this winter, as cases surged and hospitals filled to alarming levels, Gov. Jay Inslee instituted more restrictions. Now that the numbers are coming down, the governor has slowly dialed back some of those restrictions.

None too soon. Pandemic fatigue is real, and after a year of lockdown and illness, we are ready to venture out again. To feel the sun on our faces. To hug our parents and grandparents again.

We’re not quite there yet. But with vaccines becoming more available, a possible end is in sight.

WSU nursing student Dane Lawson loads up a second Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for Mike Partridge, 65, right, during a Spokane Regional Health District vaccine clinic, Tuesday, March 2, 2021, at the House of Charity in downtown Spokane. Hannah Gubitz, WSU Community Health Clinical Instructor is at rear. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

But vaccines alone can’t get us that coveted herd immunity. If we want to get back to work and get back to play, we can’t ditch our masks or gather en masse in the coming months. As mutated versions of the virus continue to circulate, the potential for devastating outbreaks is significant. As has been true most of the pandemic, the future is very much in our own hands.

“How this ends is still very much under individuals’ control, independent of vaccine supply, which is frustrating,” Guy Palmer, pathology and infectious disease professor at Washington State University, said.

If people keep gatherings small or stay home when they feel sick, they drive down the potential spread of the virus and number of new infections, letting that virus strain die.

With thousands of people already infected and recovering from COVID-19 in Washington, it’s possible that the mutated virus has fewer potential victims than it did last year. In essence, the novelty of the “novel” coronavirus, is beginning to wear off.

“Less COVID means less variants,” Eric Lofgren, infectious disease professor and epidemiologist at WSU, said. “The less people who are sick, the less people have SARS-CoV-2, the less mutations in spike proteins, so our ability to reduce that number is important for getting this under control.”

All three “variants of concern” identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have been detected in Washington. The U.K. variant is the most common, with at least 100 confirmed cases of that variant in nine counties as of March 12, including a case confirmed in Spokane County as well as one in Benton County. This variant has health officials concerned due to its tendency to be more contagious.

There have been five confirmed cases of the South African variant as of March 11 and one case of the Brazilian variant, P.1, all confirmed in King County.

These variants are even more concerning because they might diminish the effectiveness of antibodies produced by vaccines, although research is underway to determine how much.

As optimistic as we might feel, now is not time to let down our guard. It’s not clear yet how well the vaccines will do against these new coronavirus variants, and if one or more takes hold, increased hospitalizations and deaths might follow. Health officials urge us not to rush too fast to reopen everything, and to keep wearing our masks.

“The worst thing that can happen is what just happened in Idaho, not learning the lesson of when the numbers go down, you don’t open things up again,” Palmer said.

As of March 12, Idaho’s rate of COVID deaths per capita far outpaces Washington’s, with 106 deaths per 100,000 people versus 67 per 100,000 in Washington, according to the CDC.

The Delay

The number of people who want the COVID-19 vaccine far outnumbers the doses available to states each week, and state health officials can do little more than repeat their weekly allocations to residents.

Every week providers get fewer doses than they requested or in some cases no doses at all. This has created a constant game of hurry up, wait and then vaccinate like crazy, leading to quick pivot actions, like CHAS partnering with Gonzaga to get an unexpected shipment from the federal government into the arms of more than 7,000 people in about a week.

The Biden administration has promised enough doses for every eligible American by the end of May, and while distribution of these doses will continue well into summer, questions linger about what is taking manufacturers so long.

The reason Biden can even promise hundreds of millions of doses by early summer is to some extend a result of the U.S. government’s spending power.

The pharmaceutical industry became more responsive to the current emergency in many ways, said Andy Stergachis, a pharmacy and global health professor at the University of Washington. Several firms have teamed up, such as Pfizer and BioNTech joining forces to make a single vaccine, and now Novartis has agreed to help produce it in their facilities.

“(Pharmaceutical companies) are getting the push-pulls, including from the government, which is setting up incentives and stimulating with funding and advance purchase commitments,” Stergachis said.

“Now what we’re realizing is there have been bumps in the road, and they are characterized in a number of ways: manufacturing delays, shortages of raw materials and also the reality that these newish technologies are being scaled up at an industrial scale,” he said.

The result has been way more demand than supply for the first three months of vaccine distribution. Even in recent weeks, hospitals, clinics and health districts ordering vaccine doses are not receiving the amounts they request. In early March, providers would order more than 400,000 doses, but the state was only receiving a supply of about 300,000 or so per week.

Beyond that, the Department of Health is only tapping into a fraction of the available providers statewide who could distribute vaccine due to supply limitations. Of the nearly 1,400 providers that have signed up to distribute vaccines, only about 300 of those providers have received doses consistently thus far.

On Herd Immunity

Public health experts have tossed around the possibility of achieving herd immunity – the critical mass of immunized people needed to tamp down a virus – this summer and spring, but they don’t all agree.

While Shah wants 70% of the state’s eligible residents to be vaccinated by the fall, herd immunity locally will likely look different in each community.

“Spokane will be different from Pullman, and Seattle will be different from the West Coast,” Lofgren said.

Palmer points to specific thresholds in different populations but said that pinpointing exact percentages is a “fool’s game” because it is something you can only know once you’ve seen it.

Research is ongoing to see how long a person will have natural immunity after recovering from COVID-19 and how long vaccines are effective. Clinical trials for all three vaccines will continue well into 2021 to track participants in search of these exact findings. Answers to these research questions will help inform what herd immunity could look like.

With nearly a third of U.S. residents testing positive for COVID-19 in the past year, natural immunity might play a big role in bridging the gap to summer when there are enough vaccines for all adults.

“How (natural and vaccine-derived immunity) will collide and give us a threshold, that’s really going to be a dynamic situation, and we’ll see that unfold this spring,” Palmer said.

Some experts project we could achieve national herd immunity of about 75%, possibly by this summer.

By May, if 50% of the adult population nationwide is fully vaccinated, with the 20% or so by that point that have natural immunity after an infection, total herd immunity would be close to 75%. Even better would be pushing the total number of vaccinated adults to 75% and then letting natural immunity of about 10% help make up the rest of that difference, said David Line, director of the public health program at Eastern Washington University.

The wild card when it comes to herd immunity is young people. People under the age of 18 make up 21% of Washington’s total population, and while young children have not been infected at high rates, teenagers can contract and spread the virus just like young adults.

Currently, only the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine could reach some of this population, as it is approved for people 16 and older.

Vaccine trials are underway in kids and teens, and Line expects the vaccines to be approved for young people this summer.

“While there are all sorts of difference between an 8- and a 15-year-old, I think the biological differences won’t matter,” Line said.

Approved vaccines for young people might mean the push doesn’t end in May or June but continues all summer long to get kids shots before returning to classrooms in the fall.

As life returns to little pockets of normal for people who have been fully vaccinated, it’s vital to understand the primary goal of vaccination: to prevent severe disease, hospitalization and death.

All three vaccines make good on this goal, according to trial data, but there is a possible caveat.

Even with a vaccine, it is still possible to contract COVID-19, including variants that might make antibodies produced from vaccination less effective.

“You want to prevent infections, but that’s not what the goal is,” Palmer said. “The goal is to prevent these severe consequences.”

How to: vaccine

If vaccine development felt speedy, that’s because it was. But that speed did not cost scientists accuracy.

The mRNA vaccines – Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna – were the first to finish clinical trials in less than a year because they were already being tested for use against other viruses.

A lot of people think the mRNA vaccine technology is brand new, Dr. Deborah Fuller, vaccinologist at the University of Washington, said, but that’s just not the case.

“One of the things a lot of people aren’t aware of is they’ve been in development for 30 years,” she said. “It’s not something we pulled out of a hat.”

Companies had already been conducting clinical trials of mRNA vaccines with different infectious diseases when SARS-CoV-2 appeared. Scientists just plugged in the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 into their mRNA technology and started producing vaccines in a lightning-speed way.

The mRNA vaccines essentially give your cells the blueprint for how to make a spike protein like the one SARS-CoV-2 uses to infect you. Your immune cells do a trial run when they see the protein and mount an immune response to it and create antibodies. This is why you might feel under the weather, especially after a second dose.

In a way, the pandemic is the first trial run for the new technology, but safety trials and how the technology has been developed has taken decades. Fuller said mRNA technology is faster than typical vaccine development technology, which before 2020 could take four years or more.

The speed, she said, should not be translated to cause concern about safety, however.

“I think we’re going to find that while mRNA vaccines are new, they are some of the safest vaccines out there,” Fuller said. “Other vaccines have to use the pathogen themselves. (But with mRNA vaccines) you don’t even have to have a virus, there’s no virus involved.”

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses slightly different technology that achieves the same result as the mRNA vaccines. It is a viral vector vaccine, which uses a harmless virus as a vector to enter your cells and create the spike protein.

From there, the body responds the same as it does with mRNA vaccines, triggering an immune response to get rid of that harmless spike protein and teach your immune system to recognize it in the future in case you come into contact with SARS-CoV-2.

The effectiveness of all three COVID-19 vaccines is incredibly high, and frankly, lucky, Fuller said.

All three COVID-19 vaccines are incredibly effective at 85% or more against severe disease, which is significantly better than the average flu shot, which reduces flu illness in 40% to 60% of people in a given flu season.

‘Don’t hesitate, vaccinate’

With the high demand for vaccine doses in Washington, it can be hard to tell how many people are hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Some clinicians are anticipating these conversations, however, and are advocating for realistic expectations.

Dr. Gretchen LaSalle, a primary care clinician at MultiCare Rockwood and vaccine science fellow, says that public health officials and clinicians should talk to patients about how they might react after a first or second dose.

Current data show it is common to have soreness or redness in the arm after one dose.

After the second dose, it is common for a person to experience flu-like symptoms, like a fever, body aches, or fatigue for up to 72 hours. This is actually a good sign, LaSalle said, of your body producing a robust immune response to the virus. So far, these more dramatic responses have been seen in young people.

“We know after the second dose, it’s more common for people to feel achy and under the weather, and we need to be honest about that,” LaSalle said.

The Food and Drug Administration has set specific guidelines for people with previous allergic reactions to vaccines, including longer observation periods after vaccination and options for second dose alternatives (like taking a different vaccine altogether about a month later) if necessary.

Adverse reactions are possible but very rare so far. During a one-week period early in vaccine distribution, the CDC confirmed 21 cases of severe allergic reactions among the 1.8 million doses given of the Pfizer vaccine. Similarly, during a three-week period in December and January, the CDC confirmed 10 severe allergic reactions to the Moderna vaccine of the 4.04 million doses given in that time frame.

In general, reactions to all vaccines occur within six weeks, LaSalle said.

In the Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech and Johnson & Johnson trials, patients are continuing to be monitored for adverse reactions and their immunity far beyond two weeks postvaccination. These clinical trials are the key to informing researchers exactly what the risks could be for the public down the line.

“There’s a whole cohort of people who are way ahead of population to see how durable these immune responses there are,” Fuller said.

The FDA has not recalled or paused use of any of the vaccines due to adverse events thus far.

So while adverse reactions are possible, the alternative, a COVID-19 infection, cannot only become severe and lead to hospitalization or death, it can also linger. Many long-hauler COVID patients continue to suffer from symptoms ranging from chronic fatigue and brain fog to heart irregularities and lung function. Research is ongoing for these patients as is treatment for them .

“What I worry about is what we don’t know about the illness versus what we don’t know about the vaccine,” LaSalle said.

The next three months

Despite the good news of fans being able to attend the Seattle Mariners’ opening day at T-Mobile Park, public health officials struck a note of concern in early March.

“We’re moving into a new era of this pandemic,” acting State Health Officer Dr. Scott Lindquist told reporters March 11. “While I initially thought it would be this gradual phase out and the virus goes away, it’s not unrolling that way.”

He warned that with case counts plateauing – no longer declining – and with more variant cases confirmed each week that the state could be headed toward a fourth wave.

If people continue to hunker down and keep disease transmission low while vaccines become the predominant source of immunity in the state, there’s also the chance for a more normal-feeling summer.

A summer surge might be inevitable in very warm parts of the country, Line said, where people are inclined to go indoors and enjoy air conditioning.

“I do anticipate there will be a surge, and it will be a minor one by all standards in locations where it’s hot,” he said.

COVID-19 will not be eradicated by fall.

Line points out that the Spanish flu was around for a decade after its deadly debut in 1918.

This means things like testing, contact tracing and isolating will likely be necessary at least through the end of the year and probably longer. Some experts worry about a surge of cases in the fall, if the novel coronavirus reverts to similar seasonal patterns of other coronaviruses, which crop up simultaneously with flu season.

Research continues to investigate the timing of needed booster shots to continue immunity as well as fight off new variants of the virus. Both Moderna and Pfizer are developing and testing booster shots.

What’s clear to experts statewide is that the next few months are nothing short of critical.

“A lot of this is still under our control, vaccine canvassing is easier when less people are getting sick,” Lofgren said.

That said, now is not the time to relax.

“It’s been strange to me to see people talking about the end of the pandemic, when we’re actually at its peak right now,” Lofgren said in February.

The outcome of what summer and fall of 2021 will look like and exactly how “normal” life might be will largely depend on our willingness to not gather in large groups, wear masks and continue to participate in isolation and contact tracing.

Doing not quite enough now to keep case counts down could lead to the possibility of a kind of pandemic purgatory.

“The place we don’t want to get to is where vaccines are just good enough and the variants are just prevalent enough, and it’s something you have to live with now,” Lofgren said. “Every time you go to a concert you have to weigh the risk.”

The outcome of this spring’s vaccination effort, one that has not been attempted in the United States in more than 50 years, is still up for determination.

LaSalle thinks that by late summer the majority of people who want to be vaccinated will have had an opportunity, but whether that will be enough to tamp down the virus remains to be seen.

“If not enough people want to be vaccinated,” she said, “we’re still going to be in trouble.”