In Bachfest concert, cellist Zuill Bailey and guitarist Jason Vieaux create the sound of symbiosis

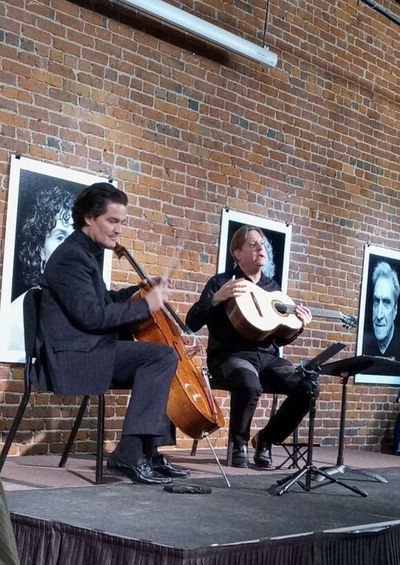

Joining Artistic Director Zuill Bailey at Barrister Winery for the latest program of the Northwest Bachfest last Saturday and Sunday was Jason Vieaux, classical guitarist.

Before performing, Vieaux spoke to the audience with great sincerity and modesty, expressing his appreciation for the opportunity to appear in Spokane and his good fortune at having formed a friendship with Bailey. All modesty aside, Vieaux is a distinguished musician and teacher, having founded the guitar department at the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and having taught at the Cleveland Institute of Music for 25 years. He also has a Grammy to his credit, awarded in 2015 for his album, “Play,” as best classical instrumental solo.

Vieaux’s manner of speaking – clear, thoughtful and fluent – was mirrored in his playing of Domenico Scarlatti’s “Sonata in A major.” Composed originally for harpsichord and transcribed for guitar by Leo Brouwer, the piece gave us our first view of one of Vieaux’s outstanding attributes as a guitarist: his ability to voice several simultaneous melodic lines with complete independence, imparting subtle shadings of tone and phrasing to each one. While Scarlatti’s music is usually performed as relentlessly buoyant and cheerful, Vieaux found recesses of meditative calm, and sometimes melancholy, amidst the intricate counterpoint.

Vieaux’s program was thoughtfully curated, and spoke to the breadth of his taste: from Scarlatti and Bach in the early 18th century, to compositions of the present day by Vieaux himself and his colleagues. Throughout, Vieaux maintained extraordinary focus on the minutest details of execution, carefully adjusting the distance of his right hand from the bridge of the guitar, to produce subtle differences in timbre as suited the demands of each phrase.

Every piece, from the exquisitely refined “Violin Sonata No 1 in G minor” of J.S. Bach to the ambiguous harmonies and dark intimations of Pat Matheny’s “Road to the Sun,” was bathed in the same bright, even sunlight of Vieaux’s interpretive character. This may have led some listener to the only criticism possible of his playing on that evening, which was a certain uniformity, rather than sharp differentiation of style among composers of very different natures.

Anyone who held that objection on Saturday would have hastily jettisoned it on Sunday afternoon, when Vieaux was joined by Bailey in a concert at which the programming was as spontaneous and impactful as the performances. The essential difference between the two concerts can be summed up in a single word: synergy. There was first the synergy between the players and their audience, which was twice the size of the crowd that showed up on Saturday night, and strained the capacity of Barrister Winery. A sold-out house always creates an air of intense expectancy, and this was no exception.

The second source of synergy was, of course, between the two artists: Vieaux, the more (superficially) temperate and self-contained, and Bailey, the more volatile and spontaneous (again, superficially; he is secretly obsessed with detail and a fanatical perfectionist). The crackling expectation in the air combined with the dynamism between the performers to produce a concert to remember – an accelerating ramping up of intensity and communion to the point at which separations between the stage and the seats and between artist and audience dissolved, producing a distillation of pure joy.

The program consisted of a group of works that had mostly been announced in advance and another group announced from the stage. It began with two solo performances by Vieaux, which, while demonstrating the same clarity and control we heard on Saturday, exhibited greater rhythmic flexibility and variety of color. The first was a masterful arrangement by Vieaux himself of Bach’s “First Suite for Solo Cello in G major,” the piece that introduced Bailey to Spokane audiences in March 2012. Next, Vieaux elected to insert a work not mentioned on the program, the “Evocacion” from Juan Merlin’s “Suite del Recuerdo.” This performance exhibited tremendous rhythmic and coloristic vitality, and exemplified the greater expressivity and intense lyricism that characterized Vieaux’s playing from that point forward.

He and Bailey then performed a complex and powerful work by Brazilian composer Radames Gnattali, whose works demand investigation. The audience was held rapt throughout Gnattali’s “Sonata for Cello and Guitar,” save at the conclusion of the central Adagio, when they gasped audibly at the exquisite tenderness and refinement with which Bailey and Vieaux matched the tone of their instruments as they slowly sank into silence.

The rendition of Manuel de Falla’s “Suite Populaire” showed the two players in absolute musical symbiosis. In the popular “Asturiana,” Vieaux never felt the need to glance at the music, but rather kept listening with the fiercest intensity to every detail of his partner’s playing, matching every pause and passionate outburst.

The intensity of the concert rose steadily through a series of works, mostly well known, that were performed with such passionate dedication as to seem improvised on the spot: the “Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5” of Heitor Villa-Lobos, popularized by a recording by Joan Baez in 1969, Fernando Bustamante’s ebullient “Misionera,” which the audience welcomed with an explosion of shouts, Camille Saint-Saens’ serene “Le Cygne,” a new arrangement by Bailey of John Williams’ haunting Theme from “Schindler’s List,” Nicolo Paganini’s Variations on a Theme from Rossini’s “Moses,” and, lastly, Charles Gounod’s heart-easing “Ave Maria.”

One had to hear Bailey’s performance of the Paganini variations to believe it. The work is part masterpiece and part circus trick, in which a series of increasingly demanding variations are performed on a single string – the A string – of the cello, incorporating every trick of fingering and bowing in Paganini’s revolutionary arsenal. Bailey’s cheerful smile as he greeted the thunderous ovation that followed masked the decades of tireless practice required to vanquish the piece with so little apparent effort.