50 years after Sawtooths were protected, new challenges arise. Is Idaho up to them?

As Hannah Fobert crunched along the dirt path of the Grand Mogul trail, she carried a saw taller than she is, with long handles on either side and a guard covering a row of jagged, inch-long teeth. The 6-foot crosscut saw wobbled precariously with each step, but Fobert wouldn’t have to walk much farther.

Before long, Fobert and her hiking companions, Dalton Warr and Henry Vaughan, found a tangle of trees crisscrossed over the trail. They’d spend the next several hours clearing obstacles like these from the path near Redfish Lake, which would make up just a few of the 150 miles the Sawtooth Society cleans up in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area every year.

The U.S. Forest Service, which manages the recreation area, used to handle this work on its own, but with more than 750,000 acres of land and 900 miles of trail, the agency’s ever-shrinking staff can’t keep up. Increasingly, SNRA officials have turned to Idaho nonprofits to help fill in the gaps.

Where once the challenges facing the recreation area were from mining companies, after 50 years, new threats come from within the government agencies tasked with managing it and from the communities and visitors who love it most.

Booming recreation, a changing landscape and a lack of permanent funding will shape the SNRA for years to come.

The SNRA headquarters is about an hour south of Redfish Lake. The log cabin-inspired building garnered controversy when it was constructed in the early days of the SNRA, with Ketchum residents worried the building would damage the environment or attract too many visitors. The building sits on the southeast edge of the area, its wood siding and A-frame peaks blending into a grove of aspen trees.

In early June, area ranger Kirk Flannigan sat at a large wooden conference table there, a line of photo albums spread out across one edge. Like the headquarters itself, the albums tell the history of the place.

Idaho’s elected officials established the Sawtooth National Recreation Area 50 years ago, on Aug. 22, 1972, after a political tug-of-war that lasted just as long. The area, nestled in Central Idaho among the Sawtooth, White Cloud and Boulder mountain ranges, became a recreation area managed by the U.S. Forest Service after efforts to turn it into a national park failed several times.

Old photos in black-and-white and sepia tones show homesteaders, miners, decades of politicians who pushed to protect the area and recreationists – a community that shaped the SNRA. Flannigan is familiar with the power of that community. Today, it’s a patchwork that still holds the area together.

Gesturing his arms widely to indicate the wilderness sprawling out from the headquarters, Flannigan described himself as something of a general manager of the SNRA. He works with the community, signs off on everything from fisheries to fire projects and oversees staff.

When the SNRA was established, it had 40 employees, according to previous Idaho Statesman reporting, including at one point a six-person law enforcement crew and 11 rangers. Millions of dollars were spent on securing private land easements, and hundreds of miles of trails were built. By the late 1980s, as Congress slashed Forest Service funding, staffing wavered and has dwindled ever since.

Flannigan said since the 1990s, the recreation area has had a 60% decrease in staff, with declines sharpest among staff whose roles aren’t wildfire-related. Today it has about 35 employees, many of them shared with the Ketchum Ranger District of the Sawtooth National Forest. Only about 19 employees are considered SNRA “core staff,” and Flannigan said workers often struggle to find places to live in the housing crunches of the Stanley and Wood River Valley communities.

The SNRA still has a full-time trails foreman and small crews made up of seasonal workers on the job from mid-May through October. But they typically address deferred maintenance – infrastructure issues that are becoming more common after decades of use – rather than ongoing maintenance to clear obstacles, cut back brush and mitigate erosion.

“We’re doing repair, reconstruction, realignment, bridge work … bigger projects,” said Susan James, the recreation manager for the SNRA, in an interview. “And then we actually have quite a few different partners that we work with that also help us with trail maintenance.”

A patchwork of nonprofits and other organizations have stepped in, often bringing grant funding and volunteer labor. Because the SNRA has no volunteer or partnership coordinator, managing the collaborations falls to Flannigan, James and other employees.

Partners help the Forest Service handle everything from wildlife to rivers. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes lead the recreation area’s salmon restoration efforts, and in 2011 the Sawtooth Historical and Interpretive Association stepped in to take over educational work at the Redfish Lake Visitor Center that had previously been done by rangers.

For trail maintenance, the Forest Service works with the Sawtooth Society, Pulaski Users Group, Idaho Trails Association, Idaho Conservation League and more. Many of those groups recruit volunteers, who are supervised by trail crew leaders like Fobert, Vaughan and Warr, who worked on Grand Mogul in June. Often, Flannigan said, the Forest Service will direct its own volunteers to the nonprofits, as the agency doesn’t have many opportunities for solo volunteers.

“Without these partners, we’d be in a world of hurt,” James said.

She said some of the partners have become independent enough to tackle a list of trails with minimal oversight. Warr, the Sawtooth Society’s stewardship coordinator, told the Statesman the organization’s goal is to clear the list the Forest Service provides and then address trail user feedback. Typically, the Sawtooth Society clears around 100 miles of trails each summer but Warr said since 2020 – when it cleared a record 163 miles – that number has trended closer to 150.

“All these organizations together are not covering all the miles of trail, even on an annual basis,” Kathryn Grohusky, director of the Sawtooth Society, told the Statesman in an interview. “It’s not like you can just leave (a trail) for 10 years. It’s an annual thing plus a two- to three-year cycle for large work.”

Wildfires, pests and diseases can damage whole stands of trees that later come down in a maze of trunks. Landslides can completely cut off trails, particularly as the recreation area has seen ongoing earthquakes in the last two years. Those projects are more expensive and time-consuming than regular maintenance, and they can throw progress off-course.

“I wouldn’t say that we’re losing any miles of trail,” James said. “We are definitely falling behind on maintaining them, though.”

‘Roller coaster’ budget

The Forest Service manages more than 20 million acres of land in Idaho spread across seven national forests. The SNRA is meant to be the state’s treasure.

“We are supposed to be a showcase for the national forest system,” Flannigan told the Statesman.

Others have called it the “crown jewel” or the “heart and soul” of Idaho.

But for more than half the SNRA’s existence, the Forest Service has endowed fewer and fewer resources to it. SNRA officials did not provide the Statesman with budget figures, but said the area is funded through a mishmash of investments.

Flannigan said annual line-item funds go toward fixed costs – employee salaries, building costs, vehicle maintenance and the like. Funding for recreation, deferred maintenance and other projects largely comes from outside sources, like the Land and Water Conservation Fund, Great American Outdoors Act, the recent President Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill and grants and other agreements.

“I describe it as a roller coaster,” Flannigan said. “One year we’re up, the next year we’re down. But we have typically been flat or down slightly in our budget, and we cannot maintain an adequate staffing level.”

Anywhere from 40% to 60% of the SNRA’s recreation budget every year comes from outside sources, James said. But often those are obligated to be spent on specific projects, like $132,000 from the Great American Outdoors Act that went toward trail and bridge work in the Sawtooth Wilderness and Alice-Toxaway Loop areas last year.

“That creates a little bit of a challenge for us just trying to get our basic maintenance done,” James said.

Unlike national parks, which have line-item budgets but also collect entrance and user fees, the Sawtooth National Recreation Area’s funding isn’t tied to its visitation. A national park like Grand Teton, which is less than half the size of the SNRA, charges $35 per week per vehicle, while the SNRA will see nothing from tourists who drive its roads, hike its trails and use most other amenities outside of campgrounds and some day-use sites and boat ramps.

Even if the recreation area’s funding hinged on visitation, the area doesn’t collect the kind of definitive user data that national parks do.

“Other types of parks that are more tightly protected have entrance stations where you can count how many people come in and out and hand each person a little brochure and tell each person: ‘Guess what? This side of the park is closed because there’s a grizzly bear,’ ” Grohusky said.

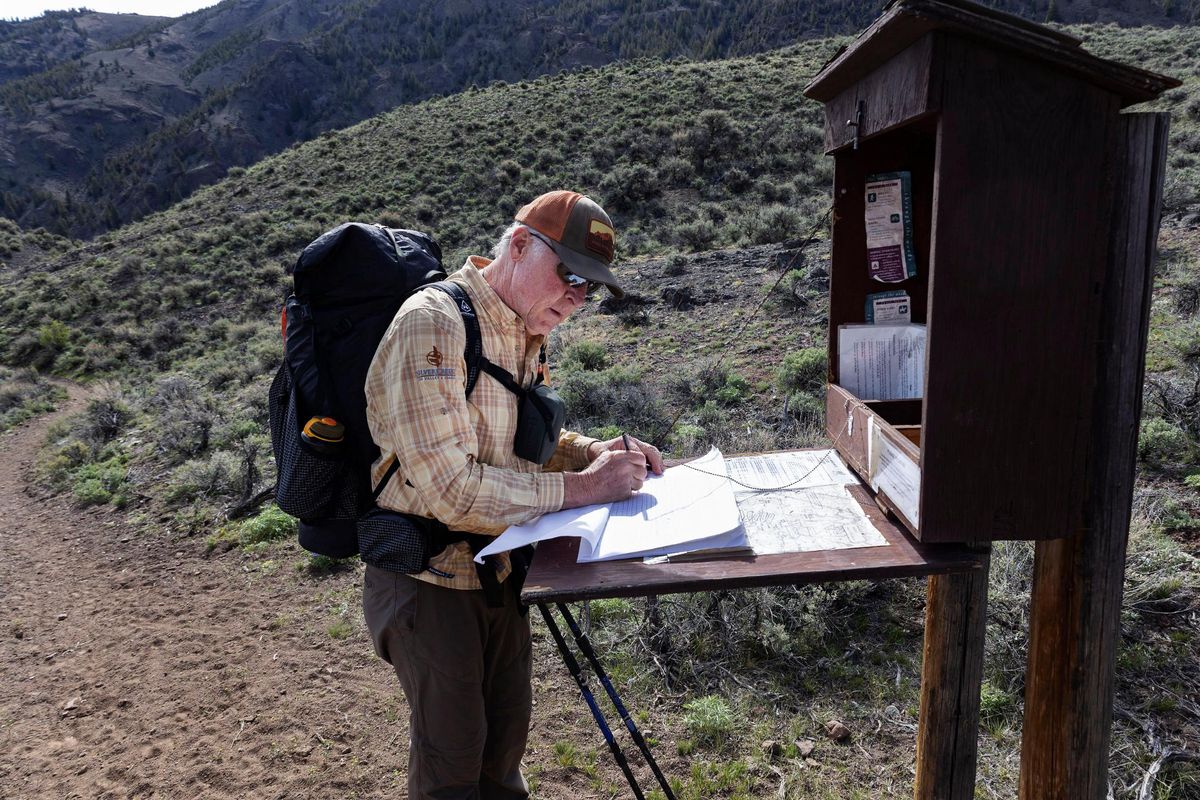

Campground and wilderness permits (which are free but required for the Sawtooth Wilderness) data is reliable, but trailhead registers – check-in stations where users are supposed to sign in on a logbook – aren’t. James said the agency is working on expanding trail monitoring, but the results will represent broad trends, not precise user counts.

“We’re not going to build gates,” Flannigan said. And even potential user fees or other funding sources are up in the air.

In the 1990s, trailheads in the SNRA were part of a fee demonstration program from the Forest Service that charged people $5 to park and hike, with funds going back to recreation spending. The program lasted into the early 2000s but was considered controversial by some, including Idaho’s congressional delegation who voted against the program. Sen. Mike Crapo tried to introduce a bill in 2007 that would bar federal agencies from adding or raising fees as part of the program.

Congress later replaced the fee program with the Recreation Enhancement Act, which allows federal agencies to charge fees on sites that provide certain amenities – including toilets, interpretive signs and security – which most SNRA sites don’t have.

Flannigan said he could see some benefit in leveraging more fees and acknowledged the SNRA staff have discussed the idea of user fees or a permit system for high-use wilderness areas “informally.” At his previous Forest Service post in Oregon’s Deschutes National Forest, he said, fees raised hundreds of thousands of dollars every year for recreation.

Sawtooth area may be nearing capacity

Even without solid data, it’s clear more people than ever are visiting the SNRA. In the mid-1970s, shortly after Congress designated the recreation area, Forest Service officials raised concerns about crowding, the Statesman reported. At the time, the agency estimated trail use was around 20,000 annual visits.

In 2020, the most recent Forest Service visitation estimate available, officials said around 585,000 people visited the SNRA – nearly double the visitation estimate from 2015. James said the estimate confirmed what their staff had witnessed: a huge surge in recreation during the COVID-19 pandemic that showed no signs of slowing.

It’s not just one activity that’s growing in popularity, James said. There has been an increase in day-use activities like hiking, even in more remote locations. Traditional uses like backpacking and horse packing are still happening at high numbers, too.

And camping continues to be a point of contention. For years, people have had issues making campsite reservations, James said, and she frequently hears complaints about the Recreation.gov website used for booking.

“I hear this story every year,” James said. ” ‘I sat there from the minute that campground opened up and pushed the button repeatedly trying to get a reservation.’ “

Flannigan said some of the Redfish Lake-area sites are among the most popular campgrounds in the entire Forest Service system. When summertime sites open up in December, January and February, they sell out in seconds.

James said the SNRA has tried to leave about 60% of sites at its 35 campgrounds as walk-ins to avoid the reservation issues, and officials have discussed the possibility of a lottery for some campsites. Recently, the recreation area decreased the amount of time that campers can stay at a designated dispersed site – areas without amenities like bathrooms and potable water – in an effort to encourage turnover. After 10 days at a site, campers must move at least 30 miles away for the next 30 days.

Despite the popularity of the existing campsites, Flannigan said there are no plans to build new ones. He also doesn’t foresee enlarging parking areas at trailheads, which have become increasingly busy.

“That translates into lots of people in the wilderness, where people should be having opportunities for solitude,” James said.

That goes for wildlife, too. SNRA wildlife biologist Robin Garwood said with climate change shrinking snowpack, winter recreationists are competing with some of the area’s most sensitive species for space. The human traffic can startle animals like mountain goats and wolverines, prompting them to burn precious calories they need to survive the season.

For wolverines, which are being debated for inclusion under Endangered Species Act protections, encroaching recreation has the potential to threaten their existence. Garwood said the elusive animals create burrows in the snow and could be scared into moving their dens or even foregoing reproduction altogether if they’re too stressed by human activity.

The influx also has people like Grohusky, the Sawtooth Society director, worried about carrying capacity – the number of people that can use the area without damaging the environment.

Wilderness rangers and volunteers have been keeping track of how much human waste and how many illegal fire rings they find in the SNRA. They try to educate hikers and backpackers about Leave No Trace, a set of principles that helps reduce human impact on wild areas.

James said she’s especially concerned about the SNRA’s alpine areas, which have fragile ecosystems and limited space for people to bury fecal matter. The Forest Service has started providing “wag bags” – kits people can use to pack out their waste – in some areas of the SNRA.

“We are probably reaching capacity at some of our high mountain lakes,” James said. “I don’t know that we’re there yet. We’re all just trying to keep our head above water.”

Changing character

Idaho’s congressmen created the Sawtooth National Recreation Area as a compromise: It would protect the area without the restrictions a national park would have put on grazing, mining, hunting and other “multi-use” activities that continue there today. Early advocates said that would preserve the area’s character, a directive that has remained a challenge for the Forest Service.

The SNRA contains roughly 23,000 acres of private land, 85% of which have some kind of Forest Service easement dictating regulations to comply with the “natural, scenic, historic, pastoral, and fish and wildlife values” the recreation area protects. Flannigan said one employee devotes half of their time to the easements, which run the gamut from 50-year-old “handshake deals” to more modern, precise agreements.

The easements are meant to keep the rural Western feel of the area, but there are no uniform regulations, and Flannigan said many of the older agreements lack any “teeth” to enforce those covenants.

“The newer ones are very, very, very specific,” he said. “We’ve learned our lesson.”

Many early easements had minimum square footage requirements to prevent landowners from building shacks. Today, the problem veers in the opposite direction – large buildings with modern features that some argue don’t fit the character of the rural West. Without a strong enforcement mechanism, the Forest Service can’t force private landowners to comply with the values.

And while the SNRA had the support of Idaho’s Legislature and congressmen behind it in the 1970s, that political support is flagging today.

Twice during this year’s legislative session, the Idaho House voted against a resolution to honor the 50th anniversary of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, introduced by Rep. Ned Burns, D-Bellevue. Republican lawmakers blasted the resolution as a celebration of federal land management.

“This is not a celebration of the wilderness of the state of Idaho,” said Majority Caucus Chair Megan Blanksma, R-Hammett. “This is a celebration of the federal government’s overreach and management of what should be state lands.”

In lieu of a state resolution, the town of Stanley and Blaine County – which fall within the SNRA – each passed their own commemorative resolutions.

Rep. Mike Simpson may be the area’s strongest legislative advocate – he helped designate two new wilderness areas in the Boulders and White Clouds in 2015.

Education, money are keys to future, advocates say

So much about the Sawtooth National Recreation Area is instantly recognizable: the jagged mountain peaks, the breathtakingly blue water of the alpine lakes, even the khaki and green uniforms Flannigan and the other Forest Service employees don.

But change is coming to the SNRA. Flannigan said the headquarters building, part of the area’s aging infrastructure, is due for an upgrade soon. The new version will fit in with the rural Western landscape, blending modern needs with historic beauty in a way advocates are pushing for as they face the area’s problems.

“There’s no easy solution to any of (the issues), because they all involve a wide array of stakeholders,” Grohusky said.

She hopes to see the Sawtooth Society collaborate with groups like the Sawtooth Interpretive and Historical Association and the Idaho Conservation League to offer more education. Grohusky said she envisions a program, inspired by one in Colorado, that would involve trailhead stewards. They would greet people at the start of a hike and offer advice and information about the area.

The Idaho Conservation League has a similar program in place, with wilderness stewards who hike into the backcountry and educate visitors about human waste disposal, hand out dog leashes and discuss proper campsite and campfire cleanup. Grohusky said trail stewards in national parks give visitors the sense that someone cares about protecting the place.