Jason Momoa prefers to be called a ‘sensitive alpha male’

HONOLULU – You will want to know what it feels like to be pulled by the strong hands of Jason Momoa from the cyan waters of the Pacific and then to flop, into the belly of a canoe, like some recently netted fish. It feels, I can tell you, wonderful.

This was on a paradisiacal morning in mid-July, just off the Western coast of Oahu. From the wing of a bright orange outrigger canoe, Momoa, casual in a sleeveless shirt and striped pants, like a god on holiday, pointed out the beach where he had learned to surf, the reef where his umbilical cord is buried. His father, Joseph Momoa, lay beside him, cradling an enormous conch shell.

“Aloha, what’s up, my boy?” Joseph said.

“What’s up, Pops?” his son answered as the canoe sped through the water. “This is awesome.” In mellow moments like these, I could almost forget the primal horror of sitting in a swimsuit next to a man who often tops most-handsome lists. A waterman in the canoe’s stern gestured toward a cove famous for Galápagos sharks, and then suggested we take a dip. Most days, I avoid shark-infested seas. But Momoa, 45, seemed unconcerned. I jumped in.

Built like a boulder, if boulders had bedroom eyes and smelled of musk and adventure, Momoa is a bruiser with a difference. Though undeniably an action star – he has played an alien, a barbarian, a warlord in “Game of Thrones,” a swordmaster in the “Dune” movies, a superhero who could absolutely crush a freestyle relay in “Aquaman” – he pairs hypermasculinity with surprising sweetness.

“The thing that makes him an interesting actor is his enormous heart and empathy – all in the body of a Trojan god,” Emilia Clarke, who played his bride on the HBO megahit “Game of Thrones,” would later tell me in an email.

Momoa prefers the descriptor “sensitive alpha male.” He knows what he looks like – “a big tough guy,” as he put it. But he prides himself on being in touch with his feelings. “I still am very masculine. But I embrace the feminine side and also feel like I am OK to be vulnerable, that it’s not a weakness.” On the canoe, he wore a pink scrunchie, a signature.

As Momoa tells it, he spent a decade and more convincing Hollywood he belonged. Now he makes his own way, which had brought him back here, within paddling distance from where he was born.

Momoa had returned to Oahu to host the world premiere of his passion project, the ambitious Apple TV+ series “Chief of War.” (The first two episodes dropped Friday; the other seven follow weekly.) Epic in scope and scale, the series centers on Ka’iana (Momoa), a real-life 18th century warrior who witnessed the unification of the Hawaiian islands and the earliest colonial incursions. Very few Hollywood stories set in Hawaii have actually centered on Native Hawaiians. “Chief of War,” as Momoa sees it, is a necessary corrective. “We have our own stories to tell,” he said.

I had come to Oahu to understand why Momoa, who typically plays toughs and tricksters, had pushed so hard to make a serious-minded period drama performed mostly in Ōlelo Hawai’i, a language he does not speak.

As a child, Momoa was raised by a single mother, an artist, amid Iowa corn fields. His mother taught him a love of old movies. “I didn’t watch ‘Conan’ growing up,” he said of the fantasy franchise in which he would later star. “I watched ‘Rear Window’ and ‘Gone With the Wind.’ ”

Still he never imagined becoming an actor. That changed when he was 19, having moved to Oahu to spend some time with his father, a painter and a waterman. Momoa was folding shirts at a surf shop when he heard that “Baywatch Hawaii,” a soft reboot of the David Hasselhoff original, was looking for local actors. Despite a blank-page resume, he was hired, and you can see him in old episodes, sun-kissed and baby-faced, running across the sand.

He didn’t know how to act, not yet, and to this day he remains more of a presence than a transformative performer, but he found that he loved it. “I actually became obsessed, going, ‘Oh my god, I can study life, I can be anything,’ ” he said.

When “Baywatch Hawaii” ended in 2001, Momoa floundered. Agents wouldn’t meet with him; neither would most casting directors.

A few years later, he landed on another show set in Hawaii, the forgettable “North Shore,” and then jumped to “Stargate Atlantis,” where he played a space alien named Ronon Dex. He met Lisa Bonet in those years, and they married and had two children. Momoa also became a stepfather to Zoë Kravitz, Bonet’s daughter from a previous marriage to Lenny Kravitz. (Bonet and Momoa separated in 2020 and divorced, amicably, in 2024.)

“Game of Thrones,” the hit HBO fantasy, should have been his breakout, and in some ways it was. He was unknown to the show’s creators, David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, when he beat out name actors to play Khal Drogo, a nomadic warlord.

“None of them were believable as someone who could lead and inspire an army,” Benioff and Weiss wrote in a joint email. “Momoa was.” He brought warmth and generosity to Drogo and also, they added, “the awareness that he could rip both your arms off.”

His character died at the end of Season 1. Momoa didn’t work for a year after and not by choice. He had been convincing as a warlord. Maybe too convincing.

Determined to make his own work, he founded a production company with writer and actor Robert Homer Mollohan and director Brian Mendoza. Their first movie, the biker noir “Road to Paloma,” got him onto a Sundance series, which led to a Netflix series, “Frontier.”

Then DC Comics put Aquaman’s trident in his hand. In several movies, Momoa plays Arthur Curry, a figure of superhuman strength and agility who speaks for the sea. This was practically typecasting.

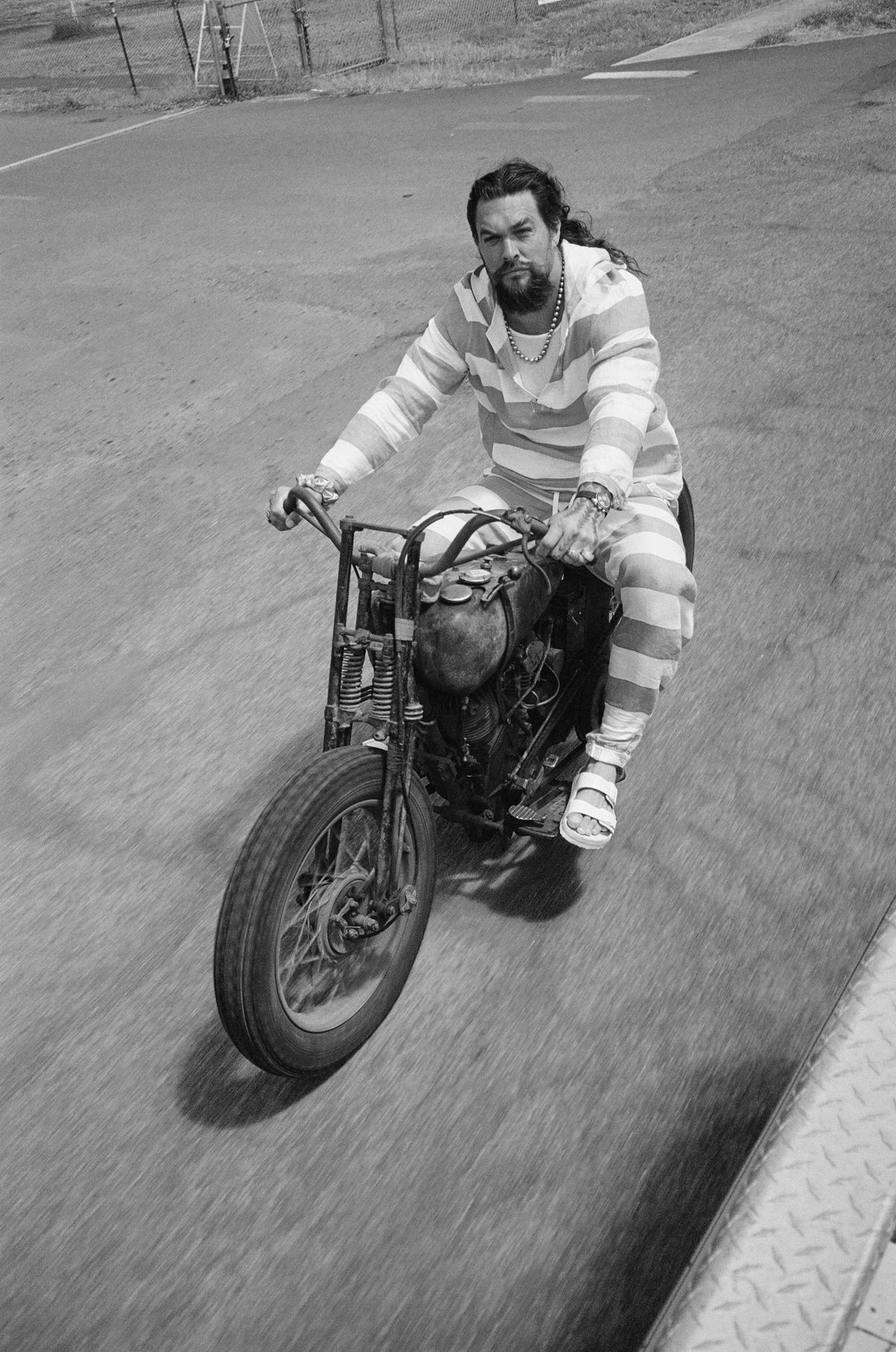

“If this fails, I’m screwed,” he thought at the time. It did not fail. “Aquaman” made more than a billion dollars and burnished Momoa’s reputation as a motorcycle-riding, tomahawk-throwing, heavy metal-worshiping softy.

Certainly, this is how his dearest see him. “He’s a teddy bear,” his daughter, Lola, 18, explained. “He’s just a cave-looking teddy bear.”

Once Momoa had some industry weight of his own, he used it to vary his roles. He hosted “Saturday Night Live,” a longtime dream. He played Garrett Garrison, a washed up gamer in a pink fringed jacket, in “A Minecraft Movie,” a box office sensation that made the elementary school set practically feral with joy. “You’re always big, tough, strong,” Jared Hess, the movie’s director, recalled telling Momoa about the character. “It’s going to be so fun to see you get your butt kicked by a pig.”

Momoa had another, more essential move to make.

Having played fictional superheroes, Momoa would now play a real one in “Chief of War,” a Polynesian one. As Ka’iana, Momoa fights, jokes, schemes and loves. He wallops enemies with a shark-tooth studded weapon, rips out a tongue.

Momoa has a habit of creating found family wherever he goes. And he did that during filming on “Chief of War,” inviting the cast and crew to beach barbecues and house parties.

That was evident on the municipal beach as Momoa moved among his guests, loving and beloved, necking a slightly warm beer.

I saw him again at the premiere, two nights later, on a makeshift stage at a nearby lagoon, introducing “Chief of War” to a crowd of thousands.

“I love you very much,” he told the crowd. “I’m happy to be home.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.