Judge in Seattle blocks Trump order on birthright citizenship nationwide

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown, in office for only a week, calls on a reporter Tuesday at a news conference in Seattle after giving details of a lawsuit against the Trump administration. (Ken Lambert/Seattle Times)

A federal judge in Seattle issued a blistering rebuke to block President Donald Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship.

A lawsuit filed Tuesday in the Western District of Washington came after Trump signed an executive order that claimed a baby born in America must have at least one parent who is either a citizen or a lawful permanent resident to automatically qualify for birthright citizenship.

Trump’s executive order was set to take effect Feb. 19.

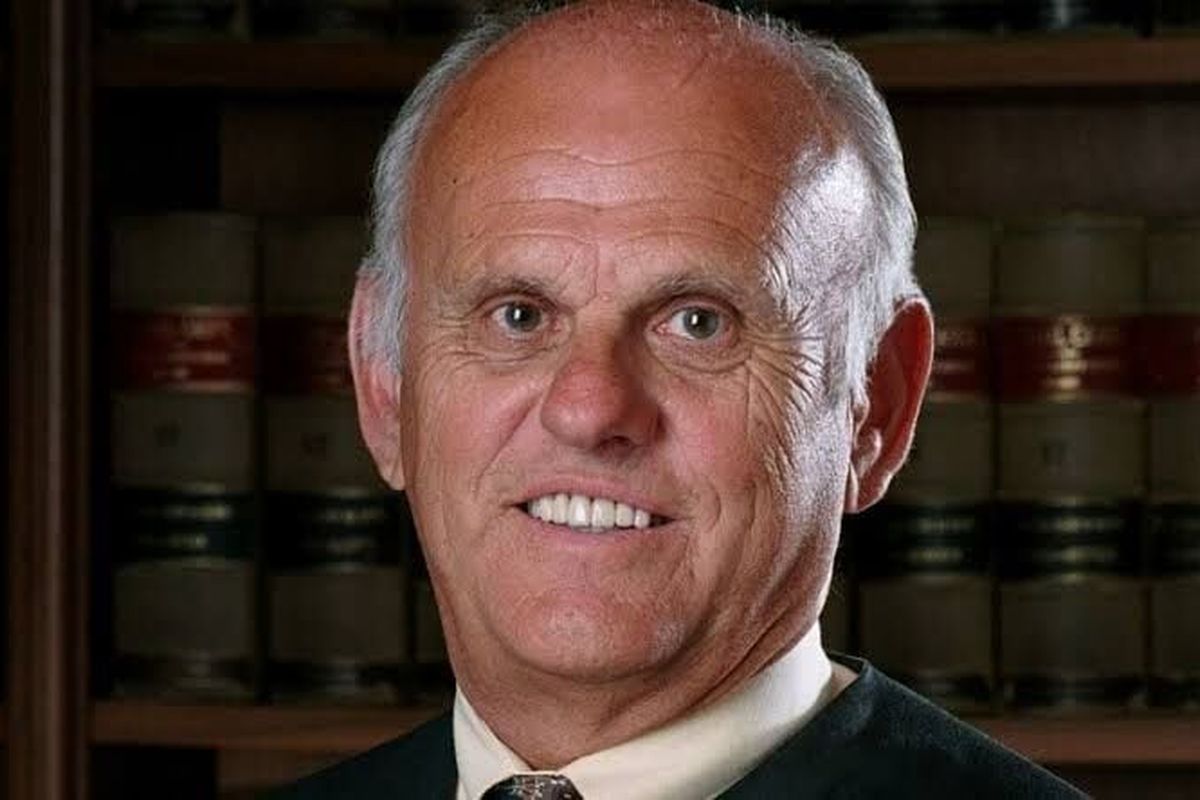

“There’s no surprises with that judge,” Trump said, referring to senior United States District Judge John C. Coughenour.

Coughenour was nominated to the federal bench by President Ronald Reagan in 1981. The judge wrote in the temporary restraining order that there was a “strong likelihood” the states will “succeed on the merits of their claims that the executive order violates the fourteenth amendment and immigration and nationality act,” according to reporting in the Seattle Times.

The Washington State Attorney General’s Office joined Illinois, Oregon and Arizona in the suit that claimed the executive order violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A separate group of 18 states has filed a similar lawsuit in Massachusetts.

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown said the executive order would deny citizenship to 150,000 newborn children every year.

“This unconstitutional and un-American executive order will hopefully never take effect thanks to the actions states are taking on behalf of their residents,” Brown said in a statement Thursday. “Birthright citizenship makes clear that citizenship cannot be conditioned on one’s race, ethnicity or where their parents came from. It’s the law of our nation, recognized by generations of jurists, lawmakers, and presidents, until President Trump’s illegal action. That’s why we’ve stepped in to protect Washingtonians from harm.”

Under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

According to Brown, birthright citizenship dates back more than 150 years, when “our nation had a population of formerly enslaved people who were, in effect, stateless” and has since been affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court to include the children of noncitizens.

The 14th amendment to the constitution, ratified in 1968, overruled the Dred Scott decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which found that the U.S. Constitution did not extend citizenship to decedents of slaves.

“President Trump and the federal government now seek to impose a modern version of Dred Scott,” attorneys for Illinois, Washington, Oregon and Arizona wrote in their request for an executive order. “But nothing in the Constitution grants the President, federal agencies, or anyone else authority to impose conditions on the grant of citizenship to individuals born in the United States.”

According to the Attorney General’s Office, the restraining order means the federal government cannot take action to deny the protections of citizenship to children born in the country while the lawsuit proceeds.

Speaking to reporters outside of a federal courthouse in Seattle, Brown said “we are here thrilled today that the court saw the seriousness and the urgency of the complaint and the request for the temporary restraining order.”

In his comments, Brown said he was “thrilled” the court issued the temporary restraining order to block the “unconstitutional and un-American executive order.”

“This is step one, but to hear the judge from the bench say that in his 40 years as a judge, he had never seen something so blatantly unconstitutional sets the tone for the seriousness of this effort,” Brown said.

The executive order, Brown said, created a “cloud of uncertainty for children being born here in Seattle, all across Washington and all across the country.”

“So, the urgency by which we moved was effective and an appropriate, and supported by the court,” Brown said.

Speaking to reporters from the oval office Thursday afternoon, Trump said lawyers for the federal government would appeal the decision.

“There’s no surprises with that judge,” Trump said, referring to Coughenour.

Coughenour was nominated to the district court by President Ronald Reagan in 1981. In the temporary restraining order, Coughenour wrote there was a “strong likelihood” the states will “succeed on the merits of their claims that the executive order violates the fourteenth amendment and immigration and nationality act.”

Coughenour further wrote the “plaintiff states have also shown that they are likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief.”

As the case works through the federal court system, Brown said he sees “no reason why a court of appeals, or even the United States Supreme Court, would reach a different decision than was reached today.”

As he signed the executive order Monday evening, Trump acknowledged to reporters that the order could face legal challenges, though the newly sworn-in president said birthright citizenship was “ridiculous.”

“We’re the only country in the world that does this with birthright, you know, and it’s just absolutely ridiculous,” Trump said.

Currently, 32 other countries – including Mexico and Canada – guarantee unrestricted birthright citizenship, and an additional 32 countries guarantee birthright citizenship with some restrictions.

The next step in the process, Brown said, will be seeking a preliminary injunction, which he said, “would allow for more thorough briefing.” A preliminary injunction hearing is scheduled for Feb. 6.

Had the court not issued a temporary restraining order, Brown said states would need to begin preparations to institute the policy.

“We had to act now to provide back to the status quo, back to what has been the law of the land for generations, that you are an American citizen if you are born on American soil. Period,” Brown said. “Nothing that a president can do would change that.”