Jules Feiffer and the art of crossing the line

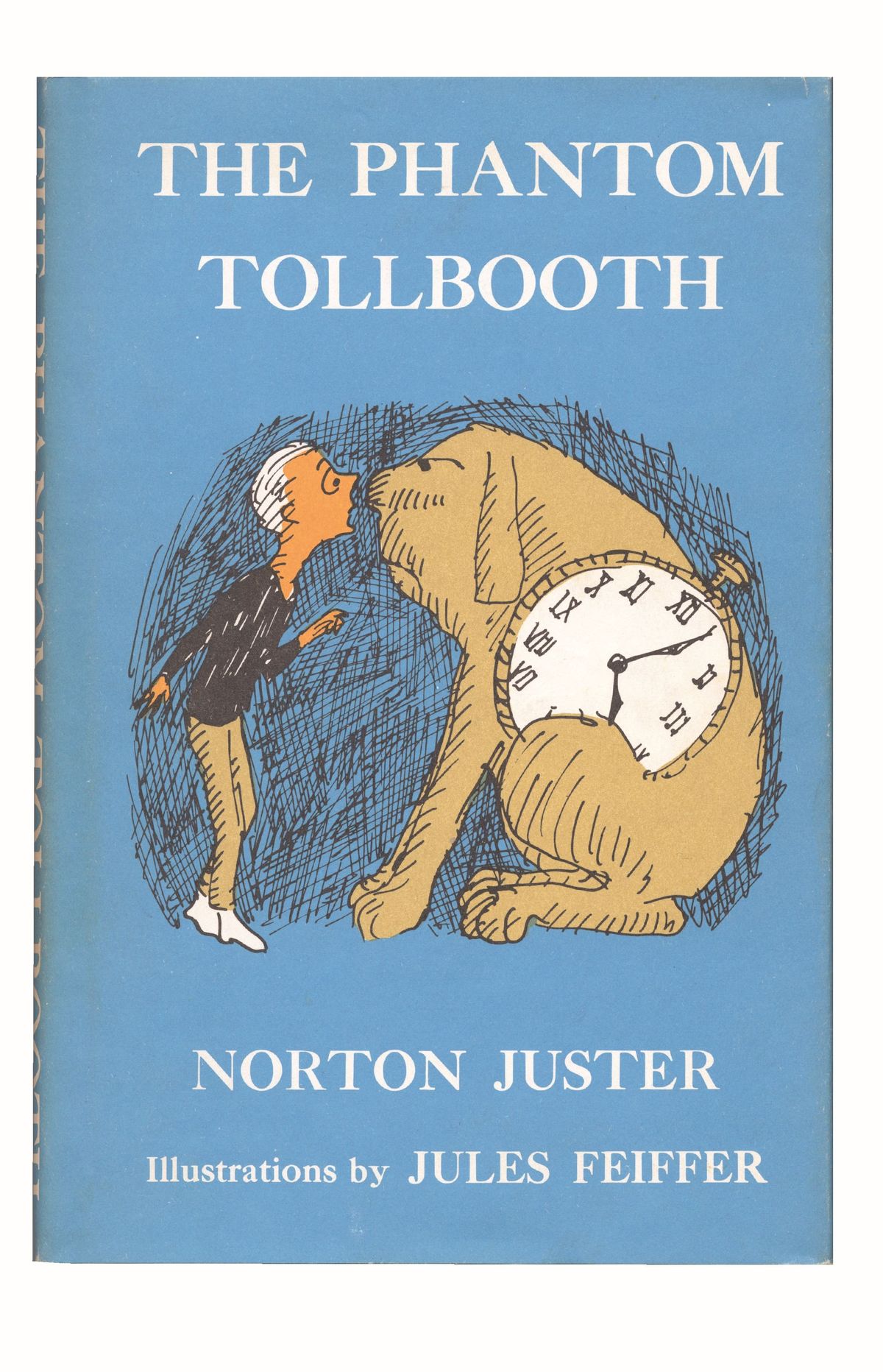

“The Phantom Toolbooth,” published in 1961. (Epstein & Carroll/Abrams Books)

To understand Jules Feiffer the legendary comic mind, one must look to a transformative point in his young adulthood. He didn’t set his early sights on becoming one of America’s greatest satirists. But his powerful creative conscience was sparked by one event and never ebbed across nearly the next eight decades.

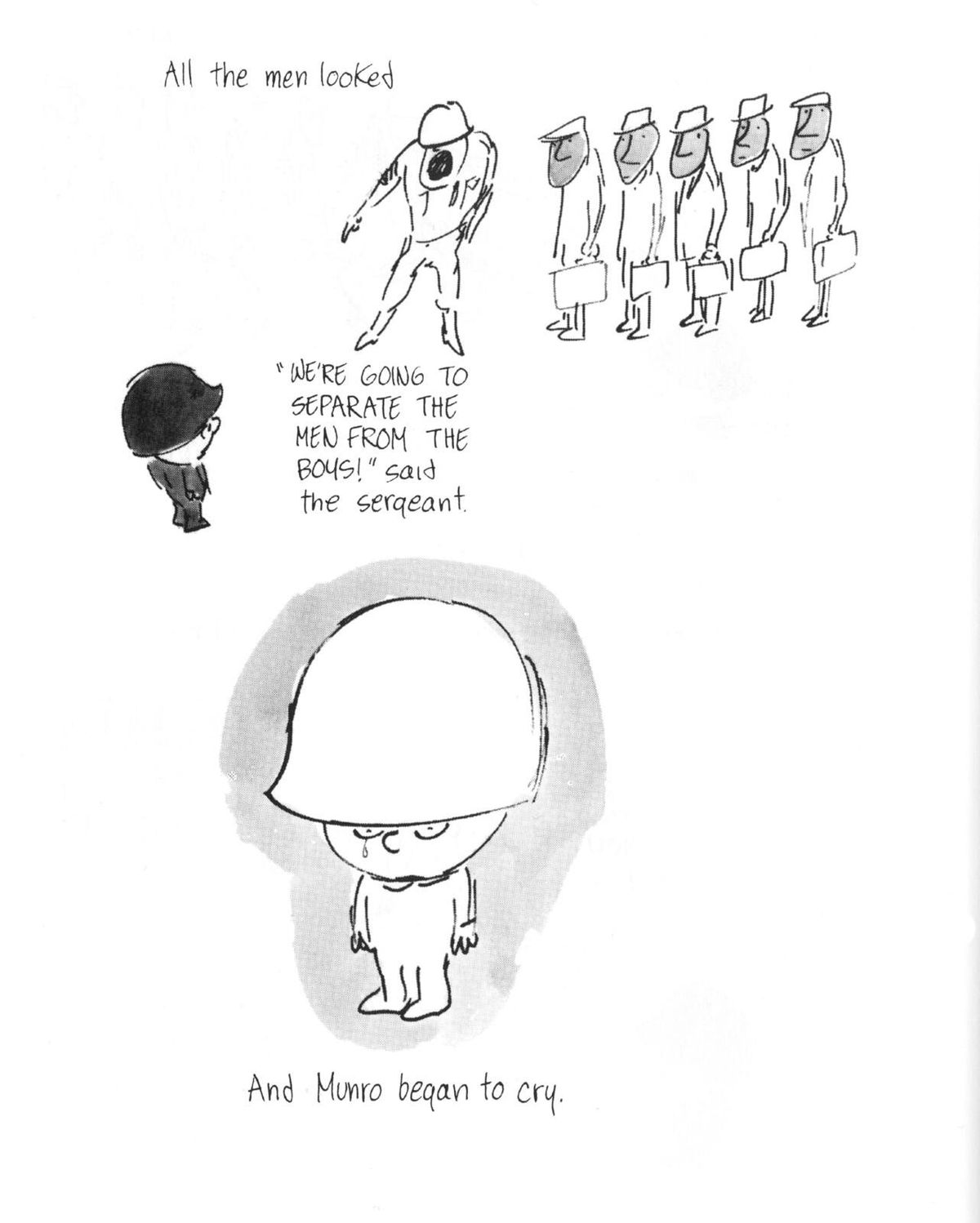

You might best know Feiffer, who died Jan. 17 at 95, as a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist for the Village Voice, or as a screenwriter (“Carnal Knowledge”) or playwright (“Little Murders”) or children’s book illustrator (“The Phantom Tollbooth”) or graphic novelist (“Kill My Mother”). His long, eclectic career took Feiffer far from the purity of the funny pages he first loved.

He told me more than once the government turned him into a lifelong creative commentator with a gimlet eye and an acid-dipped pen – the kind of artistic life appreciated by the Library of Congress, which holds thousands of his artworks.

At a panel I moderated in 2018, he told the room that joining the Army in the ’50s was that formative event because “it made a satirist out of me.” In the military, he encountered what he saw as Cold War conformity, exercises in mind control and McCarthyist sympathies and thought: “These were what I had to cover – what I had to attack.” He said he didn’t want to be molded into a fighting machine.

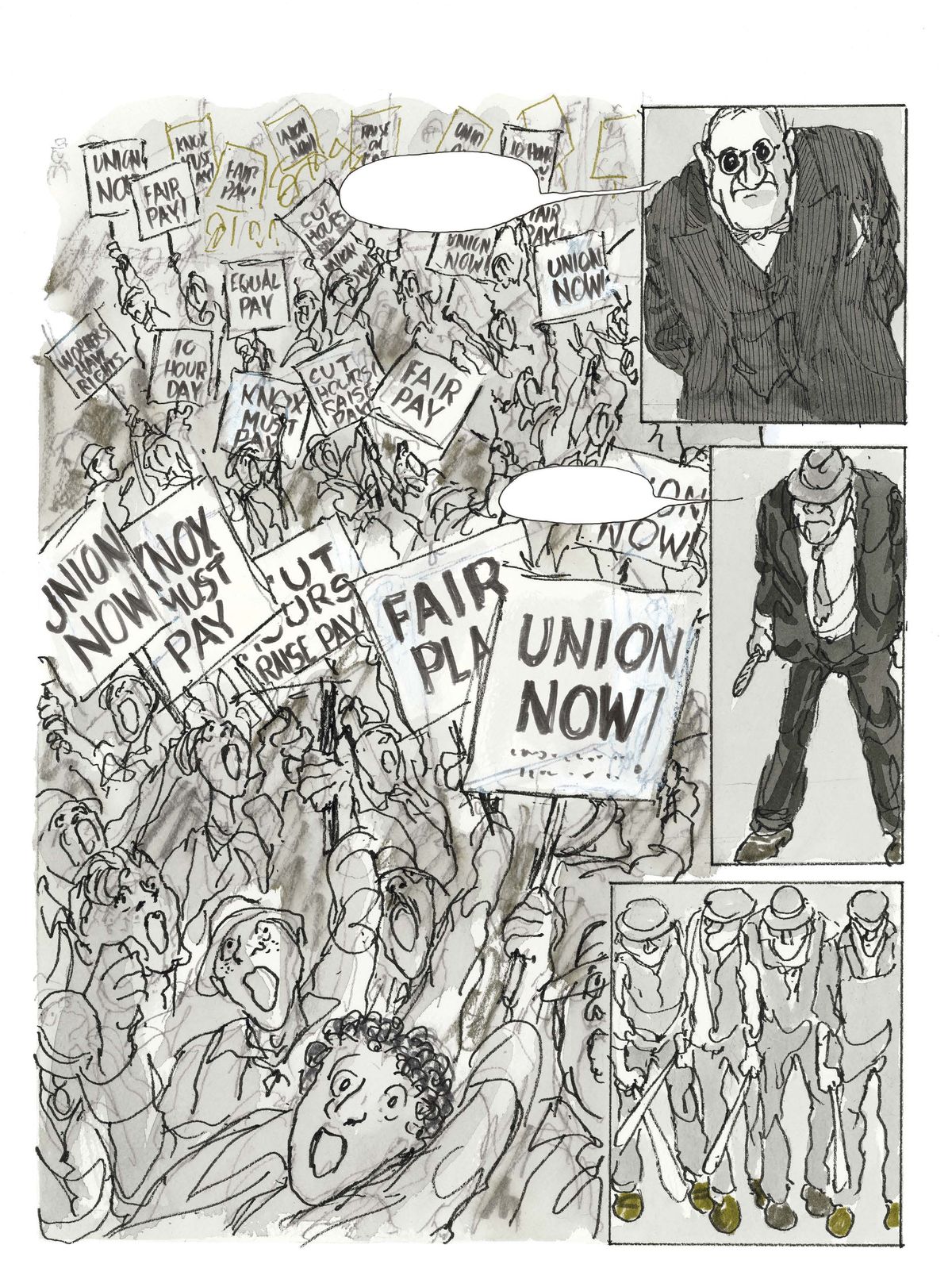

Instead, Feiffer turned himself into a warrior of the word – a kind of conscientious projector, holding up a lens to our social and political ills.

Feiffer saw cartooning as an act of intellectual resistance. He liked to say: “I didn’t want to go into the business of overthrowing the government, but at that time, the government cooperated by giving me a government that needed to be overthrown.”

He also looked around at mid-century America and concluded that so much language was being deployed to obfuscate instead of communicate. “The misuse of language was how we governed,” he said in 2018. “In our families. In our sex lives. In our marital lives. In the country at large. In politics.” On every level, he saw language as a tool too often used to elude and evade, delude and deceive.

That outlook became a through line for much of his work.

In 1971’s “Carnal Knowledge,” for instance, Jack Nicholson’s young lothario character uses words to dance around the truth while also trying to extract information from others. He asks the woman he’s seeing behind his best friend’s back: “Do you always answer a question with a question?” She responds with an equal sense of verbal elusiveness: “Do you always date your best friend’s girlfriend?”

That same year, in a political cartoon, Feiffer drew President Richard M. Nixon in a series of headshots, circuitously saying: “If you think everything your government tells you is a lie – and we know you think that – and we go out of our way to prove to you we’re not lying – are we still lying? Or are we telling the truth? And by now, how would we know?”

Before he felt called to satire, young Jules devoured the Depression-era newspaper comics and dreamed of drawing adventure strips like his artistic hero Milton Caniff (“Terry and the Pirates”). As a boy in the Bronx, he also would render his version of E.C. Segar’s Popeye, many decades before Feiffer wrote the screenplay for Robert Altman’s 1980 film, starring Robin Williams as the fast-talking sailor man. And he doodled his takeoff on the then-new Superman, a character whose personal appeal he explained to me in 2018: “Superman was the assimilation dream of the nerdy Jewish boy who couldn’t get a date.”

Feiffer eventually got his foot in the comics door as a teenager, in the mid-1940s, catching on at Will Eisner’s studio that produced “The Spirit.” Feiffer had one problem, though; unlike the deft stylists such as Jack Kirby surrounding him, he said, he had a line like “coagulated glue.”

No matter how many awards stacked up on his shelf, Feiffer was perpetually humble in his self-assessment.

I’ve never met such a sharp humor writer who for many years, in fact, would downplay that he was much of a writer at all. And he was one of the most free-flowing illustrators I’ve ever known, who, well into his 80s, said his art still didn’t rise to the needs of his narrative storytelling.

Only after I interviewed Feiffer several times, and moderated for him twice at East Coast conventions, did I realize what two elements seemed most central to his staggering creative legacy: He held society to high standards despite perpetual disappointment, and as a storyteller and satirist, he held himself to the same. His withering criticism of both could be unsparing. And that was crucial to his comic genius.

In his latter years, creating noir detective graphic novels became a fresh creative peak that blended his unyielding demands on himself and the world.

On a technical level, he discovered brush pens – a nimble instrument that he vibed with almost organically. At last, he could render in ink what he had only felt free enough to do with his loose pencil lines. He called this stylistic breakthrough “a joy.” When he spoke of that, he lit up like the Chrysler Building, which was completed shortly after his New York birth. That he was still motivated to evolve as an artist into his 80s was a testament to his relentless passion for artistic expression.

Feiffer’s sociopolitical passion also had not ebbed. In his period noir trilogy that begins with “Kill My Mother,” he includes such themes as targeting immigrants for America’s social problems – not an intentionally timely element, he said in 2018, but rather a historical constant going back many decades: “I had to do very little to update it” for contemporary times.

And Feiffer, the self-described liberal intellectual, continued to hold on to hope that the United States would strive to reach its founding ideals. He told the Small Press Expo attendees in Maryland seven years ago: “The excitement is to see what happens next and to see what we can do about the cynicism and untruths we’ve always lived by and justified.”

Always, for himself and society, he wanted language to illuminate. And for him, noir was a creative pinnacle of textual and visual craft. After all, he had spent a lifetime mastering how to bring our world’s coded verbiage and the dialogue of disguise out of the darkness and into the light.