Spokane ‘South Hill rapist’ Coe is released as victims relive their trauma

At the same time the sobs of a woman attacked by the “South Hill rapist” more than 45 years ago echoed through the Spokane County Courthouse, her attacker was getting ready to embrace freedom.

She was there on her 67th birthday, recounting her trauma of the rape all over again, with no legal route to persuade the state of Washington to keep him locked away at the civil commitment facility at McNeil Island. The law is clear: Spokane’s most notorious sex criminal Fred “Kevin” Coe, now 77 years old, would be released from confinement because he is in poor health and no longer deemed a credible threat to society.

The woman, who asked not to be identified because she still fears Coe, directed her comments at him during Thursday’s hearing scheduled to approve his release. But Coe waived his appearance in Thursday’s hearing and didn’t have to show up in person or on video.

“You gave me a life sentence,” the woman said through tears. “The fear will never go away. I was just a young adult, and you destroyed over 40 years of my life.”

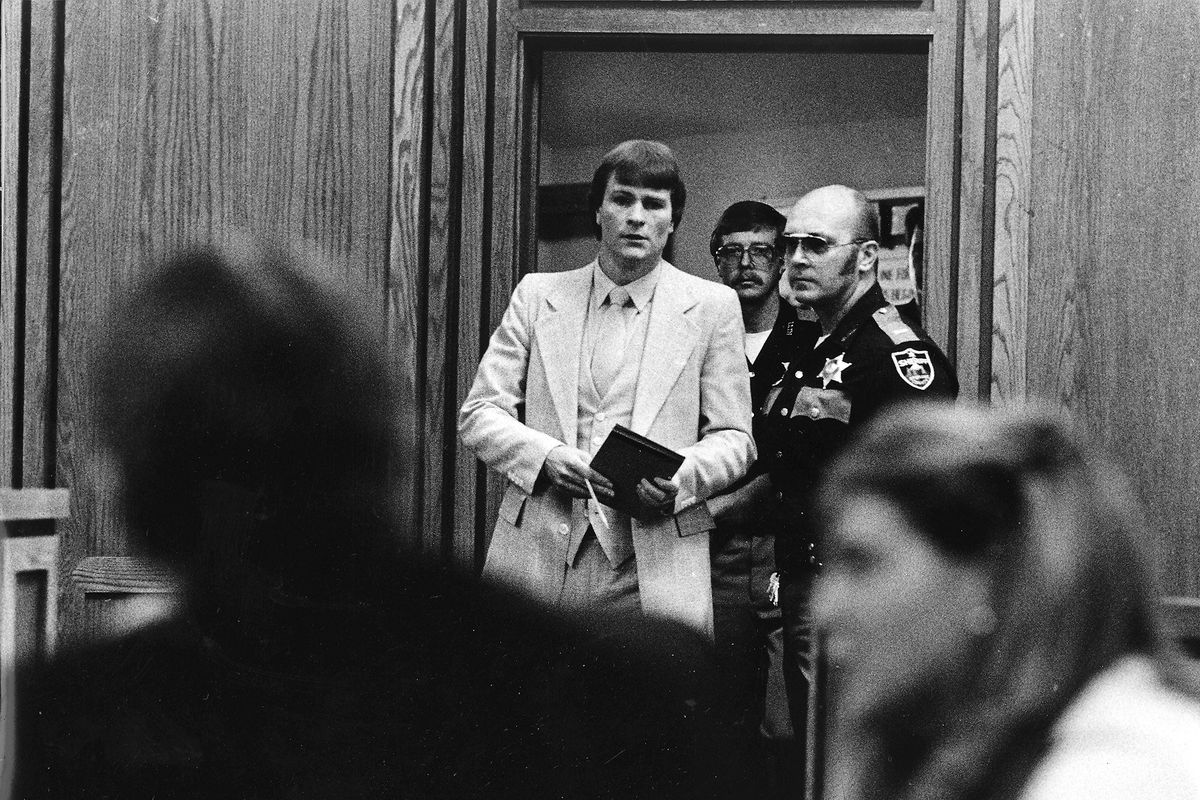

Coe, then in his early 30s, terrorized the city from 1977 to 1981 by raping dozens of teen girls and women on Spokane’s South Hill.

Authorities believe he is responsible for the rapes of as many as 40 people, according to court documents and previous reporting from The Spokesman-Review. Many survivors over the years recounted the same memories of Coe: Smelling like pungent soap, asking them vulgar questions about themselves or their family, shoving a gloved hand down their throat, threatening to kill them if they went to the police, and violently beating them to the point they thought they were going to die.

His hellish stint in Spokane was a dark mark on the city for years – his actions made national news, but for those close to home, they can still recall the fear and uncertainty residents had before his arrest. Attorneys who worked on the trial remember the gumption and passion they had for the rule of law, and police still remember hiding in trees, looking for decoys they had used in an attempt to lure the rapist into their grasp after they noticed a pattern of rapes along local bus routes.

After serving a 25-year sentence at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary, Coe, whose father was the managing editor of the Spokane Chronicle, has spent the past 19 years on McNeil Island after former Attorney General Rob McKenna petitioned to civilly commit him for treatment as a sexually violent predator. In all his time, he has never admitted to raping anyone and has never sought sexual rehabilitation treatment.

Health records say Coe has suffered a stroke, heart failure, dehydration, degenerative disc disease and other ailments. He is described as frail, has withdrawn socially and has little motivation to take care of himself. His decline in health has led doctors to believe he has a low rate of sexual recidivism, making him eligible for release under Washington state law.

Neither the state of Washington nor Coe’s team of attorneys objected to his release. Spokane Superior Court Judge Julie McKay, who recently oversaw Coe’s case, had no way of preventing it.

Coe’s release was made final Thursday – he left McNeil Island, where he had spent his days since 2007, to an adult home in Federal Way. While his time served may be over, the impact on his victims will likely never be.

Survival days

A 15-year-old girl coming back from a Foghat concert decided to take the bus home on Aug. 29, 1980. She’d decided to get off on a stop a couple blocks from her South Hill home when she was suddenly attacked by a man she later identified in a lineup.

The police report listed her attack as occurring at 12:30 p.m. They got it wrong.

“I didn’t get raped at 12:30,” she told the court. “Because as I was lying there being raped, I watched the 12:15 bus go by my house.”

Every day since, she has tried to lessen the amount of “triggers” that have resulted from the attack. The Spokesman-Review generally does not identify victims of sexual assault.

Being back in court brought memories of the many times Coe’s victims were made to repeatedly testify through the years after multiple trials and appeals. It was like living it all over again, they said. Though none of them had to be there, many expressed the feeling that they should be.

“Forty-five years of your life … You go through everything again. It’s a re-rape,” the woman said. “Because when you are raped, the minute you get up and you walk home – your survival days begin.”

Coe never served time for her rape. He was originally convicted of four, but three were overturned after it was discovered multiple witnesses in some of the cases had been hypnotized to help them recover prior memories. Only one case – that of Julie Harmia – withstood those appeals.

In 1980, Harmia, then 27, finished her first day of work at a downtown Spokane jewelry store and took the bus home. Harmia, who has publicly discussed her attack, started walking down 22nd Avenue and Rebecca Street when she saw a man crouch down behind an RV. That’s when he attacked her, covered her mouth with his gloved hand, dragged her into a vacant lot and asked her vulgar questions about her sex life. He made sure Harmia couldn’t see what he looked like by pulling her hair over her face. But because a passing car’s headlights illuminated his face, she was able to properly identify him to police.

Eight people would go on to identify Coe in a lineup during his string of attacks.

Similar experiences plague Coe’s other alleged victims, many of whom were jogging, returning home from work or getting off the bus. It’s led them to have violent flashbacks of the attacks, which some spoke of during Thursday’s hearing.

“I have trouble talking to men in particular. I have very little trust in humanity or human beings,” the 67-year-old said. “You have made me a shell, with nothing inside me but darkness … You beat me up. You made me answer questions about my family, my child, and then you threatened to kill me and my family if I turned you in.”

She was raped at 19 years old in 1978 near Northwest Boulevard while walking home from a restaurant, according to previous reporting from The Spokesman-Review. After the attack, she could only sleep during the day, could only go outside with her dog, and her marriage began to fall apart. A jury acquitted Coe of her rape in 1981. Some women recalled the gossip when people saw Coe for the first time – that “such a good-looking man” could never commit such a crime. For them, it was a slap in the face.

“How dare you breathe the air we breathe?” she said Thursday, speaking to Coe. “It’s not fair. That is not fair to me … You take up space, space that you don’t need. Space that you are not supposed to have.”

She acknowledged she still felt like a victim. She will continue to close her curtains and look over her shoulder, in fear that Coe may come back for her, she said. If he ever does, she will have “to become a survivor.”

After she left the podium, she began to sob uncontrollably. The woman Coe attacked when she was only 15 years old was sitting nearby and stood up to hug her.

“You’re a survivor,” a man told her as she stood in the middle of the courtroom’s gallery. “You are.”

Another woman decided she had forgiven Coe. She was raped in the summer of 1980, a Friday night that forever changed her life.

“I was a victim of a violent rape perpetrated by Fred Harlan Kevin Coe,” she told the court. “As I headed home to shower … I remember crying out to father God, asking him to forgive the man.”

The act of forgiveness “unlocked” the chains that had her bound to the rape, she told the court. It freed her to live a life differently than what she expected. Maybe he needs God, she suggested – maybe like “all of us do.”

Former TV journalist Shelly Monahan-Cain, who was brutally attacked outside the KJRB radio station on the South Hill in 1979, has believed Coe was her attacker all these years based on a letter she received before the rape and a threatening call from prison following Coe’s conviction. Monahan-Cain, who has publicly discussed her attack, on Thursday was also in the courtroom, in which she described lying in the dirt after the rapist beat her so badly he broke bones in her face.

At the time, she turned over, looked up and tried to focus on a single star in the sky.

“I started praying to God,” Monahan-Cain said. “I asked him to please let me live.”

The future

Many survivors of Coe’s time in Spokane suggested writing letters to legislators or expressing contempt for the judicial system letting Coe leave McNeil Island. Under Washington law, the state has to continually meet a burden of proof showing Coe is likely to commit acts of sexual violence if he’s released. There’s little chance they’d be able to do that given his poor health, according to court records.

Spokane County Deputy Prosecutor Preston McCollam was so struck by the idea Coe would be released he convened a team to go through every health report and court record, he said. He was convinced there would be a loophole somewhere to prevent Coe’s victims from having to relive their trauma in court once again. But as he investigated further, he concluded the attorney general’s office didn’t err in its decision, he said outside the courtroom Thursday.

McCollam pulled the group of women who spoke aside into a nearby jury room and expressed his sorrow for what they went through. He also expressed his frustration with how “defendant-centric rights” often overrule the rights of the victim. He suggested a better process under Washington law to notify victims their attacker would be released from custody, like specifying the timing of the notification, how it’s conducted and possibly tweaking its format.

“In this situation, he is released without ever acknowledging guilt or ever completing treatment,” McCollam said. “I personally believe unless he changes his ways … he will spend an eternity surrounded by flames.”

It’s a solemn reminder that every judicial official’s “hands were tied,” McCollam said, because it’s a civil case, not a criminal one. Victim statements were not a requirement for the hearing because it’s a civil matter, but McKay determined they should be allowed. She said, however, that she was concerned allowing the statements would falsely lead the public to believe the testimony could change the outcome.

“I don’t want to cause any more harm and trauma … to cause them to think the judicial system doesn’t care,” McKay said.

Following their statements to the court, victim advocates, media and McKay all appeared emotional, some wiping tears from their eyes.

“While your statements don’t have impact on the proceeding, I will leave here with a hole in my stomach and a hurt heart,” McKay told the women. “Those words have an impact on me personally.”

Coe left McNeil Island at noon Thursday, according to the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. He is expected to receive 24-hour care at his new living facility, a small, light yellow home in a Federal Way neighborhood.

Neighbors of the Federal Way facility who The Spokesman-Review talked to Thursday seemed unaware of who would be moving into the home.

Christine Harris, who was walking her 10-year-old terrier, Tango, across the street shortly after 1 p.m., said the neighborhood has been a “fairly quiet” place in the five years she’s lived there.

“We don’t really see a lot of people out,” Harris said.

Harris and her husband, Daryl, said that their children are grown and do not live with them, “which makes it less of a concern”; however, there are kids in the neighborhood.”

When Coe last interviewed with The Spokesman-Review from prison in 2006, he was intent on clearing his name – he produced multiple excuses he said show his innocence, like instances of sperm motility or a smear-job by the police department. Coe claimed towards the end of his prison sentence he was simply trying to help investigators capture “the real South Hill rapist” by following bus routes as part of a civic promotion business he created with his father.

None of it held up, and he remained imprisoned .

“I wish I could have done this years ago. But it has been many years … I have seen more and know more, and I can sure as hell say more,” one survivor said Thursday of talking about Coe. “… And I wish you were dead.”

But Monahan-Cain believes that, through forgiveness, she is free. And she said it won’t be the same for Coe, who was never convicted of her rape.

“He will never be free,” she said. “I would ask those still hurting … To remember you are a survivor. Jesus is with you. And with that in your life, Satan will never win. The same is with Fred Coe – he will never win.”

Reporter Mitchell Roland contributed to this story.