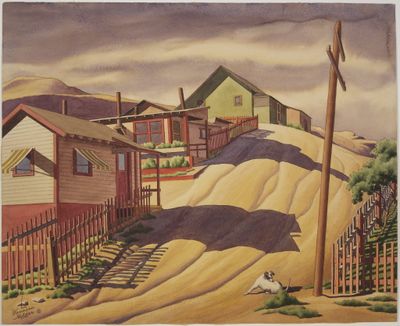

Depression impressions

New MAC exhibit offers a glimpse of our region’s brief Golden Age of art, and how it came to be during The Great Depression

The Great Depression was mostly a downcast, gray period – yet for Spokane’s art scene, it was a glorious, yet brief, Golden Age.

From 1938 to 1942, a collection of young, talented, energetic artists poured into Spokane to teach art to tens of thousands of adults and children. These artists constituted a Bohemian mini-enclave right in the middle of downtown.

In the meantime, they produced work that would make its mark in Northwest art history – and on national art history.

And it was all because of the Spokane Art Center, a jobs-and-culture project funded by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

A new exhibit at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture (MAC) titled “Art and the People: The Spokane Art Center and the Great Depression” shows off some of that work – and tells the story of the Spokane Art Center.

It was, in essence, a jobs program for artists.

“Roosevelt’s first focus was to create jobs for farmers and laborers,” said Ben Mitchell, the MAC curator of this exhibit. “But he also recognized the need for jobs for novelists, artists, journalists, musicians. From the earliest days, he poured money into the country for arts programs and cultural programs.”

So the Works Progress Administration opened about 100 arts centers throughout the country, including the only one in Washington: the Spokane Art Center, operating out of a storefront at 106 N. Monroe St.

The citizens of Spokane immediately embraced the idea and raised $4,000 in less than three months to supplement $12,000 in federal money.

The center opened in October 1938 and within a year had 27,000 dues-paying members, many of whom were taking classes in painting, drawing, printmaking and sculpting from the staff of professional artists.

And what a staff:

• Carl Morris, then 27, was teaching at Chicago’s Art Institute when he was hired as the first director of the Spokane Art Center.

He served as director for a little over a year before he was transferred to Seattle for another art project job. He later moved to Portland and became one of the most respected figures in Northwest abstract art.

• Hilda Grossman Deutsch was a New York sculptor hired to teach at the Spokane Art Center. She soon became Hilda Morris after marrying Carl Morris. She later became one of the Northwest’s most prominent sculptors, with many abstract bronze sculptures in public places.

• When Spokane’s own Z. Vanessa Helder was hired to teach painting, she had already been exhibited in New York. During her time at the center, the Seattle Art Museum gave her a one-woman show – a significant achievement for a woman artist of the time. She also became the only woman artist to gain access to the Grand Coulee Dam construction site.

In 1943, her work was included in a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Today, you’ll find her work at the Smithsonian, among many other museums.

• Guy Anderson was hired as an original faculty member. He is now known as one of the Big Four of Northwest art from the mid-20th century (the others being Mark Tobey, Morris Graves and Kenneth Callahan).

• Margaret Tomkins, who worked briefly as a faculty member, would go on to become one of Seattle’s most prominent artists.

Works by all of these artists are on display in the MAC exhibit. The centerpiece is Helder’s stunning 22-painting “suite” of Grand Coulee Dam paintings, displayed together for the first time in 60 years on one curving, flowing wall.

When Morris was first approached by the Federal Art Project, he had already lived in art centers like Vienna and Paris. When they asked him where he wanted to go, he said he’d like something in the West, near water.

“Have we got an ideal place for you,” the government agent reportedly replied. “They’ve got a waterfall right in the middle of the city.”

Morris and the other artists soon established a tight-knit creative community, occasionally scandalizing some of their more conventional Spokane neighbors. Apparently one teacher had to give up his figure drawing class when he dared to have his students draw from a nude model.

Yet mostly, residents were proud of the Spokane Art Center and flocked to it by the thousands for classes, lectures and exhibits. In 1941, the center hosted a traveling exhibit of 14 original Van Gogh paintings (along with 18 facsimiles), which attracted 3,700 viewers.

The center also turned Spokane, briefly, into a destination for artists from all over the Northwest. Some of the region’s most influential artists came to visit their friends on the faculty.

Sometimes, they stayed around long enough to produce new work. The MAC exhibit includes a painting by Morris Graves which he executed while visiting Spokane. It also includes paintings by Tobey and Callahan, who were friends with Morris, Anderson and many of the other faculty artists.

The Federal Art Project’s goal went beyond employment. The idea was to create an entire community of art lovers. Or, as the center’s original brochure said, to make art “a constant experience for the individual, beauty as a constant factor in his life.”

It succeeded in that as well. The MAC exhibit includes work by students such as Jane Baldwin, who went on to an important art career.

The Spokane Art Center also hosted the first-ever one-man show in 1939 by a local artist named Clyfford Still – who later became one of the founding fathers of abstract expressionism. (There are no Stills in the MAC exhibit, because the notoriously feisty artist left a will stipulating that his works can be shown only in a museum devoted exclusively to him.)

By 1942, World War II was raging, employment was up, and many New Deal programs were no longer necessary.

The Spokane Art Center closed down, never to return – except on the walls of the MAC, through April 10.