String leader

Acoustic guitar virtuoso Leo Kottke keeps on going on

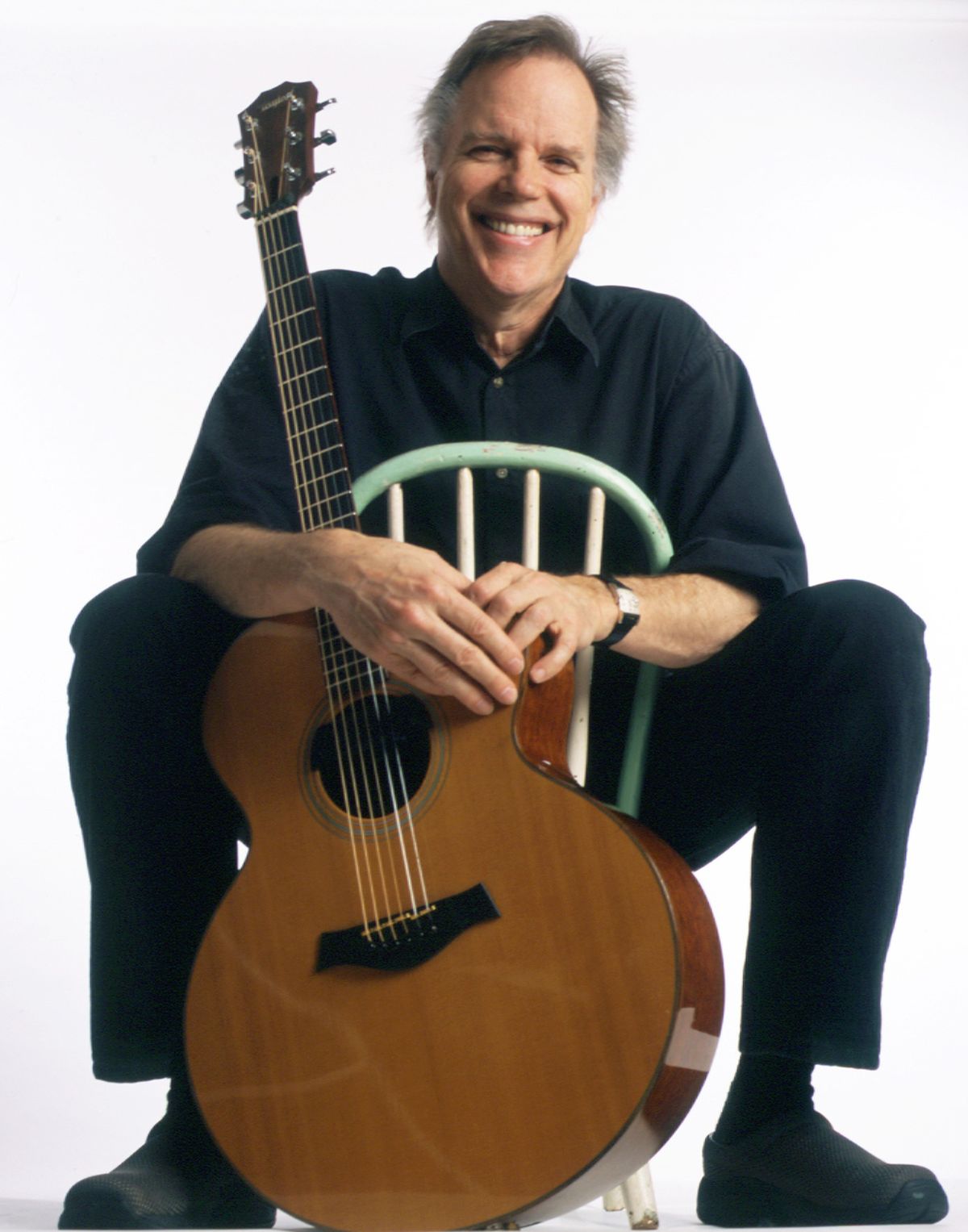

Leo Kottke relearned to play the guitar after suffering severe tendon damage.

As Leo Kottke told a group of college graduates in 2008, building up to what he acknowledged was starting to sound a lot like a commencement speech, the beauty is in the break.

“If failure were not a reality, there would be no space to jump into … where anything can happen,” the acoustic guitar virtuoso said at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “We learn to love the flaw, we cherish our losses as much as we celebrate our accomplishments.”

Kottke, who’ll play his six- and 12-strings this weekend in Sandpoint and Spokane, didn’t mention his partial hearing loss or the tendonitis in his right hand that threatened his career. Or the fact that as a child trombonist, he wasn’t fantastic, but managed to grow into a musician who’d make 30-plus albums; draw fans to concerts for 40-plus years; and receive two Grammy Award nominations.

He talked instead about Eddie James “Son” House, the Delta blues player, who’d suffered two heart attacks and a stroke a few months before a double bill with Kottke and could “barely reach” his guitar. House rose from his chair, Kottke told the graduates, and began to sing about a deep, dark night, “singing what no one wanted to say.” Kottke talked about country-music duo Homer and Jethro, who learned before a 1960-ish performance in North Carolina that no tickets had been sold – zero – and then played to an empty ballroom. And then played an encore.

He quoted from Samuel Beckett: “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

Kottke’s hearing loss resulted from a childhood firecracker mishap and then firing practice in the Navy. The tendon damage resulted from his use of fingerpicks.

He relearned to play, using his fingertips instead of picks, and has often said his sound was transformed for the better. Within reason, some aggravations are good for you, he wrote in an email interview this week during a break from the stage in Seattle, where he was scheduled to perform before heading east. He never considered another line of work.

“Except for the guitar,” Kottke wrote, “I am skill-free. (I wasn’t much of a trombonist.) … Getting rid of picks was the best thing I’ve ever done. And Charles Ives once answered a question this way, ‘What’s sound got to do with music?’ ”

First gaining attention with the 1969 release of his first album, “6- and 12-String Guitar,” Kottke builds on blues and folk to incorporate influences such as jazz and classical. Two of his most recent albums, “Clone” in 2002 and “Sixty Six Steps” in 2005, were collaborations with Phish bassist Mike Gordon.

In the email interview, Kottke also talked about performing live and playing with others.

Q. What can audiences expect from these concerts? Will you playing new music? Old favorites?

A. I never have a clue what I’m going to do. It’s better that way. A solo act with a set list is like an undertaker with a get-well card.

Q. People at your concerts seem to very much like your between-the-songs monologues. But you’ve suggested in previous interviews that you’re uncomfortable talking on stage. Is that true? Why do you do it?

A. I was unable to look up in performance for at least three years. One night, on stage with two goose-neck mic stands going all over hell and gone, I remembered trying to kill a chicken in Oklahoma with an albino E-flat clarinet player in about 1958. I was a trombone player at the time. The chicken won, I lost; after telling the crowd about this, and for the first time in my three-year career as a stiff, I knew what to play next. So I kept talking and, now, I look up sometimes.

Q. Are you singing on stage in this tour? You’re often called a guitar virtuoso, but you’ve compared your own voice to goose farts. Why add vocals?

A. Capitol Records made me sing. I’ve improved since then. So I do sing. Maybe 10 percent of the set. Some nights are better than others. The lyrics interest me more every year.

Q. Who or what inspired you as a musician at the start of your career? Who or what inspires you now?

A. The whole thing is the guitar. The sound, the geometry, the fickle, the arrogance. The guitar demands a lot for being nothing but a weird piece of wood. I threw one down a flight of stairs, smashed one against a pole, have kissed a few, and have been told that I play in my sleep. I’ll never stop.

Q. You’ve made reference to “stealing attitude” from other people. From whom, and why?

A. Because you can’t steal anything else. And because attitude will sneak in slowly and surface in you years later, when you say, “Son, what are you doing here?” I did a show with Son House when he was having a very rough night. But his performance was shattering. It was a pure gift. Dick Waterman was there and put the show together; he was Bonnie Raitt’s manager at the time. Son’s performance brought him, no hyperbole here, to his knees. And to tears. You never expect it, but sometimes you find out you’ve been wearing someone’s hat for a long time.

Q. Are you still playing with Mike Gordon? Do you have any collaborative efforts in the works? Who would you like to play with, and why?

A. There’s a good chance we’ll record again with Jon Fishman, the drummer. I hope we do it. But the other two records happened almost by chance. The first one was half done when we realized we had to get somebody to pay for it. So all we have right now is the intent. We’re likely to wind up in the same place at the same time and that’ll be it. I’d have to say it’s really the friendship. Fish I met before I knew who Phish was, and Mike, at a job in Vermont. If you need a good day, these are the guys.