‘Freedom Rider’ tells of ’60s push for civil rights in South

Max Pavesic wasn’t sure what awaited him as the train rolled into the station in Jackson, Mississippi.

During the summer of 1961, Pavesic was a 21-year-old college student and one of 436 “Freedom Riders” – activists committed to ending segregation on public transit in the South.

He was part of a group of 15 blacks and whites who had boarded the train together in New Orleans, in defiance of local segregation laws. They knew they’d be arrested in Jackson and possibly beaten. They expected an angry mob and police with dogs.

“We were considered outside agitators,” Pavesic recalled. “I don’t know if I was scared. It was more anticipation. You didn’t know what would happen.”

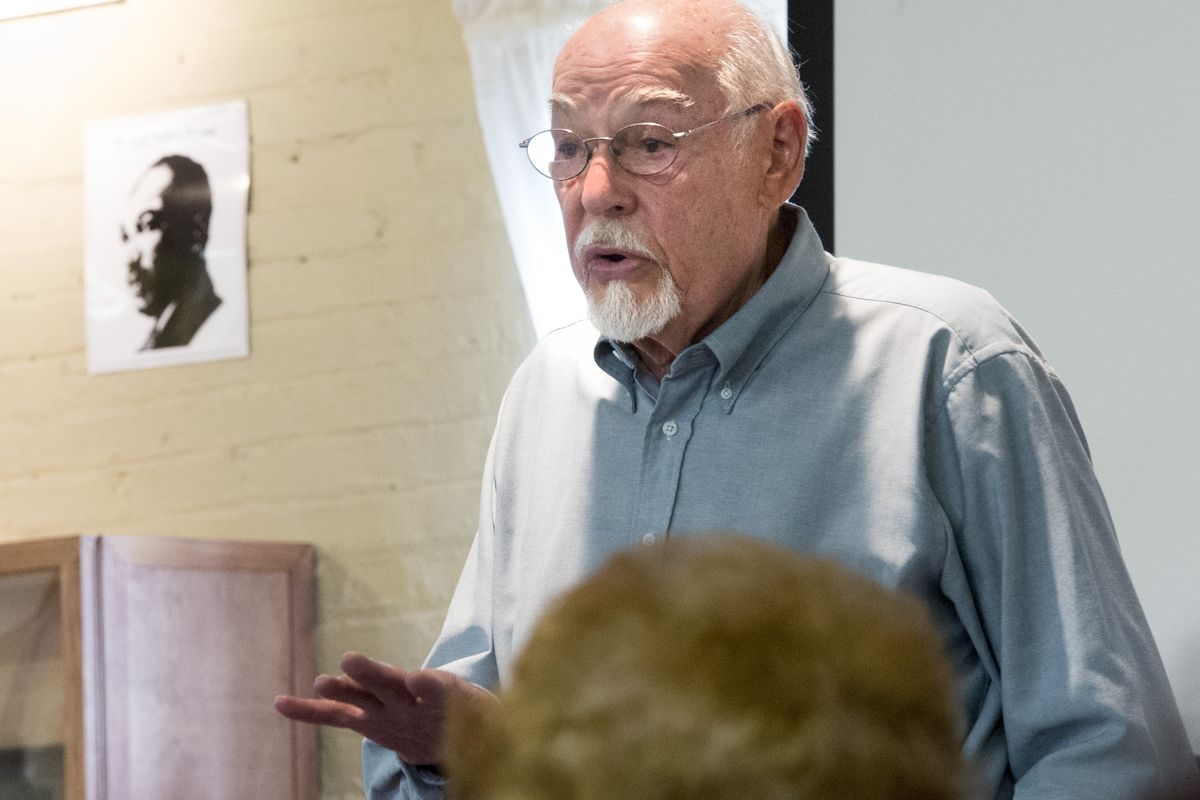

The retired Boise State University archaeology professor shared his story Friday afternoon during a talk at the Human Rights Education Institute in Coeur d’Alene. He encouraged audience members to continue to work for racial equality.

“Our society has to admit it is a racist society, and then we can start to change,” Pavesic, who now lives in Portland, told the crowd.

Pavesic joined the Freedom Riders at the urging of a classmate at the University of California-Los Angeles. The Congress of Racial Equality was organizing the rides that summer to challenge “Jim Crow” laws in the South, which included segregated public transportation. Bus and trains had “Whites Only” seating areas and waiting rooms.

The U.S. Supreme Court had struck down racial segregation on interstate trains and buses in 1946, but the ruling was largely ignored in the South.

Pavesic was already an activist, having taken part in protests against McCarthyism and compulsory ROTC training at state colleges. Stories about Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks moved him deeply. He abandoned plans to work on a New Mexico archaeology project and flew to New Orleans in late July.

Pavesic boarded the train with the others for the four-hour trip to Jackson. Six members of the group were black, nine were white. All but two were college students.

When they got off the train, Jackson’s chief of police arrested them in the “Whites Only” waiting room for disturbing the peace. Members of Mississippi’s National Guard were there with guns with bayonets. The Freedom Riders were whisked away in a paddy wagon, booked into the city jail and sent on to the state prison because the jail was full of other protesters.

His mug shot shows a young man with a flat-top haircut, in a crisp suit and tie. The National Congress of Racial Equality required the Freedom Riders to dress up, emphasizing that they were upstanding young men and women, not rabble rousers. But, “I think it was a matter of chance that we weren’t beaten,” Pavesic said.

Mississippi didn’t want the international publicity that had accompanied the earlier beatings of Freedom Riders in Alabama, where the Klu Klux Klan also firebombed a Greyhound bus.

Pavesic and the other Freedom Riders were held in the penitentiary’s maximum security block, isolated from other prisoners for their own safety. “Every night, we sang like meadowlarks to keep our spirits up,” Pavesic said. “We spent hours singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ and other freedom songs. It drove the jailers crazy.”

The Freedom Riders spent 30 days in prison before they were driven back to Jackson for their court hearing. When they started singing in the back of the truck, the driver pulled over and told them to shut up, or “we’re all going to get hurt.”

“He was ashen-faced,” Pavesic said. “He said, ‘I’ve been told where to drop you in the woods, and to leave you locked in the truck.’ Who knew what the Klan had in mind for us.”

Pavesic said that if he had known how repressive Mississippi was, he might not have joined the Freedom Riders.

“It was a violent time in a violent place,” he said. “The viciousness is hard to comprehend. … The powers that be were able to convince the poor whites that their problems were because of the blacks.”

Two years later, civil rights leader Medgar Evers would be gunned down in the driveway of his Jackson home.

Pavesic and the other Freedom Riders paid fines rather than serve out their six-month jail sentences. The Congress of Racial Equality provided most of the money for their travel, bail and fines. Folk singer Pete Seeger also gave two benefit concerts for them.

Their ride was the last one organized by the Congress of Racial Equality. In September 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered “Colored Only” and “Whites Only” signs to come down at bus and train stations.

Four years ago, Pavesic and other Freedom Riders reunited in Mississippi to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the rides. Both black and white residents thanked them for their activism. Their nonviolent protests helped build the credibility of the civil rights movement.

“We had an objective in mind, and we accomplished that,” Pavesic said. “I don’t know if anyone knew it was a tipping point.”