Gloria Steinem: A life on the road, but not behind the wheel

NEW YORK – Yes, she’s a driving force behind the women’s movement that transformed the lives of millions. But Gloria Steinem doesn’t, er, drive.

As in, doesn’t even have a license.

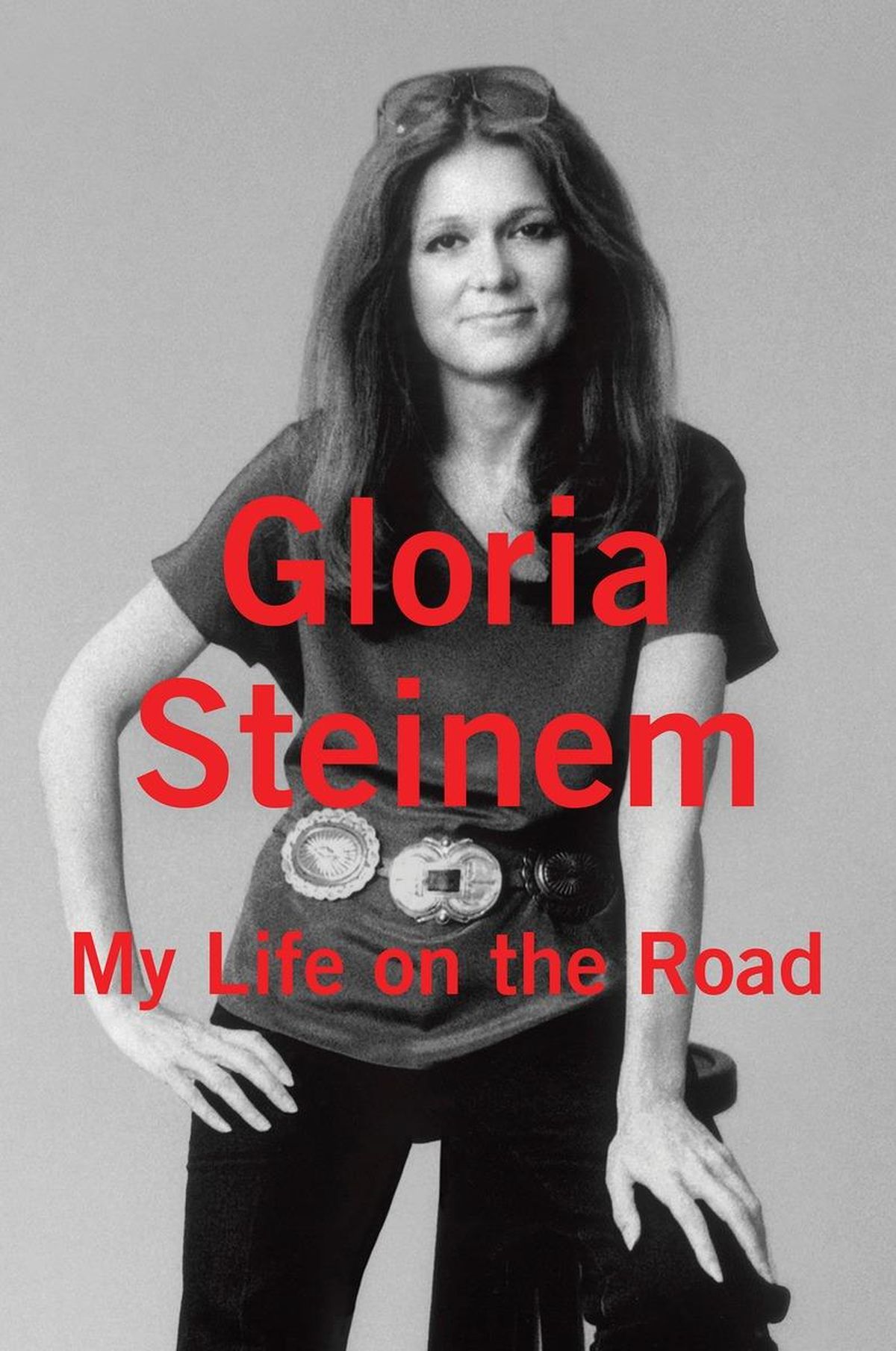

Steinem devotes a chapter to this interesting fact in her entertaining new memoir, “My Life on the Road,” a chronicle of her itinerant life. Though she has a wonderfully lived-in Manhattan home, chock-full of mementoes from a life of advocating and organizing around the country and across the globe, she spends only half her time there, at most. The rest is, well, on the road. But not behind the wheel. And there’s a reason.

“I would miss something if I drove,” Steinem says. It’s about communication. She loves talking to taxi drivers anywhere in the world, or arriving at a university for a speech and being driven by her hosts, who tell her what’s going on around campus. “That’s really crucial time,” she says. “I would not want to miss that.”

Steinem, now 81, has been working on her memoir for a good 20 years, on and off. Traveling wreaks havoc on one’s writing schedule, not to mention how it helps one procrastinate. And when we say travel, we mean to places like Botswana, where she spent her 80th birthday riding elephants. Or to North Korea, where, in May, she was part of a group of peace activists crossing the Demilitarized Zone by bus. In fact, Steinem says, she travels more now than ever before.

Which is why she decided to not write a traditional memoir, but a road book. “That word `memoir’ sounds pretentious, anyway,” Steinem says with a smile, settling into her living room sofa with her cat nestling contentedly in her lap for an interview this week. “Also, I’ve been writing books and articles and essays this whole time, but it somehow dawned on me that I was writing LEAST about what I was doing MOST. The fact that I was on the road more than half of my life was invisible.”

But it’s not just about recounting her own experiences; Steinem wants to encourage others – especially women – to head out, “because the road doesn’t belong to women, and it should. Women aren’t `supposed’ to go out on the road.” She also, incidentally, would like politicians to live up to their claims that they know the country. “They ought to be forced to go on the road for two years for every term they’re in office, because then they would stop saying `the American people’ as if there’s one,” she says. “Because it’s just so wildly diverse.”

There’s yet another reason for the on-the-road theme. Steinem fears that in our increasingly digital world, we may be forgetting the value of in-person communication. “Not to diminish the importance of the Web,” she says. “But it should be also obvious that people can’t empathize with each other unless we’re in the same room.”

And so Steinem’s anecdotes – and there are many – are often about chance encounters with people who made piercing observations, or lent unexpected support. She says she and her co-founders never would have started Ms. magazine, for example, if not for traveling the country. “Everybody in New York said starting a magazine like that was hopeless,” she says. Women across the United States convinced her that “the women’s movement wasn’t just 12 crazy ladies in New York and LA.”

It was also a woman in an audience who made Steinem laugh – then, and now – when discussing the constant problem of being judged by her looks. She points out in her book that she’d been called pretty before she became a feminist, and suddenly as a feminist she was called beautiful. The subtext, she says, was that feminists aren’t supposed to be attractive, and also that if she could get a man, why would she need equal pay? But an elderly woman stood up in an audience one day and told Steinem: “Don’t worry, honey. It’s important for somebody who could play the game – and win – to say, `The game isn’t worth (expletive).“’

Because of her status among women, Steinem is often asked where she stands politically – especially in election season. She supported Hillary Rodham Clinton for the Democratic nomination in 2008, a decision she says she made purely on the basis of Clinton’s experience in Washington versus that of Barack Obama, whom she wholeheartedly supported in the general election. In 2008, she didn’t think America was ready to elect a woman. Now, she says, “I think we’ve been able to see more women in authority in the public world. And part of that has been changed by Hillary herself as secretary of state.” Hopeful as she is, she warns it won’t easy: “The campaign is going to be hell.”

Steinem, who’s been a writer all her life, says the process was still difficult. “If you’re a writer and you really care about writing, you put it off,” she says. “You wax the floor.” Once she’d written her draft, she handed it to “two friends with machetes” who cut at least a third. Still, every day she thinks of a story she should have included. “I could follow each copy to the bookstore with a pencil in my hand,” she jokes.

There was, for example, the elderly Chinese man crossing the street who suddenly turned and asked what she thought of the late Margaret Thatcher. (Not much, she told him.) She was delighted by the exchange, which she sees as a reward of being open to new experiences – a way to be “on the road” without traveling.

Or her recent experience in a taxi. She saw a billboard with an image of Dracula, and remarked that she “didn’t understand this bloodsucking thing.”

And then the driver informed her that he was from Transylvania – and gave her an entire education in the origins of the Dracula tale.

You see? This is why Gloria Steinem doesn’t drive.

AP-WF-10-22-15 1914GMT