Review: Leonard Cohen and his muse are subjects of absorbing documentary

The absorbing documentary “Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love” chronicles the creative and romantic collaboration between musician Leonard Cohen and Marianne Ihlen, who inspired several of his earliest songs, including “So Long, Marianne.”

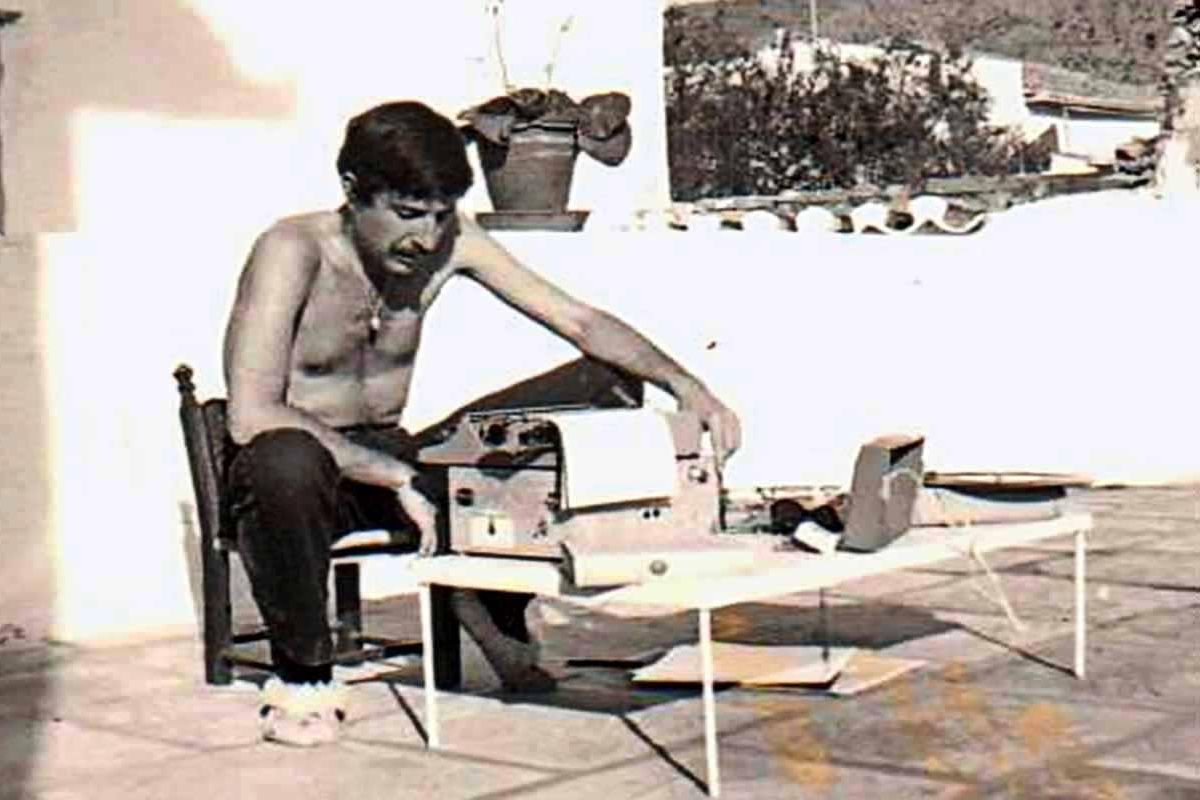

Cohen’s fans already know the outlines of their story: Having become a successful poet in his native Canada in the 1950s, Cohen decamped for the Greek island of Hydra, joining a group of expats, artists, drifters and bohemians attracted by the sea, retsina, free sex and LSD. It was there, in a market, where Cohen met Ihlen, the soon-to-be-single mother of a young son.

“There we were, two refugees,” she recalls in one of several audio recordings used in the film. The connection was instant and electrifying, and they would be a couple throughout the ’60s, during which time Cohen would transform from a relatively obscure poet to a folk star and, for depressive teenage girls of discerning taste, an unlikely sex symbol.

Those seismic personal and cultural changes are gracefully conveyed by filmmaker Nick Broomfield, who interleaves “Marianne & Leonard” with his own deeply intimate narrative: He met Ihlen in 1968 in Greece, and they maintained their friendship long after Cohen and she called it quits.

Filled with sun-kissed images of Hydra at its most hedonistic and idyllic, as well as mesmerizing footage from Cohen’s later tours, “Marianne & Leonard” includes several first-person accounts from the witnesses still around to tell the tale.

Broomfield does a particularly good job of immersing viewers in Hydra’s halcyon pleasures, then gently exposing the community’s darker shadows. Everything has its cost in this account, which is as valuable as social history as it is a compelling dual portrait of an artist and his muse.

There’s that word, which Ihlen carried – part honor, part burden – all the way to her death in 2016, just a few months before Cohen’s own passing. In “Marianne & Leonard,” the word “muse” is decidedly double-edged, meant to be praiseful, but always subtly patronizing.

Although it’s true that Ihlen nurtured and supported Cohen during the most pivotal chapter of his life, Broomfield reminds viewers that she had that effect on several of her friends, including folk singer Julie Felix. He also allows viewers to see her relationship with Cohen through a number of lenses, including a charmed love affair that became a doomed romance; the misreading of self-abnegation as feminine power; the alternately selfless and solipsistic quest of spiritual seekers; and the narcissistic pathologies of the masculine artistic ego.

It’s that insatiable force – and the fascinating ways it played out in Cohen’s personal and professional lives – that makes him the reflexive focus of “Marianne & Leonard,” despite the title’s suggestion of finally giving Ihlen her due. Dutifully covering the rise, fall and final triumph of Cohen’s career, Broomfield relegates Ihlen to the background of her own story before bringing her back for the film’s touching final act and devastating epilogue.

Achieving the kind of balance to which Cohen always aspired, “Marianne & Leonard” is heartbreaking and heartening in Zen-like equal measure.