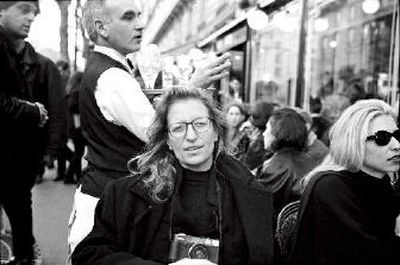

Image of photographer blurry

A picture says a thousand words; a studio photographer barely makes a sound.

For those driven to control their environment while avoiding the glare of the spotlight, there are few more enviable positions than the one behind the camera – making entertainers look like stars, and stars like icons.

No one in the rock era has been more successful from that vantage point than Annie Leibovitz, the photographer who is often more respected and more celebrated than her subjects.

Among her masterpieces: Bette Midler lounging in a bed of roses, Whoopi Goldberg emerging from a milk-filled bathtub and a naked John Lennon cuddling up to Yoko Ono – a shot taken just hours before his murder and one that Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner describes as “the Pieta of our times.”

They are all dissected, scrutinized and lauded in “Annie Leibovitz: Life Through a Lens,” airing tonight as part of public TV’s long-running “American Masters” series.

The ultimate mission for the documentary, directed by Leibovitz’s younger sister, Barbara, is to analyze the shooter herself. In that regard, the project is a bit of a blur.

Leibovitz, who at 57 still resembles a die-hard hippie, has conducted her business less like a free spirit and more like a secret agent, letting few fans see beyond the tripod. Even committed buffs were unaware of her long relationship with Susan Sontag until the writer’s death in December 2004.

In an interview, Leibovitz said it was Sontag’s passing, along with that of her father, that convinced her to share more with the public. That willingness coincides with her latest book, “A Photographer’s Life: 1990-2005” (Random House, 2006), which juxtaposes black-and-white family portraits with her more celebrated pieces.

“I just wanted to expose myself, just let it go,” she said.

If that was the goal, Leibovitz falls somewhat short onscreen, failing to provide much insight into her personal life. She alludes to years of drug abuse and then describes her rehabilitation only as taking a “deep, deep, deep breath and then moving on.”

She gets emotional when revisiting photos of Sontag but never fully explains their relationship. If you didn’t know better, you might think they were just fishing buddies.

Commentary from other guests – an impressive list, from Hillary Clinton to Mick Jagger – is much sharper.

Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter labels her as “Barbra Streisand with a camera.” Gloria Steinem calls her “the tallest and most authoritative, uncertain person I’ve ever seen.”

Those quotes may not express a thousand words, but they say a heck of a lot more than the subject herself.

Leibovitz does manage to share thoughts on her methodology, if only because it’s so stunningly simple. Her ideas are often blatantly obvious – putting Chris Rock in whiteface, having Demi Moore rub her naked, pregnant belly – but they stay with you long after the magazine gets tossed in the recycling bin.

Appreciating them on the small screen is another matter. Photography, like all visual art, is best appreciated when there’s time to stare, linger and stare again.

In this fast-moving film, you’re lucky to get four seconds.

No amount of time, however, gets us much closer to Leibovitz. By the end, she’s a master subject but one that remains out of focus.