PRIVACY put on hold

Spokane resident Carol Mathison was shopping at The Buckle, a clothing store at the Spokane Valley Mall recently. She handed the clerk her ATM card to buy two shirts, and the clerk asked for her address and her phone number.

Why? The clerk explained that was the store’s policy. It was helpful in dealing with refunds or exchanges, Mathison said she was told by the clerk and by the store manager.

Deciding that information was unnecessary, Mathison walked out without making the purchase.

Consumers across the country are raising similar questions over privacy, worried that too much information is being captured and, possibly, misused.

At the same time, merchants say they’re battling a flood of fraud, identity theft and abuse of retail product-exchange policies. They say they need that personal information from consumers to ensure they know who they’re dealing with, and that gathering information also deters customer from fraud or theft.

Laws covering the capture of personal consumer information in the United States are vastly different from similar laws in Europe. In essence, European countries would have prevented stores like The Buckle to ask that information of shoppers like Mathison. Only information deemed relevant to the sale is allowed, said Jane Winn, a University of Washington law professor and author of the book “The Law of Electronic Commerce.”

But in the United States, if a law doesn’t forbid asking for specific personal information, merchants are free to ask for it — and anything else — as part of the transaction, said Winn.

Even one’s Social Security number — the primary identifier used by nearly all agencies and medical providers — can be requested by a business. Very few companies ask for it, with the exception of banks or financial institutions that need that number and must provide it to the Internal Revenue Service to create a customer account.

At the same time, customers are free to vote with their feet and refuse to do business with businesses seeking personal information such as a copy of a driver’s license or a home phone number, said Paula Selis, a senior counsel with the Washington state Attorney General’s Office.

“It’s clear there are competing issues here, with consumers wanting to protect privacy and the business world knowing that the more information they can collect, the more they can target customers,” said Selis.

Laws in Idaho are similar to those in Washington, allowing a merchant wide latitude to ask for driver’s license numbers, phone numbers, home addresses, even an e-mail address, as part of a transaction, said state officials.

Winn said businesses like The Buckle gather information partly to offset problems being created in the retail industry, including fraud and rampant misuse of refund policies.

“In part we’re seeing changes in what has been a period in this country of the most generous product exchange policies of all time,” she added. “The problem with generous exchange policies is you get targeted for fraud.”

Companies like Target, Costco and Nordstrom, known nationwide for their simple exchange policies, have begun shifting and modifying those provisions because thieves, frauds and “chronic returners” have learned to game the system, she said.

The National Retail Federation estimates refund fraud bilked American retailers out of $9.6 billion in 2006. Returning stolen items is the No. 1 offense, followed by counterfeit receipts and returns of items bought at a different store.

The federation said 69 percent of retailers modified their return policies in response to fraud. Changes include shorter time limits, restocking fees and requirements for original packaging.

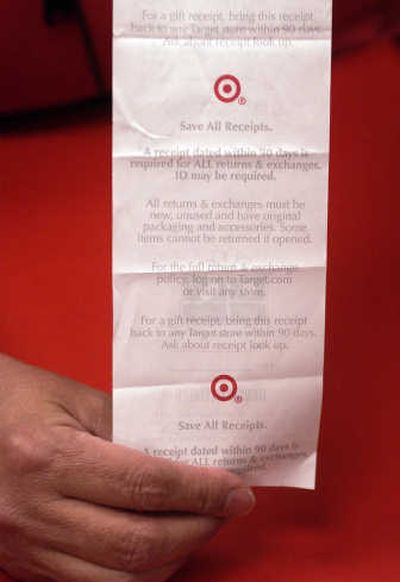

Target Stores, for example, changed its store refund policy that formerly allowed a full $100 refund to a customer who returned an item without a receipt.

In August, that policy changed; now customers can only return items priced at $20 and less without a receipt to get a refund, said spokesman Joshua Thomas. Purchases made by credit card always generate full refunds, Thomas noted.

Costco also changed its policies for refunds. Consumer electronic products that customers could have returned at any point after purchase now must be returned for refund within 90 days. That applies to all items except computers, said Richard Galanti, the company’s chief financial officer.

Winn said research has found that there’s a “90-10” problem faced by large- and medium-sized retailers. That says that roughly 90 percent of all consumer problems a company faces come from about 10 percent of their customers.

Much of that problem is due to the practice of chronic returns — estimated to affect 56 percent of retailers, according to the NRF. Also called “wardrobing,” Winn said that’s the practice of returning non-defective, used merchandise.

That practice especially hurts smaller companies, said Winn. If a customer buys $400 of clothing with a credit card, the merchant typically pays a 3 percent fee to the bank handling the credit transaction. If that customer comes back and seeks a refund, the chargeback — the transfer of cash back to the consumer’s credit account — might mean another fee imposed on the merchant, she said.

“That’s not shoplifting,” said Winn, “but it takes advantage of a store’s generous return policy and causes problems.”

So Winn said it’s possible The Buckle’s policy is part of an effort to stay profitable by creating “hoops” to discourage abuse by users of exchange or refund policies. “Some companies may even be creating profiles so their employees in stores can identify the worst offenders,” said Winn.

Kyle Hanson, corporate counsel for Kearney, Neb.-based Buckle Inc., which is publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange, declined to explain how and why the company collects personal consumer information.

Holly Towle, a Seattle attorney with the firm K&L Gates LLP, said it’s unlikely state or the federal lawmakers will change the current status and try to regulate what consumer information can or cannot be required by businesses.

Business interests have traditionally opposed such restrictions, she said. In 1999, former Washington Attorney General Chris Gregoire proposed a bill that would have banned businesses from collecting some information. That bill never came out of the Legislature due to widespread business opposition.

Towle, who works on the areas of electronic commerce and intellectual property, contends consumers are better off if the government doesn’t specify which parts of personal information are to be totally guarded.

“When you codify that question, when you define what it is that shouldn’t be handed over, you effectively tell identity thieves what their target should be,” she said. “That’s how the Social Security number became the big target for identity thieves. We made it the No. 1 piece of personal information. We shouldn’t do that with other information either.”