‘Stop-Loss’ through eyes of enlistees

There wasn’t much on Kimberly Peirce’s resume to suggest she would be the ideal filmmaker to take a shot at making an Iraq War drama.

But something about 9-11 moved the director of “Boys Don’t Cry” (1999) to postpone her years-long struggle to make a film about an infamous Hollywood murder and take on the war and its impact on the home front, on her “people” – among them, her younger brother.

“It felt personal, this war,” says Peirce, 40. “I saw this seismic change in the culture, young people signing up for the military.

“My younger brother signed up. It really hit home then. I wondered what they were going through in combat and what it was like for them coming home.”

“Stop-Loss,” which opens in theaters Friday, is the movie that came from her wondering.

A film that takes us from house-to-house, room-to-room combat in Tikrit to a rural Texas homecoming and its aftermath, it has Peirce’s “Boys Don’t Cry” grasp of rural culture and mores.

And it has bang-up combat sequences, “an impressively staged and powerfully kinetic battle in Tikrit,” says Variety critic Joe Leydon.

“I did a huge amount of studying how I wanted the combat to look,” Peirce says.

“I’m a big fan of war films and went back through all these great World War I, World War II films, onward – ‘All Quiet on the Western Front,’ ‘Best Years of Our Lives,’ ‘Apocalypse Now,’ ‘Coming Home,’ ‘The Deer Hunter,’ ‘Patton.’ I love these movies.”

Pierce says she wanted to make a comment on how the most patriotic among us, those who enlisted, are being penalized for that patriotism by the military’s “stop-loss” program – in which their tours of duty are involuntarily extended.

“It’s a weird word,” she says. “The soldiers are stop-lossed, at least 81,000. The families are stop-lossed. And in a way America is stop-lossed, because you’re just recycling those resources that need to be utilized in a better way, and clearly we need to figure out some solution.”

Most importantly, Pierce wanted the chance to show her respect for a part of the culture often mocked in the media and in film: small-town Southern patriotism and gun culture.

“The more I talked to soldiers, the more I realized I had to find a way to dramatize that culture,” she says. “And while city kids are patriotic and have signed up, there’s something different about the South. …

“I like stories about the heartland, and in this case, Texas, where the value system feels more real and authentic, somehow. I wanted to capture that and give it the dignity it deserves.

“That small-town rural life of guys drinking, target shooting, that’s kind of the world I grew up in. Boys will be boys, especially in the country. I always related to that. They’re like my family.”

The reviews aren’t all raves, and “Stop-Loss” will be facing the long box-office odds that every other Iraq War/War on Terror film – from “In the Valley of Elah” to “Rendition” to “Lions for Lambs” – has faced.

Peirce is braced for that.

“I think this is a totally different movie from those other movies about Iraq,” she says. “It’s from the soldiers’ point of view. And while we spend time with these characters in combat, it’s really a story about relationships between the men and their families when they return.

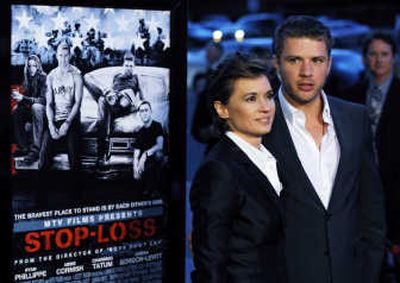

“And this movie is geared toward a younger audience, because that’s who’s fighting the war. We didn’t cast movie stars. We cast boys, young actors (Ryan Phillippe, Channing Tatum, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt) who aren’t stars but who are the right age. This movie is more inside that culture.

“I guess what I’m hoping is that if you’ve got a good story and a good bunch of boys, people will come see it.”