Deceptive by design

Woodcarver brings duck decoys out of the water, onto museum walls

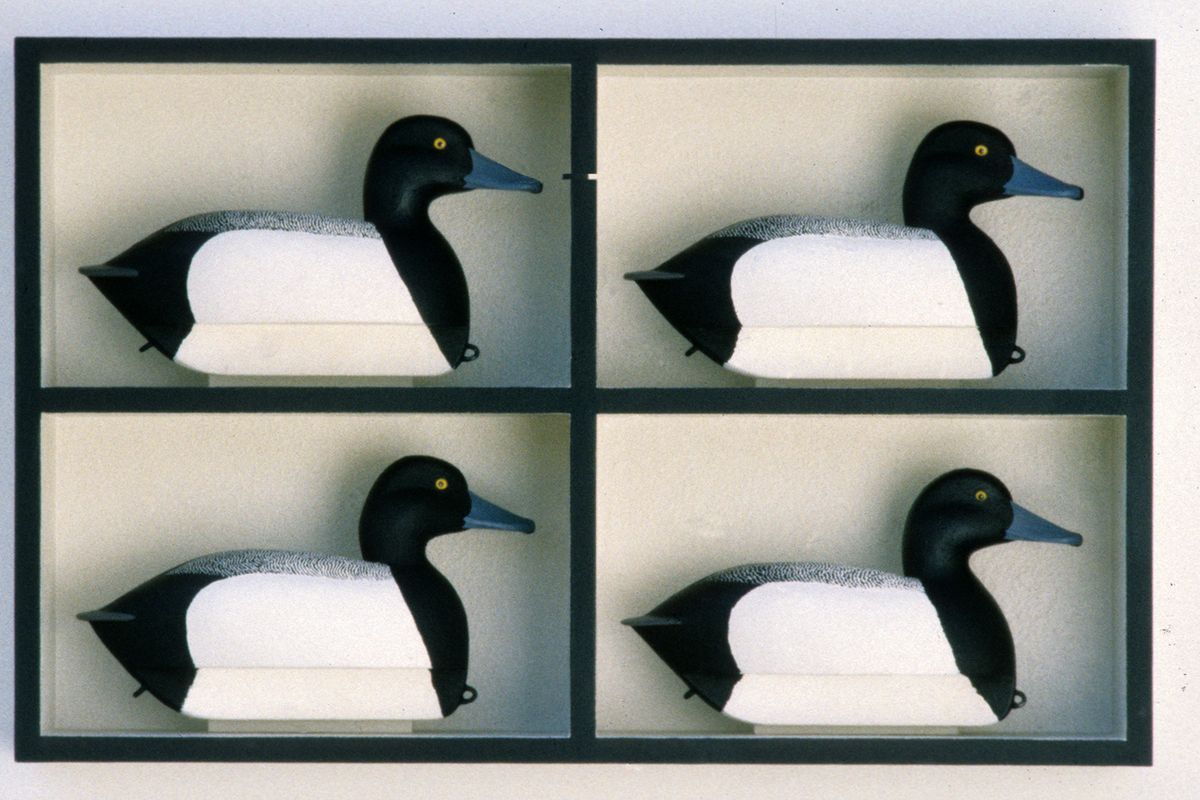

He put his birds in boxes and hung the boxes on the wall as an announcement, or an insistence, to the world: These fake ducks are art, too.

He was trying to address some problems.

Frank Werner, a hunter and decoy carver who deploys his birds on the south end of Lake Coeur d’Alene and in art galleries, called them “the historical problems” – inequity in recognition and funding for the folk arts compared with the fine ones.

“I think the traditional arts is a very important part of the American visual scene, and it does not get its fair shake in the institutions,” said Werner, of St. Maries.

Werner seemed to be doing OK last week, though, talking about his work in an interview before he was to give a lecture at the Jundt Art Museum at Gonzaga University. His decoys are on display at the Jundt in an exhibit called “An Art of Deception,” part of the “Close-In” series highlighting regional artists.

Werner’s show provides a catalyst for good questions about what belongs in an art museum, said Karen Kaiser, the Jundt’s curator of education.

People who visit the museum come with “a strange idea” about what counts as art, she said.

“Once the work comes into the museum, then its character changes, and in lots of ways it sort of validates the work in a different way,” Kaiser said.

The value of Werner’s decoys – their beauty and functionality – is apparent, she said, as are his artistic influences. His installation is more formal than most that have appeared at the museum.

Glass pieces by Dale Chihuly flank the lounge where Werner answered questions before his lecture, and Chihuly’s 1,500-pound “Gonzaga Red Chandelier” hangs overhead, glass tentacles twisted.

Visible from the lounge through floor-to-ceiling windows, 50 Canada geese, real ones, bent their necks to the grass outside.

Werner’s decoys hung in glass-fronted cases nearby in the Arcade Gallery, just outside the museum’s main gallery, which was lined with photographs by Andy Warhol.

Werner said he would talk in the lecture about his process – audiences consistently want to know how he makes the decoys. He starts in the woods, he said, cutting, milling and drying trees he buys from the U.S. Forest Service.

But then he’d move to the historical problems. That’s where the boxes come in.

Werner has been carving and painting decoys since 1974. He creates a gamut of them, ducks and geese and swans, from very plain to highly detailed.

To show them as art, he installs the decoys in wooden grids, one bird in each rectangle. He puts them together as pairs and trios and sextets. He has one nine-bird assembly at the Jundt, about as many as he can hang on the wall as a unit.

He said he drew inspiration from the work of Joseph Cornell, an American artist who helped pioneer assemblage as an artistic process. Cornell also put birds in boxes, mounting their images on wood and installing them against white backdrops.

Werner started by putting two birds in one box – carved and painted doves – and putting the box on a wall. Putting something on the wall in an art space is a declaration of art, plain and simple, he said. It’s a demand to the viewer: Look at this art.

“And lo and behold it got into a juried show in Denver,” he said. “I was more surprised than anything.”

Then he turned from the box to the grid, which as a visual form has been so reliably employed by contemporary artists that it announces the “modernity of modern art,” art historian Rosalind Krauss wrote in her 1979 essay “Grids.”

The gridded box offered Werner a way to amplify his announcement – his declaration of art – and to move his decoys from the “arts ghetto”: the bookseller’s window, the wall behind the teller’s counter at a bank, the Boise airport.

But it also offered the artist a better way to display his work in context, which, in the case of duck decoys, means in groups. Duck hunters deploy their decoys in rigs on the water, connected by lines and anchored by weights. A solo decoy is useless as a functional object. And Werner insists that his decoys, however nice to look at, are utilitarian first.

Grids have multiple little boxes, uniting multiple decoys.

Werner started getting into more art shows. In other words, he said: “People in the art world started to understand.”

Werner’s decoys have appeared in dozens of shows at arts centers and museums and art galleries. He is a past recipient of the Idaho Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts and several fellowships from the Idaho Commission on the Arts.

If the problem was a lack of recognition, he may have solved it, as least for himself, although he said he’s interested in the problem as it faces other traditional artists, too.

But here’s the thing, Werner said. Ducks in boxes on walls don’t pan out as he imagined they might.

“I thought when I first started this I could form some synthesis between contemporary and traditional,” he said. “I thought it’d be a great idea – not a bridging-a-gap, but a fusion. It does not work.”

That’s because, aside from being put in little jail cells, he said, his birds “retain their cultural independence.” A duck decoy in a box on a wall is still a duck decoy, a tool employed by hunters and belonging to their community, rather than the broader popular culture.

Werner is OK with that. In fact, he likes it.

“What’s coming out of this is a real tension,” he said, between the folk art and the sterile, minimalist gridwork structure. “I enjoy that.”

His waterfowling friends, not so much. They don’t come to his shows.

“The duck hunters prefer seeing the birds in the water,” he said. “That’s a fact.”