‘Educated’ author Westover talks in Spokane about her survivalist childhood, meaning of learning

In her quest for a formal education, Tara Westover taught herself algebra. It helped the daughter of survivalist parents, who’d never attended school, gain admission to Brigham Young University, and eventually Harvard and Cambridge.

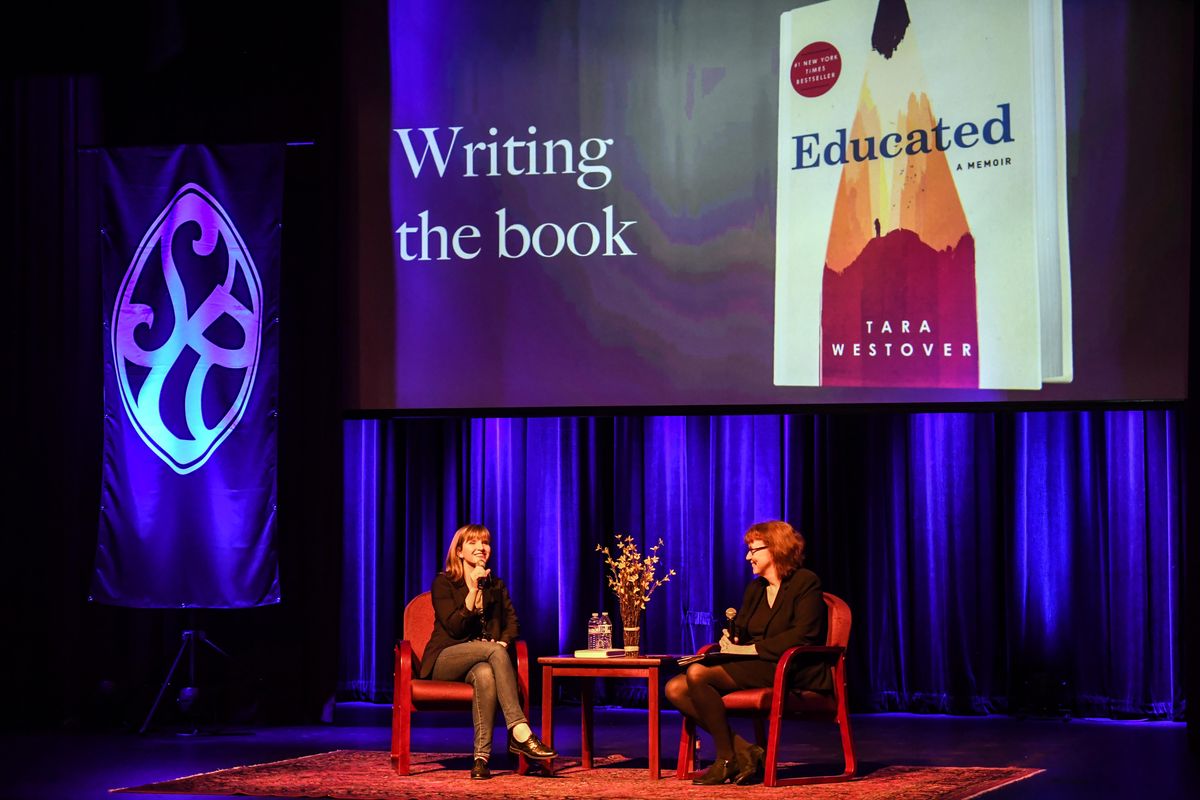

But an education isn’t all about book learning, the best-selling author told a crowd of about 700 at the Bing Crosby Theater on Thursday night.

“What an education is is the individual’s pursuit of understanding,” Westover said. “I think an education is about making a person, not making a living. That’s a side effect.”

Westover’s best-selling book, “Educated,” which describes her childhood growing up in a family in southeastern Idaho, dominated by a fearful, authoritarian father.

Her father was a junkyard owner, who believed that armed government agents would someday surround the family’s mountain property in a Ruby Ridge-style standoff. Her mother was an unlicensed midwife and herbalist.

There was no formal schooling for Westover, the youngest of seven children, no modern medical treatment and, for many years, not even a birth certificate. But there was a survival pack, intended to help her survival an Armageddon.

Westover’s memoir describes how she broke away from her close-knit, but troubled family, to attend Brigham Young University as a 17-year-old, and eventually earn a Ph.D. in history at Cambridge. It was a difficult journey for a girl who was told that learning to read was good enough.

Westover’s Spokane appearance was hosted by Northwest Passages Book Club, which is a program of The Spokesman-Review. The monthly forums feature literature of the West, including works by Spokane-area authors and nationally acclaimed writers.

Westover’s memoir is “a beautifully written and poignant coming of age story set right here in our region,” said Donna Wares, the newspaper’s senior editor for community engagement. “It’s the story of someone who wasn’t given an education and sought it out on her own.”

Gonzaga University President Thayne McCulloh read the book’s opening prologue, which described the mountain where Westover grew up, and the school bus that rumbled by every morning without stopping. It was one of the things that defined her family, Westover said: They didn’t go to school.

Much of the book talks about Westover’s pursuit of formal education. But being in a classroom by itself isn’t an education, she told the near-capacity crowd.

She credited “the people I met, the conversations I had, the books I read, and sometimes the classrooms” for her education.

Terri Barros, a human resources director from Spokane, asked Westover what she would do if President Donald Trump appointed her to replace U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. Westover said students should have more choice on what they want to learn and what passions to pursue.

Despite her difficult childhood, her parents helped shape her education, Westover said. “They had this idea you could teach yourself things – maybe even better than someone else could teach you,” she said. “There is no substitute for wanting to learn.”

Westover’s words resonated with Lucy Clifford, a fourth-grade teacher at the Ramsey Magnet School of Science in Coeur d’Alene.

“I was overwhelmed by Tara’s story of hiding and crouching behind the sofa to read the encyclopedia and teaching herself,” Clifford said. “How do you cultivate that feeling in a child of, ‘I want to learn’?”

Leigh Hancock, a sixth-grade teacher at Lincoln Heights Elementary School, said she sometimes forgets to appreciate how every child’s experience is unique.

“We have kind of gotten away from what an individual brings,” she said. “Everybody can get a diploma, but what (Tara) went through, no piece of paper is ever going to show that.”

Westover also talked about religion, her estrangement from her family, and her motivation to write the book.

Though her family was Mormon, it wasn’t the cause of her family’s dysfunction, she said.

“My dad was extreme in his life. … I feel he was bipolar,” she said. The extremeness “manifested itself through religion. I never felt it was Mormonism or the church.”

She eventually broke ties with her parents and some of her siblings. Few people talk about those kind of ruptures in relationships, she said. It made her experience more isolating.

“Now I know that a lot of people experience it,” she said. By writing about her difficult break with her family, Westover said she hopes that others with similar experiences won’t feel so alone.

Even after she recognized her family’s dysfunction, Westover kept going back for visits.

Difficult relationships are not all one thing, Westover said. “It’s hard to walk away from the good.”

“There was a lot of beauty in my childhood,” she said. “It took me a long time to realize it wasn’t completely normal.”

Reporter Will Campbell contributed to this report.