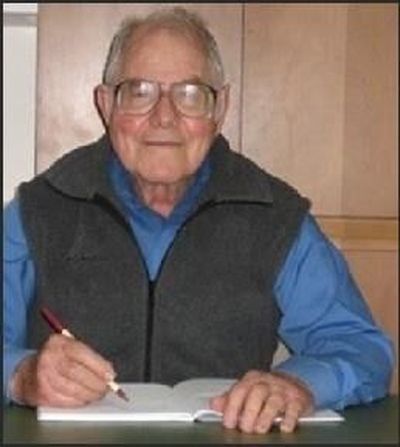

‘He really was the conscience of the place’: Longtime Gonzaga professor who left German army after being drafted in WWII dies at 93

In 1944, toward the end of World War II, the Nazi army drafted 15-year-old Franz Schneider.

“The German army was drafting any male that was capable of moving,” said Mike Herzog, a friend of Schneider’s.

Just 13 years after manning anti-aircraft guns as a teenager, Schneider was an English professor at Gonzaga University. He held that position for more than three decades, retiring in 1993. He died April 14 at 93.

Born in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1928, Schneider was the middle child in a Catholic family with five sons. The Schneiders were part of the Nazi resistance movement.

“His upbringing was totally against everything the Nazis stood for,” said Herzog, who taught medieval literature for 45 years at Gonzaga. “So to be put in that position was pretty horrific.”

Herzog said Schneider’s brief time in the German army influenced him for the rest of his life.

“I think it had a lot to do about his willingness to speak up or speak out when he saw injustices,” Herzog said. “He really was unafraid, and maybe that’s what happens when you’re (15) years old shooting anti-aircraft guns with bombers overhead shooting at you.”

Schneider went AWOL in 1945. He went on to study English and German literature at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, then came to Washington State University in 1948 as an exchange student.

He met his future wife, Ann McCrea of Aberdeen, Washington, at Washington State . The couple went on to have six children, who grew up in Spokane.

Schneider received a master’s and doctorate from the University of Washington. In 1957, he joined the Gonzaga University English Department as a comparative literature professor, with a special love for epic poetry. He often gave talks and spoke about his experience living under the Nazi regime.

“At times the only promise for liberty rests with those who can oppose corrupt political power with military might,” Schneider said at a 1958 talk reported in the Spokane Daily Chronicle.

At various times he chaired the Gonzaga English department and was the director of the school’s honors program. Schneider was a prominent figure on campus, Herzog said.

“Everybody knew Franz Schneider,” he said. “For a large part of his time at Gonzaga, he really was the conscience of the place. He always fought for what was right and tried to speak up against what was wrong, and was fearless.”

Herzog wasn’t just Schneider’s colleague and friend for decades, he was also one of Schneider’s pupils as an undergraduate student at Gonzaga.

Schneider loved the epics, including Dante ’s “The Divine Comedy,” and modern poetry – William Butler Yeats, T.S. Eliot, James Wright, Rainier Maria Rilke and Gerard Manly Hopkins were some of his favorites. Schneider also translated books, including “Last Letters from Stalingrad,” a collection of letters written by German soldiers during World War II.

He was an inspiring teacher, Herzog said, explaining that it was Schneider who guided him toward graduate school.

“It was amazing the kind of impact he had,” Herzog said. “He was the kind of teacher that was not afraid to call you out and say, ‘Hey, I know you can do this better.’”

Herzog noted that when he returned to Gonzaga as a professor, Schneider always treated him as a peer.

“If I had to describe Franz in one word … he was a mensch,” Herzog said. “It means human being in the fullest sense of the word. For me, that sums up Franz.”

Friends and family are invited to a funeral Mass at 11 a.m. Saturday at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, 501 NW 25th St, in Corvallis, Oregon. Contributions in Franz’s memory may be made to the educational nonprofit Indigenous Peoples Institute.

You also can share your thoughts and memories of Franz at www.demossdurdan.com.