Masae ‘Patti’ Warashina, 82, is ‘the Queen of Northwest Ceramics’

As a teen growing up in Spokane, Masae “Patti” Warashina was focused on getting her education and getting out of town. She never dreamed of gaining international fame as “the Queen of Northwest Ceramics.”

Nor did Warashina, 82, ever imagine that more than 60 years after leaving Spokane, the Smithsonian would honor her with the 2020 Visionary Artist Award for “rising to the pinnacle of sculptural art and design.”

It has been almost two decades since Warashina has held a show in her own hometown. Mostly because “nearly everyone I used to know in Spokane has died,” she noted, laughing.

Despite the lack of familiar faces, the groundbreaking ceramicist, whose work is featured in the permanent collections of museums worldwide, will return to her birthplace this First Friday with a solo exhibit at Marmot Art Space in Kendall Yards. The white box gallery will host a small retrospective of Warashina’s works, and the artist plans to be there 5-8 p.m. to greet patrons.

Warashina doesn’t intend to visit her childhood home while in Spokane. “My brother said don’t go by our old house. It’s a disappointment,” Warashina said. “They didn’t take care of the yard.” Warashina’s mother inspired the young Patti with her resourcefulness and artistry around the house, especially when it came to their oversized property near Franklin Park.

Although her mother was raised and educated in Tacoma, she employed Japanese methods of tying down branches and shrubs to transform their vast garden into an astonishing array of topiary. “The yard really was fantastic,” Warashina said with a sigh.

Perhaps even more amazing than her mother’s creativity was her resilience. During World War II, when Warashina was still a young child, her entire family had been traumatized when her father, a local Spokane dentist and community leader, was investigated by the FBI, their bank account frozen, and their home searched for subversive materials.

All U.S. citizens of Japanese descent lived under the threat of incarceration in concentration camps by their own government during World War II. “There was a lot of suspicion,” Warashina said.

Further heartbreak came when Warashina’s father died of stomach cancer when she was just 11 years old. She watched her mother take jobs to support the family, modeling the strong work ethic and fierce independence that Warashina would embrace in her own life.

It was science, not art, that became Warashina’s focus during her high school years at Lewis and Clark, and her sights were set on the University of Washington in Seattle. Already veering into untraditional territory for a female in the 1950s, Warashina’s Japanese heritage meant that she had other obstacles to face.

“It was definitely a predominantly white culture in Spokane,” she said. “One of the reasons I went to Lewis and Clark was because there was a larger community of Japanese there in that central area than in my neighborhood school (of Rogers High).”

With her trademark ambition and forward movement in all things, Warashina said she “got what I needed” out of high school and promptly moved to Seattle, where the ocean and vegetation enthralled her.

She was required to take electives at UW and chose to enroll in a drawing course even though she “didn’t know what a charcoal stick was.” After peeking through an open door of a ceramics studio one day, Warashina caught her first glimpse of the rest of her life.

“Once I hit that class, it was over,” Warashina said. “There was something about the material that I really liked. It changed my life.” Warashina threw herself into the studio like clay on a potter’s wheel, soaking in the teachings of some of the most influential figures of Northwest ceramics and sculpture. She soon became a trailblazer in her own right.

Before she had even graduated with a master’s in 1964, she held her debut exhibition with her first husband, fellow grad student ceramicist Fred Bauer, at the Northwest Craft Center at the Seattle Center.

The Seattle Times art critic (and later bestselling novelist) Tom Robbins called them “the two outstanding young potters in the region” and described Warashina’s pots as “shimmering with glazes that often seem ephemeral clouds of evaporating color.”

Her art continued to evolve over the years, from stoneware vessels and functional pots to humorous vignettes and figures. In 1965, she was included in the 10th International Invitational Ceramic Exhibition at the Smithsonian and the Craftsmen USA ’66 exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York.

Her sculptures in the late 1960s of huge lips propelled her into the burgeoning pop art movement. Her colorful sculptures “Ketchup Kiss” and “Unchilled Lips” were as trippy as rock and roll posters.

“I wasn’t trained in school in the human figure at all because it wasn’t fashionable. Back then, everything was about abstract expressionism,” Warashina said. “But I started using parts of the figure to model, like I’d do a giant lip.”

Abstract expressionism might have been all the rage, but Warashina’s flirtation with the human figure continued to grow. “The abstract expressionist movement typically meant using large brush strokes or kind of attacking the material, in this whole forceful, brutal movement, very gestural,” Warashina explained. “All my clay work just started to get tighter (instead).”

“So, getting into figures was very slow … and I had to work myself into it,” Warashina said. “I finally worked myself into making cars, which gave me a lot of confidence to do the full figure.”

Warashina became a leading artist in the West Coast Funk Art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and fellow ceramicists took notice. In 1970, legendary artist Robert Sperry hired Warashina to come back and teach at UW, and in 1976 they married.

She taught at her alma mater for 25 years until she retired to take care of Sperry, who died of bone cancer in 1998. Both ceramicists brought fame and influence to the university’s ceramics department with their innovations.

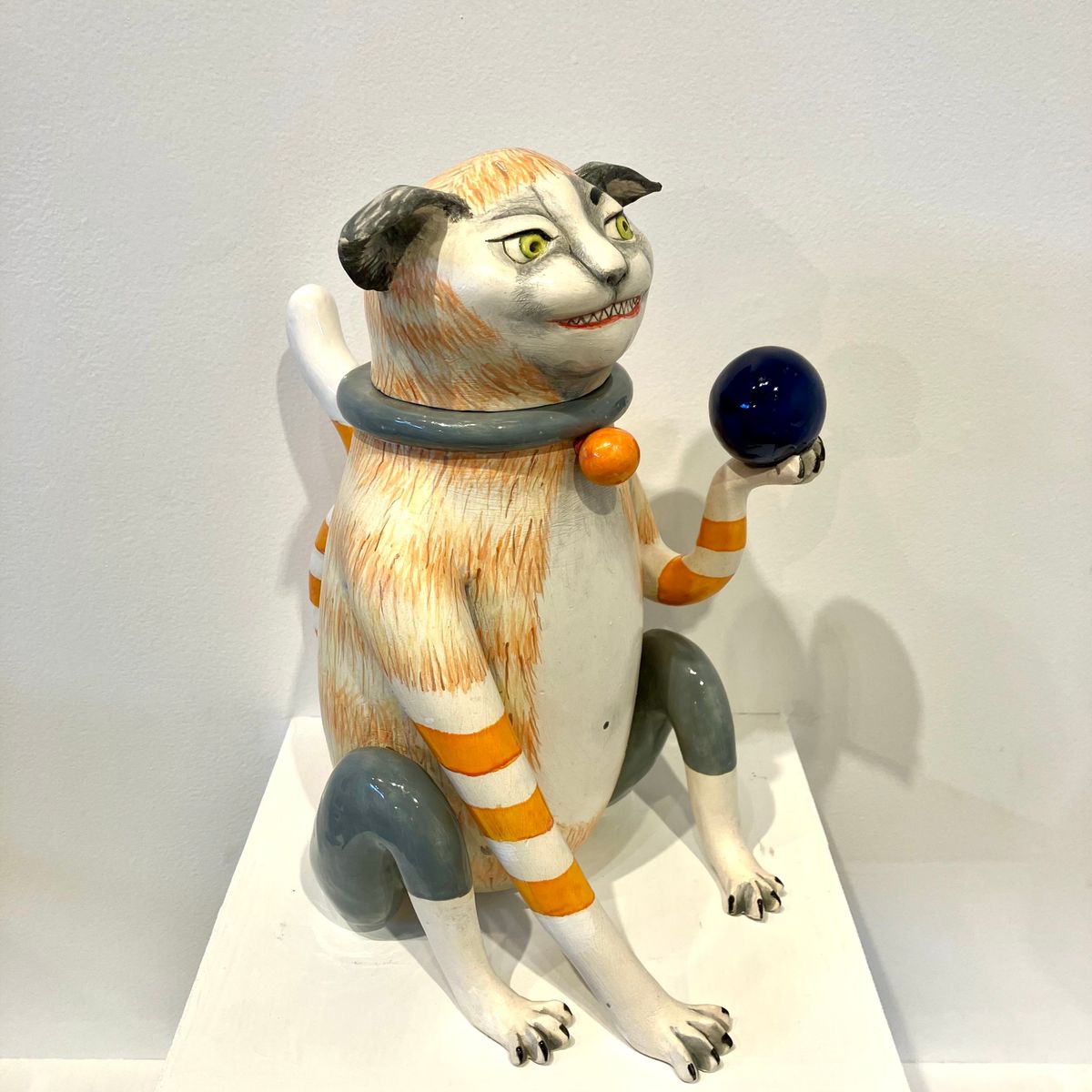

Warashina’s figures became her trademark, and her sculptures feature mostly female nudes in joyous or mischievous poses, or surreal and/or humorous situations. The meanings or social commentary vary from piece to piece – sometimes political, sometimes personal, often feminist or subversive in nature.

No matter the meaning, Warashina’s women rarely fail to delight or illicit curiosity. Warashina said she will be bringing a variety of pieces from years past to Spokane from her home in Seattle. On hand at the Marmot Art Space will be some bronzes of female figures, some birds, several prints and two “cat boxes.”

The cats and the birds are “lidded,” meaning their heads come off. “I’m not really sure why I do that. I think sometimes my utilitarian period pops out,” Warashina laughed. “I kind of like being able to move the head back and forth if I need to in a room.”

As for her more subversive pieces, Warashina questions that common interpretation of her art. “I think I’m cynical, but I don’t think I’m subversive,” she said. “It’s just that I don’t think life is one big happy thing. I just believe that in order to get through life, you have to be able to laugh.”