Two face off to be Idaho’s next state schools chief

BOISE – Idaho will have a new state superintendent of schools next year, either Republican Debbie Critchfield or Democrat Terry Gilbert.

The two come from differing backgrounds and have varying priorities, but both want to make Idaho’s education system a national leader and point of pride.

“We’re capable of being a leader nationally in programs and opportunities that we offer students,” said Critchfield, the former president of the State Board of Education.

“We don’t have to be first,” said Gilbert, a former teacher and former president of the Idaho Education Association. “But we can create a perception that Idaho has reformed its system and has become the pride of our nation.”

Idaho’s elected state superintendent of public instruction oversees and provides assistance to the state’s school districts on finances, curriculum and instruction, pupil transportation and interpretation of school laws and regulations. The superintendent also serves as a voting member of the State Board of Education and the state Land Board, chairs the board of Idaho Educational Services for the Deaf and Blind and heads the state Department of Education.

As of Jan. 1, the superintendent’s salary will be $128,690 a year, identical to the salaries for the Idaho secretary of state, state treasurer and state controller.

Here’s a look at the two candidates:

Debbie Critchfield

Critchfield, 52, holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Brigham Young University. She was appointed to the State Board of Education in 2015 and served as its president from 2019 to 2021. She’s also a former elected school board member in the Cassia County School District, where she served for 10 years, and is a former local elected library trustee.

She worked for nine years as the communications director for the Cassia school district, a position she left over the summer; worked for six years as a substitute teacher in grades 7-12; taught GED classes for the College of Southern Idaho for one year; and was twice elected to GOP precinct committee posts. She also managed the Oakley Swimming Pool for 10 years and started the Oakley swim team, serving as a coach and swimming instructor. And she served on the board and as chair of the Oakley Valley Arts Council, which puts on musical and theatrical productions at a historic opera house in Oakley, a Magic Valley town with about 800 residents.

Critchfield says she’s running for superintendent because her experience on the State Board of Education, along with serving on numerous state education task forces, “gave me an opportunity to see how policies did or didn’t work,” and she saw “some missed opportunities.“

“We’re doing a lot of things well in Idaho – let’s keep doing that,” she said. But she also sees big possibilities for change, including providing “a more relevant educational experience for our high school students,” while still stressing early reading skills and math.

Critchfield said she’s been traveling the state for the past year and a half, visiting schools and talking with businesses, parents, educators, and other stakeholders, and hears from people that they love their child’s teacher or school but think the education system as a whole is broken.

“I want to restore the value of education and what that means in Idaho,” she said. “I believe that I bring the experience … that’s needed for how we look at the modern classroom and how we prepare students for the 21st century. That’s been a focus of mine on the board. I have already established relationships with stakeholders around the state. I think that’s a very powerful part of what I do. And I know the job and I know the role – Day One, I’m ready to go. I don’t need four years to figure it out.”

Critchfield defeated current two-term Superintendent Sherri Ybarra in the GOP primary.

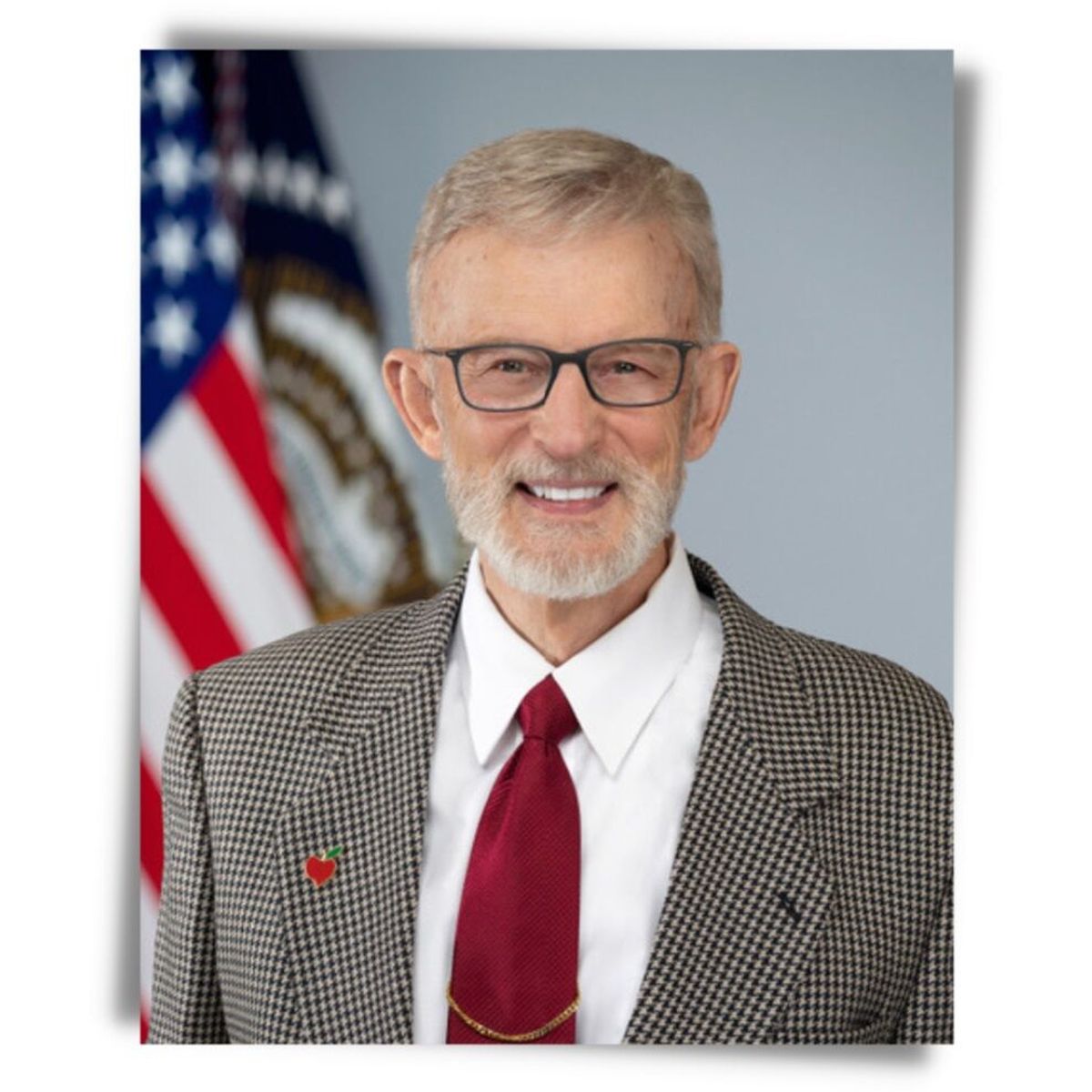

Terry Gilbert

Gilbert, 77, holds both a bachelor’s in English and a master’s in curriculum development from Northwest Nazarene University. After working his way through college, he worked for nine years as a classroom teacher in Marsing, in Aberdeen, Washington, and in Nampa, Idaho, teaching at the junior high and high school levels.

He was president of the Nampa Education Association for three years and served as president of the IEA, the state’s teachers union, from 1976-77. Gilbert also ran unsuccessfully for the Legislature from Nampa in 1977.

He then became a regional director for the North Dakota Education Association for three and a half years, before returning to Idaho to work as a regional director for the IEA from 1983 to his retirement in 2007. He served as district governor for all of southern Idaho for the Rotary Club in 2010-11. After his retirement, he became a substitute teacher in the Boise School District.

“Public education has been a lifelong passion and commitment for me,” he said.

Gilbert said he’s running because “we live in a one-party state, and that is not healthy in a democracy. … Had I not run, there would not have been a voice to counter the one-voice state.”

“My career has been to work side by side with teachers, mostly in Idaho,” Gilbert said. “So I’ve counseled them, advised them, worked with them, cried with them. Teachers are my professional family.”

“I think I understand what teachers need,” he said, “and I’m willing to work to make sure they receive what they need – not just money, but support.”

On the issues

Critchfield lists her top three issues as skill development; supporting the work of Idaho’s school districts and teachers; and funding, including “how and where we fund.”

“I want to be thoughtful and strategic about how we’re using taxpayer money for the outcomes we want,” she said.

Gilbert wants to keep public money in public schools.

“I’m very opposed to the ‘voucher-vulture’ schemes to siphon money from our public schools, the cornerstone of our democracy, into for-profit, private schools,” he said.

Secondly, he said he wants to “ensure adequate funding for public schools. And to increase funding for vocational education. I want our youngsters to have more choices. We need to improve our graduation rate in this state, and one way you do that is to give our young people more vocational opportunities that will keep them in high schools.”

Vocational and career-technical education also are a top priority for Critchfield, for whom they’re a key part of re-imagining the high school experience for Idaho students, including the requirements to graduate from high school. “We haven’t taken a comprehensive look at those graduation requirements in a very long time,” she said. “Frankly, I initiated that work as president of the State Board of Education, and then we had COVID … and that all had to pause, and rightly so.”

Critchfield said the state sets the “foundational” graduation requirements, and then local districts add their local priorities as a layer on top of those. “The area that I’ve really focused in on and strongly believe in is the career-technical education/vocational work,” she said. “I consistently hear not only from districts but from students and parents there’s no room in schedules. So these programs become electives.”

Students have to decide, for example, whether to take a CTE class or learn Spanish, she said.

“The historical and traditional pathway that we have for graduation is to go through this one door, which leads to college,” Critchfield said. “I’m not against college. … We’re very good at that.” But, she said, “For everyone else … we’re not matching the interests and goals of our students because we have a very rigid ‘this is how you’re going to go through high school’ state part” to the requirements. “And then districts try to come in and add their own interests and goals,” and pretty soon the 80 credits required to graduate from high school are taken up.

She cites an example from the Cassia district, which has a Career-Technical Center where a motivated student can take a two-year health occupations course and graduate from high school with an EMT or other certifications. But that still doesn’t satisfy Idaho’s graduation requirement for 10th grade health, she said.

“How do we incentivize kids to see that high school is relevant for them?” she asks. “I believe one of the reasons that our high school graduation rate has declined over the last eight years has a lot to do with the fact that many students get to school and think, ‘There’s nothing for me here unless I’m going to go to college.’”

She also points to a welding class she visited at Twin Falls High School that can accommodate 80 students, but turns away an additional 100 a year. “The interest is there,” she said. “How do we provide resources and support for districts to make that an important part of what’s happening?”

Critchfield’s answer is for the state to be “less prescriptive” to local districts on how requirements are met and how funds are used, allowing them to match local priorities and to recognize different ways for students to meet requirements that are meaningful for them, such as apprenticeships. She’d also pair accountability measures with those moves, to ensure results are tracked.

“We don’t have accountability in our state – we have compliance, we have data dashboards, we have demonstrations of where you ended up,” she said. “And then we are critical of districts in saying, ‘Well, we just can’t imagine why you didn’t achieve.’”

Gilbert says he wants to “establish a working relationship with every Idaho public school district by ensuring that the state department provides relevant and timely service. The state department should be a service entity to our public schools.”

He also wants to “enlist a wide variety of Idahoans to improve the literacy skills of our students,” and to “tap the fervency of our youth.” And he has plans to “organize Idaho citizens who are fervent about strengthening democracy and the lives of our citizens,” into something he’s calling “the cornerstone movement. I don’t want simply a task force. I want a movement of public citizens who care fervently about democracy and the role that public schools play.”

He said that would be “a movement that I want to create of people in the schools and outside the schools. We are a one-party state. We have essentially one voice in this state. I believe that the voice is not representative of the larger community, and I want to pull those people together in the cornerstone movement to protect public schools as the cornerstone of our democracy.”

Most of all, though, Gilbert says he wants to “keep public money in public schools.”

Critchfield said, “I have opposed vouchers. … I’m not changing my position from the primary to the general. I’ve been very consistent. I did not campaign on vouchers, nor will I. What I have said is that I am a proponent of school choice. Idaho was recently ranked 3rd in the country by the Heritage Foundation for school choice. What I believe has happened is that vouchers have become a litmus test for school choice nationally.”

So voices from outside Idaho are criticizing the state, saying it doesn’t have school choice, she said, “when in fact we have a number of ways that we are directing funds to a student-centered system.”

She noted that she’s worked on shifting funding from attendance to enrollment; the “Empowering Parents” grant program that gives grants directly to parents for their students’ educational expenses, like computers or tutoring; and supported expanding the “Advanced Opportunities” program, which pays for high school students to earn college credit, to include options for students at private high schools.

“I have been and will continue to support school choice,” Critchfield said. “What gets brought up to me, and I think is being conflated here, is public money is going to private institutions or to home school. I am open to that conversation. … I am willing to talk about anything, so long as we are first and foremost focused on our obligation to public schools and we are not taking away from that in any form.”

She noted that she raised her children in rural Idaho schools, and there’s little choice in Idaho’s rural communities, where private schools are few and far between.

“Outside of urban centers in Idaho, I talk to people all the time in rural communities who say, ‘Oh, yeah, that would be great if I had control of that money, but what am I going to do with it?’”

“I’m not looking to voucherize the system,” Critchfield said. “I’ll continue to support school choice that makes sense for us. And we want to continue to promote and fund our public schools, and I think there are ways to address many of these concerns without going to a full voucher system.”

Both candidates said they believe their backgrounds and experience qualify them for the job of state schools superintendent. Gilbert noted that after his retirement, he taught a continuing education course online for teachers through NNU on ethical dilemmas and the professional code of ethics for teachers.

“I worked during my professional career and then in my retirement to uplift teachers and to educate them,” he said.

Critchfield said after working with every level of education in Idaho for the past 20 years, from classroom substitute teacher to local school board member to the state board and state task forces, “I know how to take ideas and put them to work, and how to work with people.”

The election is Nov. 8.