‘Everyone there had to be a pretty tough guy’: Gonzaga honors four boxers who captured the university’s first and only national championship

Trophies, like the accomplishments that earn them, tend to collect dust over time. Most find their way to the back of a closet, but a chosen few get put in a glass case and, with the passage of years, get pushed to a back shelf to develop a patina that reflects a bygone era.

Accomplishments shift from a stage that sees them celebrated on posters, pennants and T-shirts to one that turns into a “Did you know …” trivia question. Especially after the giants who created it have left the stage.

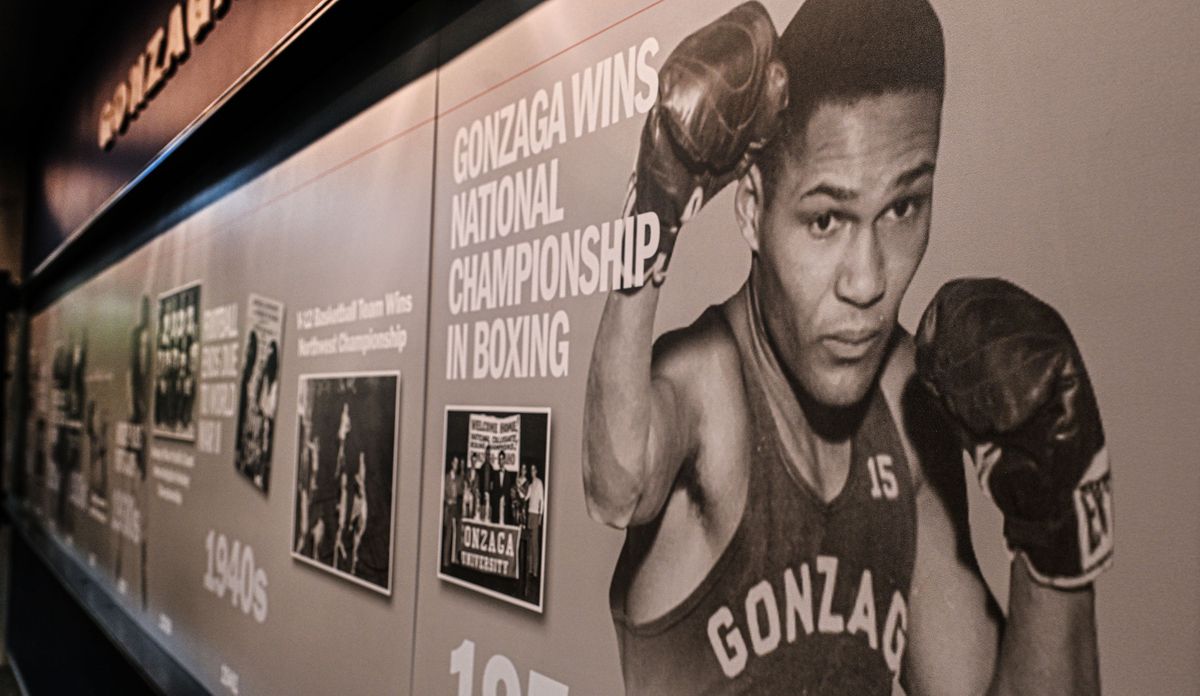

Gonzaga University is making a special effort to remind one and all of a milestone of great import: its first, and so far, only national championship.

The fact that the school has won a national championship comes as a surprise to too many fans and alumni. Not that it’s been hidden; you just have to know where to look. But 75 years does a lot in a culture that has trouble remembering where it left its car keys.

In the spring of 1950, Gonzaga sent four men to State College, Pennsylvania, the home of the Penn State University Nittany Lions, to compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s National Boxing Championships: head coach Joey August and three fighters, Jim Reilly, Eli Thomas and Carl Maxey. After Maxey beat Michigan State’s Chuck Spieser by a single point in the light heavyweight championship match, the Zags tied the University of Idaho for the national championship.

“It’s not that their national title has been forgotten,” former Gonzaga Athletic Director Mike Roth said. “When we established the Gonzaga Athletic Hall of Fame in 1988, those four men were the primary focus and we celebrated them.

“But that was a different time. Boxing, as a sport, was more popular then and really reached its peak with Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier and the Rumble in the Jungle.”

All three boxers won Pacific Coast Intercollegiate Championships in their respective weight classes to qualify for the NCAA Tournament, but perhaps their greatest accomplishment, aside from bringing home a share of the title, was simply getting to Penn State. Cash-strapped underdog Gonzaga could not afford round-trip air fare, so the Ringsiders booster club frantically scraped up the money.

When their plane landed at Geiger Field, the four men were met with a horde of adoring fans who hoisted each of them on their shoulders and carried them from the tarmac.

“I know my dad really enjoyed that whole Gonzaga boxing experience,” Carl Maxey’s youngest son, Bevan, said. “He enjoyed the camaraderie he had with his teammates and his relationship with his coach. I think he appreciated that whole boxing environment because everyone there had to be a pretty tough guy. And I think he really appreciated that whole community.

“I can’t imagine what it must have felt like to come home to that kind of a welcome.”

What adds depth to their national championship is the fact that all four men lived lives of service. Their lives were accented by their time at Gonzaga, not defined by it.

•••

Joseph Michael August is most often remembered as Spokane’s long-time supplier of beer. In many ways, that was just his day job. His lasting impact was as an unflagging sponsor of area athletics. For many years, you would have been hard-pressed to find a youth sports league that did not feature teams sponsored by Joey August Distributing.

August always tried to minimize his philanthropy, saying over the years that he was just putting something back into his hometown. But a local writer once observed, “Joey was putting back long before he ever started taking out.”

The Spokesman-Review’s John Blanchette summed up the essence of August after he died in November 1996:

At the warehouse on Alki, or the old one on Trent, sales reps from the beer and wine companies would come calling on Joey August.

If they were new to the territory and didn’t know Joey, introductions could be memorable.

“Where’s Joey’s office?” they would ask.

“Well, he doesn’t really have an office,” someone would say.

“So where can we find him?”

“He’s over there.”

“Where?”

“Over there. Taping that guy’s ankle.”

Over the years, they all came to Joey – jocks with joints old before their time and salesmen with new brands to peddle, coaches in need of a team sponsor and ex-coaches in need of a job.

The fifth-grade spelling champ one day, the women’s bowling team the next.

Joey August indulged them all.

Who will indulge them now?

In 1987, August donated $177,000 to area sports – equivalent to almost a half million in today’s dollars.

What gets lost is the fact that August was an accomplished boxer in his own right, winning several AAU championships and a Pacific Coast collegiate boxing championship at the University of Idaho, which won three-time NCAA team champion. He is credited with 14 professional bouts as a lightweight between 1931 and ’38, posting a record of 11-2-1 with more than half of his wins coming by way of knockout (six) with a single loss via knockout.

He was Gonzaga’s lone boxing coach, taking teams to the national tournament in both 1950 and 1951. The program was canceled in 1952 after the NCAA made changes to eligibility and a schedule became limited. The NCAA ceased sanctioning the sport in 1960.

Though heartbroken that his team was gone, his contributions to boxing never flagged.

He was a referee for 65 professional bouts, including a bout at Seattle’s Sicks’ Stadium between former heavyweight champion Ezzard Charles and Harry Matthews on Aug. 31, 1956. His final two bouts as a referee were both at the old Spokane Coliseum, featuring Northwest heavyweight Boone Kirkman – a first-round TKO of Leroy Birmingham and a third-round knockout of Wayne Heath, both in 1967.

And he was a judge for eight professional bouts, all in the Spokane-Coeur d’Alene area. His final bout was Spokane boxer Lenny Hahn’s unanimous decision over Rudy Barro on Oct. 23, 1980, at Kennedy Pavilion.

“If you remember, before we built the McCarthey Athletic Center, we had our old baseball field, Pecarovich Field, which we renamed August/ART Stadium,” Roth said.

•••

James Patrick Reilly died in 2017 after 88 years after years of unfailing support for Gonzaga and amateur boxing. Pound-for-pound, Reilly was as tough in the ring as they come, winning Pacific Coast titles at 130 pounds in 1949 and 1950, and he was the unsung hero of the national championship effort.

Reilly lost a disputed decision in his 132-pound lightweight semifinal bout in 1950, but there would be no title without his valuable points.

He was a respected coach and counselor to area boxers for more than two decades. He coached several nationally ranked amateur boxers over the years and was the long-time, unpaid director of the Inland Empire Golden Gloves Tournament.

•••

When Eli Thomas died on his 93rd birthday in 2022, he was the last living link to the national title.

Thomas won back-to-back individual national titles for Gonzaga – as a 152-pound welterweight in 1950 and as a 165-pound middleweight in 1951 – while posting a 34-0 record over his final two years. He also won a Montana-Wyoming Golden Gloves Championship

“Eli Thomas deserves a medal for guts,” August said. “He won his second title under the handicap of a continued illness that kept him underweight all the time.”

Born in Butte, in 1929 as the youngest of 11 children, Thomas served in the U.S. Army, stationed in Germany, for two years after he graduated and boxed for the Sixth Army team.

Eli and his family settled in Santa Clara County, California, in 1964 and established Eli Thomas Menswear, which has been a successful business in San Jose for six decades. An impeccable dresser who favorited Italian suits, perfectly knotted neckties and impeccably polished shoes, he whole-heartedly believed in the potential of the people he met and frequently used his network of friends, family and customers to help people who impressed him favorably – helping many businesses succeed through his support and mentorship.

Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to the California State Athletic Commission, where he advocated for stronger safety standards to protect boxers.

He served as a member of the Board of Trustees of New College of California, was a member of the San Jose State Spartan Foundation and was a member of the Board of Directors of the San Jose Police Activities League.

In addition to the Gonzaga Athletic Hall of Fame, he was also inducted into the Butte Sports Hall of Fame and was chairman of the San Jose Sports Hall of Fame.

He and his wife, Dorothy, were married for 63 years, raised nine children and had 15 grandchildren.

•••

Carl Maxey didn’t set out to be a boxer at Gonzaga.

Born to a single mother in Tacoma in 1924, he was raised as an orphan in Spokane before he was taken by a Jesuit priest, Father Cornelius E. Byrne, to live at the Coeur d’Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart Indian School in Desmet, Idaho, where he excelled in the classroom and as the most valuable player on the baseball, basketball and football teams.

Fr. Byrne introduced Maxey to the boxing ring, where he won his first amateur bout as a 13-year-old, beating a 33-year-old opponent.

After graduating from Gonzaga High School in 1942, Maxey joined the Army during World War II with the intention to become a pilot, but the Army Air Corp barred African Americans. The racism and injustice he and others experienced as a private in a medical battalion in the Jim Crow South sparked an intense social awareness.

Maxey entered the University of Oregon on a track scholarship in 1946, but he returned to Spokane and Gonzaga University to both box and study law.

Tall and intimidating, the formidable King Carl was undefeated (32-0) as a light heavyweight and went into the championship bout at the 1950 NCAA Tournament to face Spieser, a member of the 1948 Olympic boxing team who was looking to cement the title for his Michigan State Spartans.

But Maxey won the bout by a single point to share the title with the Vandals.

August used few words to describe Maxey: “In a class by himself.”

For a young Black man in 1950s America, earning the respect Maxey found in the boxing ring was an important matter.

“I don’t know if my dad ever considered continuing his boxing career,” his son said. “But he didn’t, although I do think it influenced how he approached things.

“That was the thing about him. He wasn’t out to make friends; he was out to make change.”

Maxey was the first African American to graduate from the Gonzaga School of Law in 1951 and the first to pass the bar exam in the Inland Empire before launching a 46-year career fighting for social justice and against discrimination in all its forms.

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, he volunteered in Mississippi to help Blacks register to vote, free Black activists from jail and march alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Back in Spokane, he helped members of the NAACP by handling pro bono cases and five U.S. presidents named him to serve as the chairman of the Washington State Advisory Commission to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Maxey’s career in the courtroom was much like his career in the ring: He was as direct as a left jab setting up a powerful right.

The Maxey Law Office he founded with sons Bill and Bevan and continues to serve clients, with grandsons Morgan and Mason Maxey joining the firm.