Weak dollar isn’t all bad

NEW YORK — American company Tupperware Corp. is rooting for the dollar to stay weak, while Irish crystal maker Waterford Wedgwood PLC wants the opposite. The reasons why show how the dollar’s fall to a record low against the euro boosts some companies but bruises others.

Orlando, Fla.-based Tupperware, best known for its snap-top plastic food containers, gets almost half its sales from Europe. When that revenue is converted back to dollars, it translates into higher reported profits, as rich euros buy an ever-increasing number of dollars. In the most recent quarter, the currency effect accounted for almost 30 percent of the company’s $18.6 million net income.

Waterford Wedgwood, which makes Waterford crystal and Wedgwood china, depends on the United States for about half its sales. But with each dollar it brings home to Dublin, Ireland now worth only about 77 euro cents, the company has been forced to slash costs at its factories to stay competitive.

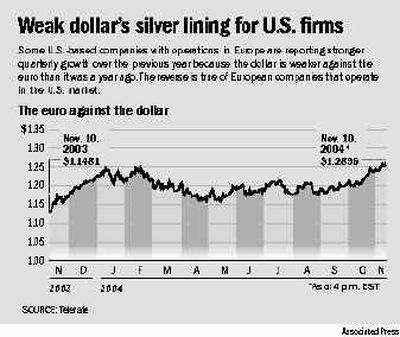

The dollar hit a new low against the euro on Wednesday and has lost 10 percent of its value against the currencies of the United States’ major trading partners since Mid-May, figures from the Federal Reserve show. The euro, launched in 1999 as the common currency for Germany, France and 10 other European nations, is on a tear, up 57 percent since October 2000.

Some analysts think the dollar’s decline is being engineered — or at least blessed — by the Bush administration, which wants to help U.S. companies boost overseas sales. If so, it may be working: The Commerce Department reported Wednesday that exports of goods and services grew 0.8 percent to a record $97.5 billion in September. Even so, the overall U.S. trade deficit topped the $50 billion mark for the fourth consecutive month.

The dollar’s decline carries the risk of sparking inflation as foreign goods become increasingly expensive. And former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin suggested this week that the administration could be playing with fire, and noted that unless politicians in Washington get serious about reducing the federal deficit, an acceleration of the dollar’s decline could cause “serious disruptions in our financial markets.”

At the current rate, the United States has to attract $5 billion of working capital every day to finance the current account deficit and American investments abroad, said C. Fred Bergsten, director of the Institute for International Economics in Washington. The current account deficit is made up mostly of the country’s trade debt, but also includes foreign aid and money immigrants send home.

That’s why Bergsten’s predicting further declines. “Everyone in the market knows the dollar has to come down a lot,” he said. “People are starting to run for the exits.”

For now, the benefits of a cheaper dollar are mostly a positive for such mainstay American companies as International Business Machine Corp., Amazon.com Inc., Levi Strauss & Co. and Estee Lauder Companies Inc. whose overseas sales help boost their earnings in dollar terms.

By contrast, European companies that sell goods and services in the U.S. hate the weak dollar, because every time they exchange their hard-earned dollars for euros, they lose money.

Companies like French media telecommunications giant Vivendi SA, Finland-based sports equipment maker Amer Group PLC, German sporting goods maker Adidas-Salomon AG and Finland’s Nokia OYJ, the world’s largest mobile phone maker, have recently reported earnings or sales shrunken by the strong euro.