Still reeling, Brits cope with losses

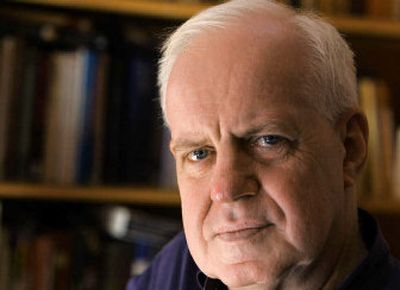

LONDON – John Falding finds comfort in talking, even though the memories haunt him: the phone call from his girlfriend, Anat Rosenberg, to say she was on a bus to work. Then screams, then silence.

Amrit Walia wanted to “go out guns blazing” to retaliate for the death of his 26-year-old schoolmate, Anthony Fatayi-Williams. Calmer now, he is thinking about ways of reaching out to angry young Muslims before they strap on explosives.

A month has passed since four suicide attackers blew themselves up on three London subway lines and a double-decker bus, killing 52 passengers, and those left behind are struggling to come to grips with a day that started out in morning rush-hour routine and ripped their lives apart.

The dead and those who mourn them are a multiethnic, multifaith profile of London. Rosenberg was an Israeli Jew; Falding is English and not Jewish. Fatayi-Williams, born in Nigeria, was a Roman Catholic with a Muslim father; Walia is a Sikh.

Shahara Islam, British-born of Bangladeshi descent, was a bank cashier who attended Friday prayers at her mosque and liked to shop at trendy clothes stores. There was Behnaz Mozakka, a woman from Iran, and Karolina Gluck, a woman from Poland, and Giles Hart, a 55-year-old Englishman honored posthumously by Poland for his support for the anti-Communist Solidarity movement.

There were stories of cruel happenstance, such as the woman who called a relative to say she had emerged safely from the Tube, only for fate to catch up with her minutes later on bus No. 30. Her route to her death was much the same as Rosenberg’s.

‘The terrible irony’

“It is just so mindless, the whole thing so pointless,” said Falding, 62.

He was sitting alone in his central London apartment, surrounded by traces of his girlfriend – photos of her posing in a Roaring ‘20s glamour outfit, dents from her stiletto heels in the wooden floor.

“The terrible irony,” said Falding, “is that it happened here” – in peaceful London, not in her native Israel, where the fear of suicide bombings was burned into her mind.

For some relatives, the agony was compounded by having to wait a week or more for confirmation as investigators picked through the carnage deep underground and in the mangled hull of the bus.

Walia was at first hopeful because a missed call from Fatayi-Williams showed up on his cell phone timed off at 9:57 a.m. – after the bombing. Then he found out the phone’s clock was 20 minutes fast.

When the worst was confirmed, he said, “I beat the wall, threw up, cried.”

He said his dead friend was “everything to me” – a large, muscular man who looked after the circle of friends, “as odd as this sounds, like a woman in a way. He was the one that cared about us, that believed in us all and kept us boys together.”

Now he’s thinking of setting up a foundation to send out the message that violence isn’t the answer.

“These terrorists are our age; we listen to the same music; we can see what they are about even if we don’t understand it,” said Walia. He is 26. The bombers were three Britons of Pakistani descent and a Jamaican, aged from 18 to 30.

‘Terrorism is not the way’

For the world, Anthony’s mother became the face of grief-stricken London as she appeared on TV, awaiting confirmation of her son’s death.

“Which cause has been served?” Marie Fatayi-Williams asked. “Certainly not the cause of God, not the cause of Allah. … Anyone who has been misled, or is being misled to believe, that by killing innocent people he or she is serving God should think again because it’s not true. Terrorism is not the way.”

“Why? I need to know, Anthony needs to know,” she said.