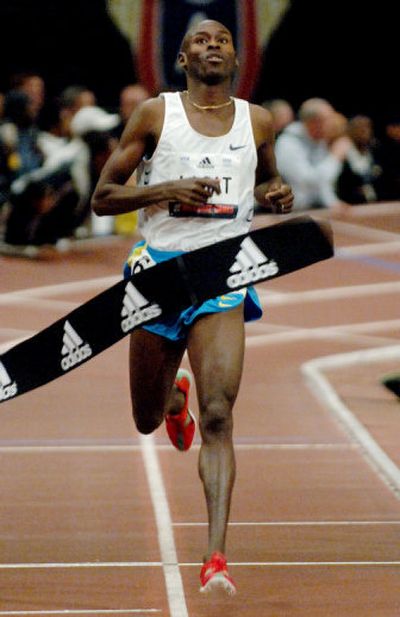

Lagat chases history

Bernard Lagat checked the weather forecast for the Palouse this weekend and shivered from the memory of December training runs.

“I used to wear two hats,” he said. “What do you call them? Toques? And none of those running gloves would work so I’d have to go the mall and buy those heavy- looking ones, almost like boxing gloves.”

Going from equatorial Africa to the sometimes subarctic Pullman winters was an enormous leap of faith for Bernard Lagat, regrettably the last of the splendid Kenyan distance runners who left large footprints all over the track and field record book at Washington State University.

So, too, was the achievement that brings him back to town today.

Lagat is the school’s special guest at the Cougars’ basketball doubleheader this afternoon, a chance to acknowledge the twin gold medals he won last August at the IAAF World Track and Field Championships in the 1,500 and 5,000 meters – and that he did it as an American citizen. The first steps toward both of those outcomes began in Pullman, where he also met his wife, Gladys, where he connected with a coach (James Li), where he developed allegiances. For instance, though he now lives and trains in Tucson where Li works at the University of Arizona, the TV room in Lagat’s four-bedroom home is done up in Cougar crimson.

Now the steps resume for one final mission: the Beijing Olympics.

Predictably, Lagat is being pressed on his intentions for the 2008 Games: Will he double as he did in Osaka?

Though he was the first runner to win both events in the World Championships, a reprise in Beijing would put him in other-worldly company. Paavo Nurmi won the 1,500 and 5,000 in the 1924 Olympics; 80 years later, Hicham El Guerrouj did it in Athens, narrowly outkicking Lagat in the shorter race.

“It is too early to say – I’m going to keep all my options open,” Lagat said. “My focus is on the 1,500 because I feel I have unfinished business in that race.”

A gold medal, he means, to go with the silver from 2004 and the bronze he won in 2000. But he’s also talking about his place in the sport’s history, which to this point has been inextricably entwined with El Guerrouj – and not as equals. There is no resentment – Lagat admired his Moroccan rival both as a sportsman and as a competitor. He allows that his motivation for trying the Osaka double was to see if he could emulate what El Guerrouj had done three years earlier.

“I’ve never ‘won’ anything – I’ve always been in the shadows of El Guerrouj,” Lagat admitted. “And when he retired, people were asking, ‘Who is the next one?’ And I wanted to take it. But when I run in the (European) circuit, I get beat by some guys. And people are thinking, ‘Hmm, Lagat is not the one. Another new kid from Kenya or somewhere will be the one.’

“But there’s never been one person who has been able to take the 1,500 the way El Guerrouj used to do. Part of me winning these two events puts me in a different category and that is what feels good.”

There were many subplots to Lagat’s story in Osaka.

It was his first time representing the U.S. in international competition, having not run under any nation’s flag for three years per legislation enacted by the IAAF (with Kenya insisting Lagat serve the full term, not at all pleased by a wave of expatriates running for the new countries). He was again back in the shadows – this time cast by the great American hope of the mile, Alan Webb, whose final ascension to superstar was supposed to come in the 1,500 until he ran a race full of tactical miscalculations.

And then with one gold in hand, Lagat was all but handed his second one when the 5,000 field plodded through the first 10 laps – just asking to be run down by a canny veteran with a half-miler’s speed. His split for the last 800 meters of the 5K race was nearly the same as it had been in the 1,500.

“I almost celebrated with two laps to go,” he said. “I had to compose myself because it was mine for the taking.”

Hearing the American anthem played at a medal ceremony for distance races is a rare thrill, yet there has been considerable debate over Lagat’s change of citizenship and its impact on U.S. competitors who have been routed by the Africans for years. Yet Lagat said he began seeing a feistier attitude from American runners when he was still competing for Kenya.

“The mentality is entirely different,” Lagat said. “They’re not satisfied with being the best in the country – they want to be the best in the world. You see it in Alan Webb, beating all of us. A lot of them have said I’ve set the bar and it’s not easy to copy what I’ve done. But it’s do-able. I want to be the person who has that responsibility, to set it, and when they beat my mark I’m going to be the first person who will be happy.

“This has been fantastic for me. When I represent the U.S., it’s not just because I acquired citizenship. My heart, my soul, everything is for this opportunity. I have a duty to run well.”