Mahre’s race

Most guys pushing 50 want to lose weight or lower their handicap. Phil Mahre, arguably the greatest ski racer in American history, wants to qualify for the U.S. national championships next season at 50, for a shot at the youngsters on the U.S. Ski Team.

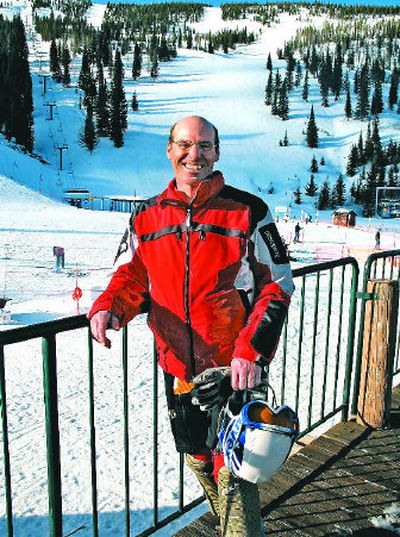

Mahre came to Schweitzer recently for the Selkirk Cup, a western regional event sanctioned by the International Ski Federation (FIS). He raced two slaloms and two giant slaloms in his campaign to qualify for nationals in 2008. In the slalom, he was fifth overall.

Ripping his second slalom run, Mahre’s smooth, refined style clearly set him apart from much younger skiers who descended before him. In a helmet and speed suit he looked fit and finely tuned like an athlete in his prime.

Mahre lives on a ranch near his hometown of Yakima. Between races, with his twin brother Steve, he runs Mahre Training Center, a prestigious ski camp in Deer Valley, Utah. He’s confident he will land sponsors to allow more time for training next season.

His return to competition is creating quite a buzz in ski racing. James Cochran, a U.S. Ski Team racer, told the New York Times in January he had no doubt Mahre is legit.

“It sounds like he’s going to make nationals,” Cochran said. “Hopefully, he won’t beat us.”

Mahre wanted to make it clear his age-defying foray into the spotlight isn’t what many people are calling a comeback.

“It’s more of a personal goal,” he said. “I don’t have any desire to make the ski team. I’ve been there, done that. The goal is to make the U.S. nationals and be there next year when I’m 50. But I’ve always left my goals open-ended. If I make the nationals and something else comes from that, we’ll see how far we can take it. I’m having fun.”

Mahre is the 1984 Olympic slalom champion. He is the first American to win the overall World Cup title and he did it three years in a row, 1981-83. He retired from ski racing in his prime after the 1984 season.

“When I was competing in my 20s, people would ask me how long I could do it and I said probably until I was 40,” he said. “Then I promptly retired at 26. It was time to move on. My priorities were no longer in ski racing. So I got out of it and raised a family. But now the youngest is 18 and the two oldest are out of the house. The last couple of years I’ve been kicking it around. The 40s have passed me by, but why not the 50s?”

Mahre said he was also inspired by the success of Ted Ligety, a member of the U.S. Ski Team who came out of nowhere at 21 to win Olympic gold in the combined at Turin, Italy, in 2006.

“The kid was off the radar two years before the Olympic Games,” he said. “He went from unknown to Olympic gold medalist. That inspired me to go out and have some fun at it again.”

Mahre insists his aspirations don’t include anything beyond the nationals at 50, but his reference to Ligety, and the fact the 2010 Vancouver Olympics are just a few years out, give away an intense competitive fire still burning within.

“If I were to go to nationals, great things happen, and I put myself in a position to be named to the ski team, the Olympics are only two years out,” he said. “I don’t have aspirations for going to the Olympic Games. But if that opportunity presented itself, it would be hard to say no thanks. Hey, 26 years later, why not?”

Mahre’s pedigree meant nothing starting from scratch with no FIS points and no sponsors in the Golden Rose Ski Classic last June at Mt. Hood. Ski racers enter competition with 990 FIS points. Race results subtract from the total. Skiers with lower points earn earlier starts and faster conditions.

“This year is a posturing year for me,” he said. “It’s a year to whittle my points down so I can get my starting numbers where I can be competitive. My first race at Mammoth I started in the 80s, then I went to Park City and started 121. It’s next to impossible to do anything from there. Now my start numbers are getting down to where I can be competitive.”

Before racing at Schweitzer, Mahre said his FIS points were down to 70 in slalom and 50 in GS. It’s been easier for him to move up in GS because changes in technique from 1984 to 2007 are not as drastic. But he enjoys the greater challenge of the slalom more.

“The equipment has made it easier, but my learning curve is growing again. The sport is so much faster than it used to be,” he said. “Courses are set much more down the fall line. Gates are farther apart. Skis carve. You don’t have to slide so you’re never braking. You just go faster and faster.”

Until this year, Mahre never used today’s 165cm slalom skis – 40cm shorter than his 1984 vintage. He trains to separate his body from a mind conditioned to do things a different way for 40 years.

“We used to have a big up movement, especially in giant slalom,” he said. “We came up and we stepped. You steered the ski into the fall line and then carved the bottom half of the turn.

“Now you can just tip it up on edge and rip it. When I do that I feel like I’m just standing there twiddling my thumbs. I think, ‘c’mon you gotta move.’ So I move, get a flat ski; lose my edge angle and it all falls apart.

“That’s the big struggle for me, becoming consistent. One run everything will flow together and another run I’m back 23 years.”

For an athlete who once reached the pinnacle of his sport, Mahre revels in the experience of traveling on his own dime, learning new technique and fighting from the back of the pack.

“It can be frustrating, but fun because it’s a new challenge,” he said. “Out here I’m still getting beat up by kids, but I have my moments. I’m young in the sport again.”