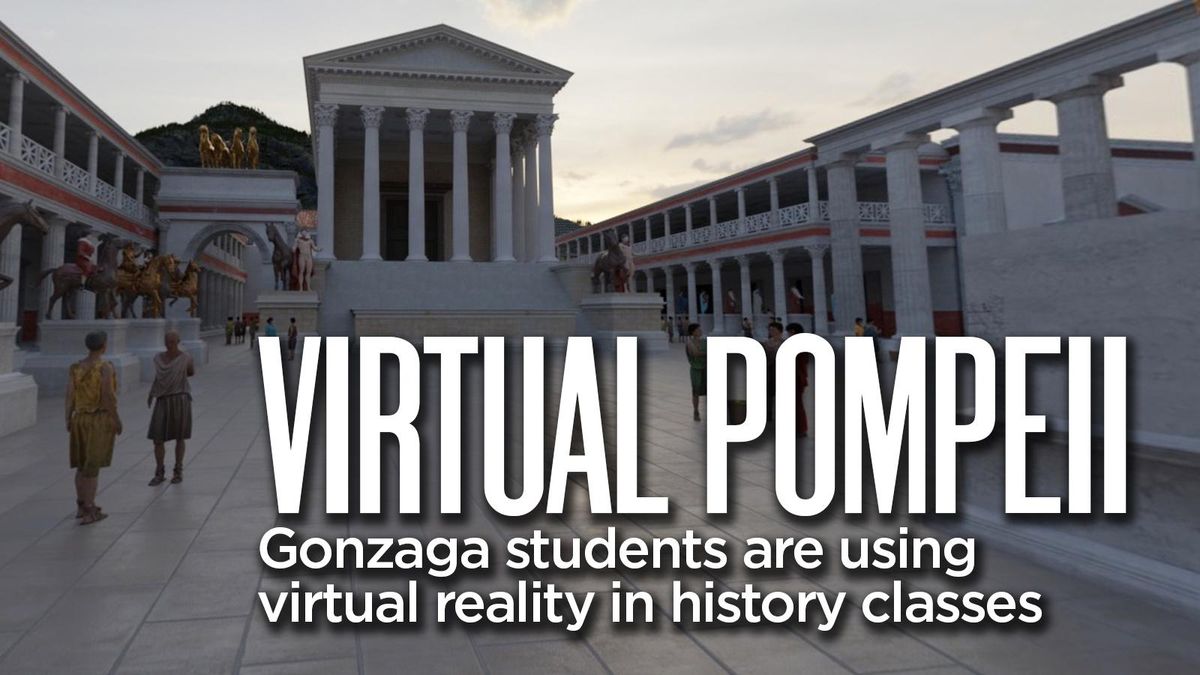

Virtual Pompeii: GU students time traveling in class using Lithodomos VR technology

Gonzaga University students Jonas Hyllseth and Reid Martinez use their cellphones and virtual reality to explore the digital re-creation of a house in ancient Pompeii during Andrew Goldman’s history class on Oct. 4. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)

Thanks to virtual reality, history students can tour Pompeii much like they’re passing through it before Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD.

Gonzaga University history professor Andrew Goldman, an archeologist, is testing new tools in a class on Pompeii, an ancient Roman city buried by thick volcanic ash. For an Oct. 4 study, students used their smartphones, $5 cardboard viewers and VR technology tied to archeological evidence.

Up popped colorful, 360-degree images of a prominent resident’s atrium room in the House of the Faun – so named for a statue. About 20 students also viewed a Pompeii bakery and then ventured into the city’s forum where the Temple of Jupiter sat.

“Hello, sacks of flour,” said student Will Georges while looking around the ancient bakery. Georges worked with the class of 20 students to answer Goldman’s questions about life in Pompeii, such as the layout of living spaces and sources of water, before the volcano’s destructive eruption.

“They’ve re-created a long-destroyed city and let you walk through it and see what it was like to live there,” Georges said. “The forum was the biggest shock. We always thought of Pompeii as a little town, well-preserved, then we saw a massive forum.”

This year, Goldman is trying out classroom applications for new technology being developed by Lithodomos VR, an Australian company.

Lithodomos has created nearly 400 virtual-reality “experiences” of ancient cities, mainly for tourists, but also for educational uses. Goldman said he hopes to use Lithodomos’ VR in other history classes as an educational tool.

Goldman first heard about the VR archeological company about two years ago when he was in Turkey doing a project on the Black Sea. He was visited by his friend Simon Young, Lithodomos’ founder and also an Australian archeologist.

“I was pretty wowed by the technology of Lithodomos VR,” Goldman said. “I asked him if we could be one of the trial runs of actually building this into a classroom. He loved the idea, so he and I collaborated.”

“This company has professional archeologists, so they go through a very rigorous process of looking at the archeological evidence, ancient paintings or carvings of the buildings and literary sources. These reconstructions are about as accurate as they can be.”

“It’s completely immersive, and you can see 360 degrees.”

GU’s College of Arts and Sciences provided a grant toward the project for educational use in its classes. Goldman said he wants to take students beyond “the wow factor” by asking them questions based on the viewpoints about how people lived in ancient times and what shaped the civilizations.

The GU professor first used Lithodomos VR in an ancient city course taught last spring. In the past, virtual-reality technology and equipment were bulky and expensive, Goldman said, but that’s changing. Today, many students own a smartphone, and a number of them are familiar with VR because of gaming.

In the near future, Goldman said he hopes GU history students can download an app for about $20, comparable to an inexpensive textbook, to view the VR images for course questions.

“One of the reasons why we felt we could do this is the technology has advanced to the stage where you’re downloading an app, then you put your phone into these phone-ready cardboard lenses that are very inexpensive,” he said.

“What it has meant is we can try using virtual reality in the classroom at a low cost to the students.”

Based on feedback from this past spring, Goldman said Lithodomos has refined certain aspects such as the use of QR codes to scan for a VR playlist. Meanwhile, Goldman has worked on how best to bring the tool into classes.

“I’ve designed all kinds of assignment using different VR viewpoints,” Goldman added. “My favorite is in the ancient Colosseum of Rome.

“There are about a dozen different viewpoints from individual places across the Colosseum. You can see it from the position of a wealthy person, from the nosebleed seats and underneath where the animals were caged.

“So you can explore it not as tourist today in the ruins, but how it would have looked in antiquity.”

It stimulates questions about the workings of ancient cities and how different classes of people experienced them. “Oftentimes, we have accounts of the wealthy,” Goldman said. “This lets us stretch into the corners a bit more.”

Other questions can explore how structures were built, what historical sources were used for viewpoints and about facts known or still unknown. Ancient Rome had sophistication such as culture, running water and well-planned public spaces, he said.

“We use these experiences as a way to think about how accurate are these, how real, what do we know about an ancient cityscape?” he said. “For the students, it also opens up their eyes to the colors and fabrics of the ancient world.”

Some 3D models of ancient civilizations now can be viewed on computers, but many university history classes are still using textbooks, he said.

Unlike looking at a flat image in a book, the students gazed up, down and all around at the House of the Faun. They talked with Goldman about the vast living spaces, rich building materials and artwork that included a mosaic of Alexander the Great.

The students learned that the atrium’s small rectangular pool was a water source from collected rain descending from an open roof space above.

Damian Aranda, a student from Oregon, thought the images were more realistic than looking at pictures in a book.

“Pictures only can show you so much as far as details,” he said. “I thought the experience was amazing because in VR, it’s like you’re the person at the time seeing it with their eyes walking through Pompeii. Although it’s not identical, it’s very close.”