Developer Rob Brewster returned to Spokane to rebuild his reputation, but now those efforts appear largely stalled

Formerly the McKinley School, the building from 1902 is seen behind chainlink fences at 117 N. Napa Street on July 31, 2019. This is one of several dormant properties owned by Rob Brewster. (Libby Kamrowski / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Empty seats are hard to find on a Thursday evening at the modern food hall downtown.

Vendors line the walls with an array of food: pizza, burgers, ramen, bibimbap, ice cream, you name it. Long shared tables dominate the large, open room’s center. At one, a family surrounds a variety of dishes, splitting them. Professionals gab over an after-work beer. A couple share an ice cream cone.

That’s in Portland, where Rob Brewster helped to open the Pine Street Market, a bustling urban space that’s half food court, half swank restaurant.

Compare that to Spokane, where Brewster, a Spokane native, proposed nearly two years ago to do the same thing on Riverside Avenue.

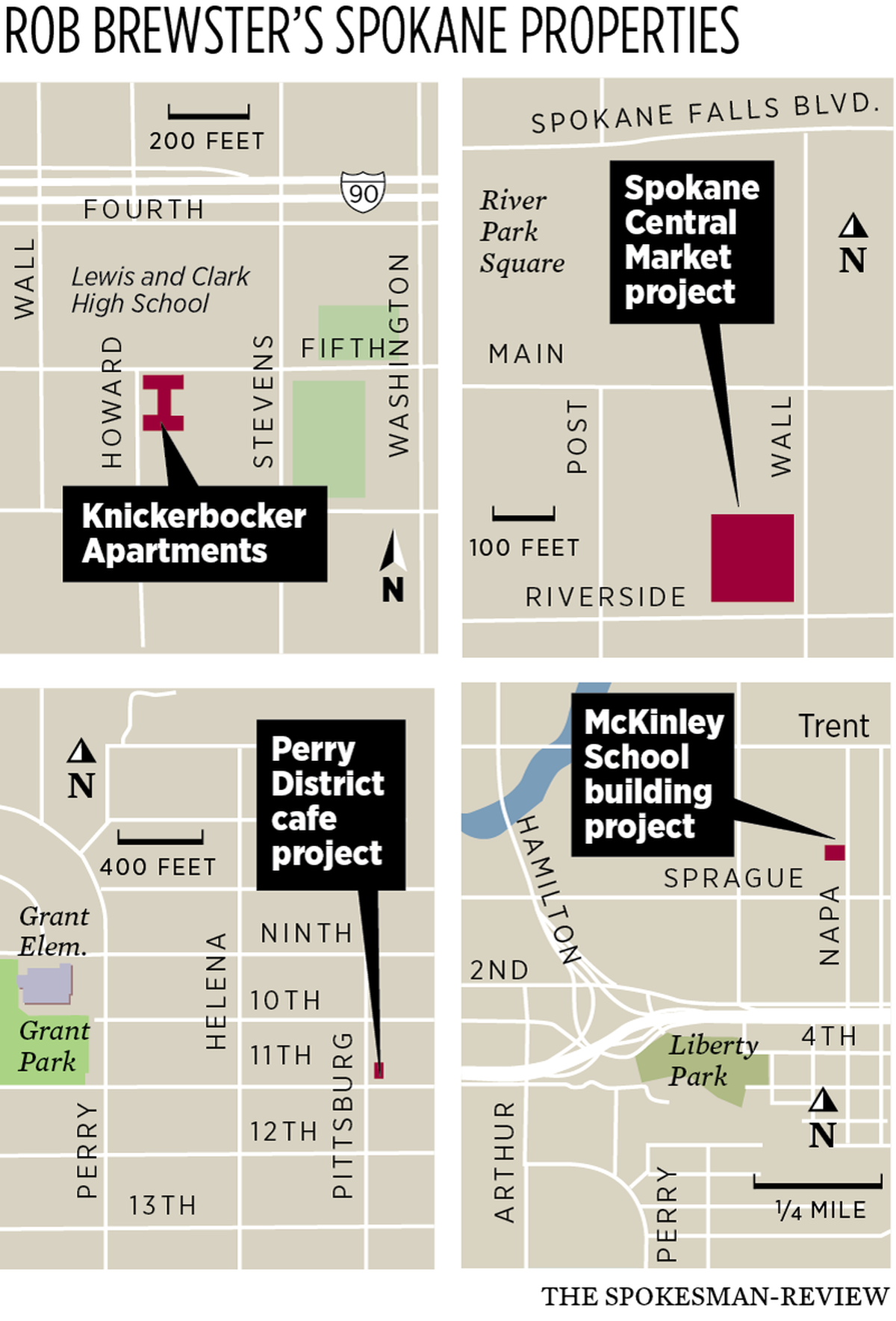

That space is empty. Interior demolition moved quickly in the first days of 2018, stripping away false walls to reveal original features dating back to 1919. Then, just as quickly as it began, work stopped on the first floor of the former Umpqua Bank building at the corner of Riverside Avenue and Wall Street.

It’s not the only project that Brewster touted as being just around the corner, while the corner appears miles away.

A café in the South Perry district sits vacant, its power shut off from unpaid bills and $4,300 in unpaid property taxes, in the red and two years behind.

A third project, the renovation of the historic McKinley School into a brewery, began with interior demolition but sits far from finished. Until Thursday, it had four years of unpaid property taxes totaling more than $43,000. Most of that was paid after Brewster was questioned about the delinquent taxes by The Spokesman-Review.

A fourth project by Brewster that stands in contrast to the others is the continuing rehabilitation of the Knickerbocker Apartments near Lewis and Clark High School. The three-story, 28-unit building has been undergoing a top-to-bottom renovation since 2010, when the building’s previous owners, Mary and Eric Braden, began to overhaul the 108-year-old building. They completed renovations to 20 apartments before selling the property to Brewster for $2.7 million in April 2018. Renovation of the remaining eight apartments continues under Brewster.

These four projects were to be a vindication of sorts for Brewster, who fell from grace as Spokane’s wunderkind developer in 2013, after he filed for bankruptcy protection and moved to Seattle.

A tarnished reputation wasn’t something he was used to. In the late 1990s and first decade of the new century, he was lauded as a developer who could cobble together complicated funding mechanisms to save historic buildings, most notably with his first project, the Holley-Mason building, saving it from decades of vacancy and ruin. Within five years, he employed 70 people and owned more than $45 million worth of real estate in the Inland Northwest, comprising half-a-million square feet.

Then the recession came, followed by Brewster’s bankruptcy.

Three years later, in 2016, he dove back into Spokane real estate and development and purchased historic properties with an eye toward renovation and reinvention – the same game plan he had before his collapse. Brewster has said in the past his history has no bearing on what he does now. But as the projects remain unfinished, it’s hard not to connect what’s happening with what happened then.

Brewster’s even back in court again, following litigation he initiated in June 2019, facing allegations that he lied about the amount of money he had, as well as the skills he possessed, to get his projects completed. Contractors on one of his projects said the work they did went unpaid. And one potential food hall tenant said he’s waited long enough and is searching elsewhere for a new location.

With bills unpaid, utilities shut off and the passage of at least six months since any permits have been issued, Brewster said he hasn’t over-promised or under-delivered. He says his new empire of historic buildings won’t collapse. History isn’t repeating itself, Brewster suggested.

“They’re all moving along,” said Brewster, who responded to texts but not phone calls. “All good progress.”

Formerly the McKinley School, the building from 1902 is seen behind chainlink fences at 117 N. Napa Street on July 31, 2019. This is one of several dormant properties owned by Rob Brewster. (Libby Kamrowski / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

An incredible gamble

Brewster’s luck ran out during the recession, but it began at birth.

He’s the son of an orthopedic surgeon and the oldest of three in a well-to-do South Hill family. He also knew from an early age what his future held.

A 2004 profile of Brewster in The Spokesman-Review said he’d spend his childhood days at the family’s Spirit Lake cabin “building a little town in the woods” and putting “his younger sisters in charge of the grocery store and the bank, where they printed play money.” Brewster, however, ran the make-believe real estate office.

After attending Roosevelt Elementary and Lewis and Clark High School, Brewster went to Santa Clara University in California, earning a bachelor’s degree in political science. He purchased his first property while still in college – a house on Mission Avenue near Gonzaga University that cost $105,000. He bought it using money he borrowed from his family.

It was dominoes after that.

He refinanced the Mission house, and borrowed against it to buy an old warehouse with a friend for $100,000. They fixed it up and sold it two years later for $135,000. In the mid-1990s, he read in the Washington Post about townhouses for sale in Washington, D.C. He moved there and, with money from his father and the sale of the Spokane warehouse, bought the properties. He rebuilt the townhouses and rented them out for a few years.

“They were crack houses before,” Brewster said of the townhouses in 1998.

He bought another old townhouse in the nation’s capital and worked with a London businessman to convert it into 11 condominiums in D.C.’s Logan Circle. The units sold out before the renovations were even complete.

In 1999, at the age of 29 and with development experience, he returned to Spokane.

His first project was the rehabilitation of the Holley-Mason building, 157 S. Howard St., which had sat empty for 30 years. Brewster purchased the $475,000 building through seller financing, borrowing money from the building’s owner and paying it back month by month. By this time, he had persuaded administrators at his alma mater, Lewis and Clark, to hold classes in the Holley-Mason from 1999 to 2001 as the school underwent a two-year renovation – an agreement that would generate $1.2 million in rent.

Using the promise of rental income, as well as $1 million worth of tax credits from the building’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, AmericanWest Bank loaned Brewster $5 million.

“It was an incredible gamble that paid off,” Gary Livingston, then-superintendent of Spokane Public Schools, told The Spokesman-Review in 2004. “The financing was complicated, and the risk was great. Here’s this young, 30-ish kid with no money and we’re going, ‘Oh my goodness.’”

‘It’s going to take risk-takers’

Untangling the finances of real estate developers is never an easy task, but the 15-year-old profile of Brewster gives some indication of what role his family played in his growing real estate empire. Brewster said his father co-signed on some loans when he was getting started, and was a partner in some D.C. projects. His parents loaned him $10,000 for one of his earliest projects, as did each of his sisters, who pooled money left over from college funds when they attended state schools.

With family dollars seeding his ambition and savvy fueling his rise, Brewster seemed unstoppable.

He bought the Montvale Hotel with his father. He opened the 137-bed Brewster Hall in downtown Cheney, an Eastern Washington University student residence, in September 2002. In 2004, he considered buying The Local Planet, a Spokane alternative weekly, before saying he changed his mind after he “woke up at 3 a.m. thinking real estate, real estate, real estate.” The paper folded that year. He owned the Hutton building. His plans for the Havermale block, nearly an entire city block bound by Riverside and Sprague avenues between Bernard and Browne streets that he owned, included building a $40 million, 32-story building called the Vox Tower.

At the age of 34, he said he envisioned running for Congress someday. But his passion was clearly real estate.

“I get so tired of people talking about the things they want to do and, maybe I’m naive, but why would I waste my time just babbling about something?” Brewster said in the 2004 profile. “If I’m going to choose to live in a community, then I sure as hell want this to be the best community possible. I don’t want to live in a mediocre place. If I can do something that can make it more fun, make it more interesting, make it successful, that’s how I see it. It’s going to take risk-takers. I don’t think I’m the only one.”

The risk piled up and, in 2012, began collapsing.

That summer, clinging to a mountain of debt, he lost the Holley-Mason building to Prudential Financial. Then he filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on the Hutton, and listed debts on the property and its holding company of $3.9 million. At the time, the property was valued at around $3.4 million, according to bankruptcy documents.

The following February, he filed for bankruptcy protection on the Montvale, which had business debts and obligations of more than $1 million. By this time, a host of financial judgments had been filed against him in state court. Among them were a $2 million judgment in San Juan County, a $1.7 million judgment in King County and a $917,000 case in Spokane County.

As he prepared to pack his bags and leave for greener pastures in Seattle and Portland, Brewster didn’t blame the economy or his own decisions as a developer, but Spokane itself, which he said had “lost most of the momentum.”

“Name a Spokane business that is cool and really growing robustly,” Brewster said in a 2012 Inlander story. “Maybe Green Cupboards. Maybe?”

Green Cupboards was an online eco-product retailer that changed its name to Etailz in 2013. The Spokane Valley company was acquired in 2016 for $75 million by Trans World Entertainment Corp. of Albany, New York, but reduced its staff by 20 percent earlier this year after its parent company reported $14 million in losses.

From ConoverBond to Revonoc

Time heals and, after some success in Portland and Seattle, Brewster came back to Spokane with a splash. With a Seattle-based investor group, he paid $950,000 for the historic McKinley School in the East Central neighborhood, which he planned to pattern after the McMenamins chain of pub and entertainment venues.

Gone were his acidic descriptions of Spokane. “I think it is one of the coolest buildings in Spokane,” he said of the McKinley in 2016. He praised East Central, saying it had “texture” and “stands on its own.” A year later, he said the neighborhood was “one of the coolest neighborhoods in town, one of the most fascinating districts in the state.”

Next up was his $6.5 million purchase of the Umpqua Bank building downtown. Within three months, Brewster was filing plans to convert it into a multitenant restaurant space with a shared, open hall for dining. The initial plans filed with the city listed a doughnut shop, taqueria, a lounge, a brunch diner, ramen house, burger joint and two shared kitchens.

The same month he filed food hall plans, he bought a small, 94-year-old corner grocery store in the South Perry district for $83,000. About two weeks after the sale, Brewster filed plans with the city for an extensive renovation of the building, which had been used as a residence for 45 years. The application said construction would start “ASAP.”

Brewster was suddenly a player again in the Spokane real estate game. His name was the same, and well known. The companies he operated under, however, weren’t. Before he had left town, Brewster operated under numerous companies, the most notable being ConoverBond and Selkirk Trading.

In their place is a new network of corporations, but at the center of them is Brewster.

Brewster v. Vessel

The old grocery store on 11th Avenue and Pittsburg Street in the Perry district was making the most obvious progress before work stopped.

After Brewster bought the building, the project cleared a hurdle in May 2018, when the city’s hearing examiner said commercial use was allowed in the building, which had been used as a residence since 1974. At the time, Vessel Roasters said they were moving in.

Steve DeWalt, who was the public face of the project for Brewster, said he expected the coffee shop to be open by the end of June 2018.

Instead, the building sits vacant, with construction incomplete and no longer underway. In July, the city shut off the utilities due to lack of payment and late charges. According to the Spokane County Assessor’s Office, two years of property taxes are unpaid, equaling $4,269.

In a text, Brewster said the café has “just been a slow opening.” He said the café would be open by Sept. 15. He said Vessel no longer has plans to open there. “They decided not to expand. We have someone else. Better,” he said.

In court documents, however, Brewster and Vessel tell a more complicated story.

It began in December 2017, when Sean Tobin, Vessel’s owner, met Brewster and DeWalt. Tobin had opened Vessel on North Monroe Street in 2016 and was doing well financially. North Monroe was about to undergo a massive reconstruction project, and he thought the roadwork would “significantly impact the profitability” of the Monroe café. He “needed to open a second location by June 2018 to supplement the cashflow that would be lost during the Monroe Street construction,” according to court records.

Brewster floated the idea of moving into the Perry district building, and Tobin bit. Brewster made “repeated representations” that it would be ready by June 2018, according to court documents filed on behalf of Tobin. He said he was “adequately capitalized to complete the project timely and efficiently,” and said he and DeWalt were “skilled in their field and could adequately perform the buildout.”

So in March 2018, an eight-year lease was signed.

June came and went. In December 2018, Vessel said it no longer wanted the space, noting lack of progress and blown deadlines. On June 20, 2019, KSS Holdings, the legal owner of the building, filed a complaint in Spokane County Superior Court against Vessel for breaking the lease, kicking off the legal battle.

Vessel and Tobin punched back. All the assurances Brewster made about the space turned out to be wrong, the response alleges, and Brewster “knew or should have known that these representations are false or misleading.”

What’s more, Vessel alleged that KSS Holdings, Brewster and DeWalt knew the building wouldn’t be ready in time, that they didn’t have the money or the skills necessary to actually renovate the building.

Tobin alleges that Brewster didn’t pay Vanguard Contracting and Summett Construction, two contractors that worked on the project. Both companies confirmed being unpaid by Brewster.

Ryan Kelly, owner of Vanguard, confirmed that he was owed money, but did not want to go into details. “The public records pretty much show what happened and we settled afterwards,” Kelly said.

Because of the debt, Kelly placed a lien on the property, and the city canceled the permits. After their settlement, the lien was released in January 2019.

Summett also confirmed that it is still owed money for work it completed in January, as are its subcontractors.

DeWalt denies nonpayment.

“Did that contractor tell you that they overbilled us by $30,000?” he said of Vanguard. “We told them we’re not paying these invoices.”

DeWalt also denied not paying Summett.

“I don’t know what he’s waiting on. We’ve paid him everything he’s due,” he said. “We paid him a significant amount of money for that project. … He never filed a lien, which he was more than legally entitled to. The onus at that point is on him to pay the $50 and file a lien.”

Tobin, Vessel’s owner, would not comment on the litigation.

In a text, Brewster said Vessel’s claims were “typical legal bs.”

“We are suing Vessel because they failed to take the space,” he wrote. “I certainly don’t think it’s newsworthy and don’t need a rent conflict tried in the court of public opinion.”

DeWalt said another tenant has been found, and plans to have “an autumn opening.” But he couldn’t quite explain why the city shut the utilities off this summer after months of nonpayment, or why the property was two years behind in property taxes.

“Those are turned on. I think I just hadn’t paid attention,” he said. “I don’t handle as much of the accounting.”

‘I see no delays’

Brewster and DeWalt also had trouble explaining the four years of unpaid property taxes on the McKinley School. As of Wednesday, the Spokane County Treasurer’s Office listed $44,200 in delinquent taxes stretching back to 2016.

In a text Tuesday evening, Brewster said, “Thanks for the reminder on the taxes. They’ve been paid.”

DeWalt echoed that Wednesday. “Those are paid up,” he said.

Were they paid Tuesday?

“I think so,” DeWalt said.

Were they paid in response to The Spokesman-Review asking about them? “I’m not sure.” Why weren’t they paid for four years? “I do not know, honestly.”

The treasurer’s office confirmed that a payment for McKinley’s property taxes was processed Thursday, Aug. 29. Taxes for the first half of 2019 remain delinquent, with an outstanding bill of $5,766.81.

Beside the property taxes, city utilities were shut off at McKinley in February 2018 for nonpayment and late fees. Electric service is also off there, according to Avista.

Regardless, Brewster and DeWalt blamed the city for any delay of the project.

Brewster has long said that any construction on the McKinley School had to wait until the city was done building a 180,000-gallon sewer and stormwater tank in the ground adjacent to the building. The project finished recently a year behind schedule because high groundwater made construction more difficult than expected.

Still, the tank is done and DeWalt couldn’t give a date when work would begin.

“As soon as we have finances lined up. Hopefully pretty soon. Once we have the financial components of the project all lined up, the construction component will take about 12 months,” he said. “We’re actively raising the equity portion of it. Talking to lenders.”

Brewster, on the other hand, said work there will begin in October. Like his previous projects, the renovation of the McKinley School depends on tax credits aimed at spurring rehabilitation of historic buildings.

He’s also in line to receive money from the city of Spokane to the tune of $165,665 as part of the Projects of Citywide Significance program. The city money – which will only reimburse Brewster for some of the construction that happens in the public right of way like water and sewer mains, sidewalks and street trees – will only be delivered to Brewster when the project is complete and if he has complied with all public works requirements governing prevailing wage, bidding and other rules. The City Council is scheduled to vote on approving the money in October.

Such estimates for a food hall opening don’t come as easily. The food hall – the Spokane Central Market – was a complex project, which entailed converting a 1990s-era bank into an open space dining hall. In January 2018, Brewster gave about 40 people a tour of the building, told them demolition would be done in two weeks, and said the food hall would be open sometime in the summer of 2018. At the time, he said about 20 potential vendors had signaled interest, many of which signed letters of intent, he said.

Eighteen months later, the food hall remains empty. Brewster blames the city, saying it caused an eight-month delay in the project by requesting a “change of use” permit for the first floor.

“It was totally unnecessary but we complied with it,” he said.

Since receiving that, he’s been signing up tenants, noting it’s “our market hall policy to only open with 80% or more tenants. We have not reached that yet.”

“We are getting close,” he said. “Opening up with fewer is a death trap for these food hall projects.”

Neither Brewster nor DeWalt would name any potential tenants, nor say what percentage occupancy they’ve achieved.

“I can’t share specifics,” DeWalt said. “I’d rather you get that information from Rob.”

Although the building is without a food hall, it does have other tenants. ENGIE Insight, formerly known as Ecova, moved in this year and occupies the entire third floor. One known potential tenant for the food hall is Taste Cafe, which closed its Howard Street location in August 2018 to move into the food hall.

“When Rob approached us about coming, we immediately liked that idea and committed to moving Taste Cafe into the food hall,” said Jim McCurdy, who owns the restaurant with his wife, Mary Anne, and son, Mike. Designs were drawn up, and McCurdy believed they could be in the food hall in September or October 2018.

From the closing through February, McCurdy said he received calls every day asking about the cafe’s reopening. Then the calls petered out. McCurdy is still supportive of the food hall, but he hasn’t heard from Brewster since the spring and has begun searching for new locations.

“We haven’t been in contact for some months. We just don’t know where the project stands at this point in time,” he said. “We were very committed to moving in at that point in time and a year later we still really like the idea of a market. Given the time frame and all, we’ve been exploring different locations. We’d like to get Taste up and running.”

Sill, Brewster denies there’s any delay to his projects.

“What delay are you talking about?” he wrote. “I see no delays.”