Summer Stories: ‘Ashes to Ashes’ by Julia Sweeney

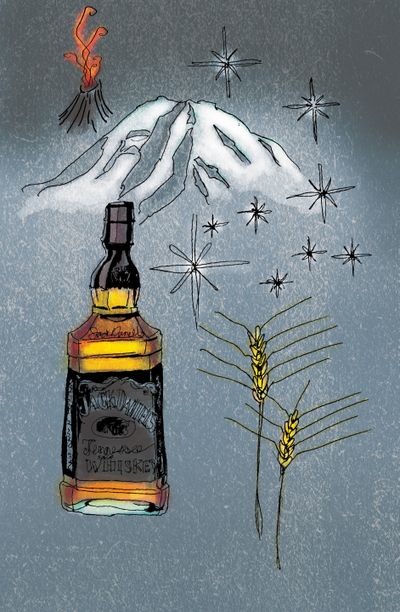

It was a Sunday morning in May, and Ben had just left Angela’s dilapidated Seattle apartment building in good spirits. After a year of flirting, yearning and maneuvering (and with the aid of some Jack Daniels added to the espresso they sipped while playing chess at Last Exit on Brooklyn the night before), he’d finally gotten Angela to invite him home. A stupefying soup of oxytocin, dopamine and seratonin swirled through his veins.

He could hardly control his face from smiling as he closed the apartment building door behind him. Wisteria blooms hung from above the entryway to the otherwise neglected courtyard, and the scent was powerful. Even his vision seemed keener. On the sidewalk, he looked up to her second-floor window. She stood there, looking down on him, wearing her “Quadrophenia” tank top, her dark, long hair cascading majestically around her muscular shoulders. Juliet looking down on Romeo. The sun, shining right into her window, obscured her face, and Ben put a hand to his forehead to shade the bright rays. Maybe more like Moses looking up at Yahweh.

He mimed tipping his hat to her with a slight comic bow – “Thank you, M’Lady.” He couldn’t tell if she could see him. Maybe that was weird. Maybe he shouldn’t have done that. She was older than him – 27 to his 20; he would have to watch out not to appear ridiculous. He grimaced and looked away, silly – too silly? That had happened, too, the night before. A joke she’d made. He wasn’t quite sure if she were laughing with him or at him. How comfortable was he being teased? He guessed he would have to accept that kind of thing, being with a clever woman who is seven years older.

He turned and looked across the street at his ’68 VW bug, the passenger door held on by an orange bungee cord. Mary Kate. She’d done that. Mary Kate was Ben’s high school girlfriend back in Spokane. He tried to teach her how to drive a stick, and she’d landed them in a ditch. They both laughed so hard they waited several minutes before getting out to survey the damage. Then they laughed even harder. Now that was funny.

But that was three years ago. Now he was a college man who lived in Seattle, and he was seeing an older woman. He liked the sound of that. I’m seeing an older woman. My girlfriend is older than me. It sounded titillating. Older woman implied sexual expertise. Nice. But was she his girlfriend? No, but she could be. Couldn’t she? Was she? He felt he could make it happen. Couldn’t he?

He swerved away from this uncomfortable uncertainty and let himself feel the full onslaught of the thrill of success. Yes! He remembered being on a roller coaster some years back, that sensation in your body as you come off that first climb and descend to earth, only to see a bigger hill ahead. Giddy. That was the word.

Ben and Angela both worked at the Varsity Theater in the U district, a block or so from the University of Washington where Ben was a junior studying astronomy. He sold popcorn and tickets; she ran the projector upstairs. The theater played indie films, and they played for a long time. “Quadrophenia” had run for eight months, then they began playing a German film by Rainer Werner Fassbender, “The Marriage of Maria Braun.” (When Ben looked back on this time, which he often did, he began to see that the transition from “Quadrophenia” to “Marriage of Maria Braun” tracked his own concerns. Rock ’n’ roll mayhem giving way to the desire to couple up and hunker down. The Who to whom.)

Ben was attracted to Angela from the moment he met her. Her demeanor, even the way she moved, demanded a certain privacy. She exuded a kind of solitary, unaccompanied essence that hung in the air around her like Pigpen and his dust cloud. Only not smelly. In fact, the opposite.

Ben was generally gregarious and chatty. He liked to connect to people. Certainly, the other guys at the dorm weren’t spending all their time figuring out how to worm their way into the mind of a girl like Angela. No one understood his attraction to Mary Kate in high school, either. She, too, was a step off from the rhythm of her peers, a mostly solitary person. Her piety and quiet nature made her come off as imperious at times, but Ben could see through it to her sincerity. Mary Kate’s high school nickname had been “Mother Superior.” It’d been hard for Ben not to tease Mary Kate back then when they’d finally connected physically – those powerful, awkward early collisions – and sing to her “Mother Superior jumped the gun.” Mary Kate would absolutely not have laughed at that one.

It occurred to Ben that both Angela and Mary Kate were loners and that maybe he had a type. And what was Mary Kate doing right now? Was she really joining a convent like she’d said in her last letter? Was he the only guy who didn’t realize she’d always been committed to a much more important guy, that guy in the sky? Was his rival God? Why did sleeping with Angela open the door to thoughts about Mary Kate, lurking in the wings of his awareness? It was as if she was always ready to bound onto center stage.

Maybe it was because he could still feel Angela’s body under his fingers. And it made him feel a vague lingering guilt, like he had betrayed Mary Kate. Even though he had not! Absolutely had not! They were unambiguously not together anymore.

Ben glanced at his hands gripping the steering wheel as he drove south. They looked remarkably like his dad’s hands, which seemed creepy to notice in this moment, his dad burrowing his way into his sexual encounters. Ben noticed that he had the same callus on his forefinger and the split fingernail on his ring finger. It must have come from all that working with dough at the doughnut shop, and certainly not from counting the dough, which was meager and hard won. His dad had owned and personally run the Donut Parade, a modest coffee shop up on Hamilton and Illinois. He became known for his maple bars. The family lived a couple of blocks away.

Angela’s body, athletic and muscular, was nothing like Mary Kate’s, who was curvy and soft. Angela’s body also held surprises. She had a tattoo of Mount Rainier on her back. Mount Rainier! What kind of girl had a tattoo of Mount Rainier? Angela said, “In 20 years time, tattoos will be ubiquitous, especially on women.” Who said 20 years time? And ubiquitous? What was she, British? No, she’d told him, she was from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In the small wee hours, as they lay together spooning, his head resting on her back, in the snow at the summit of Mount Rainier, she’d told him some of her story.

Ben tried to remember. She had, for the first time, become somewhat chatty, just as the exhaustion of the evening was gallivanting through his body calling him to sleep. Angela had had a difficult time at home growing up. Her mother had a string of alcoholic, explosive boyfriends. Things got bad. She considered ending her life. She stopped talking to anyone about anything. One day she passed a used-book shop with a box out front. For a dollar, she picked up “A Year in Paradise” about some Shmoe living for a year, in 1920, on Mount Rainier with his wife. The book catapulted her out of her world. She decided to get a tattoo of Mount Rainier on her back. She knew a tattoo artist. She would do it. The mountains enduring, unchanging permanence answered deep needs. She literally wanted Mount Rainier to have her back. And of course, then she had a new mission: to move to the Pacific Northwest.

She’d met a guy while still in Michigan, Dave, a few years older, and an actual geologist. He was studying the volcanic rock that rimmed the Upper Peninsula, and she had been wandering around the scrappy woodland near her house. They dated on and off for several years. He was in Seattle, too, working at Mount St. Helens waiting for the expected eruption. He had done geological work on Mount Augustine in Alaska. “My grade school was named St. Augustine’s,” Ben thought but fortunately did not say. It would’ve been the kind of comment that would’ve betrayed how sloppily he was listening to her.

And anyway, Ben didn’t like to think about this guy, this older guy who was an actual scientist and not flunking out of astronomy at UW like he was. Ben concentrated on the part of the story where they weren’t seeing each other anymore. When Ben learned her ex had been a vulcanologist, he imagined him Spock-like with pointy ears. But as he slipped his jeans back on in the morning, he saw a picture, and he was blond. Huh. So, they both had blond exes.

Angela was funny. When he sheepishly explained he was flunking his optics class, she said, “Well, that’s not gonna look good.” And when he’d said he thought she was shy because of her difficult past, she said, “Hey, there’s only room for one projectionist in this room.” Clever. You had to be on your toes with her, alert. It made him feel honored that she’d let him in and made him feel uncomfortable in ways he didn’t entirely understand.

Ben stopped at the light at 50th and University. It was remarkably clear, like Seattle was previewing summer, and had sent the rain clouds offstage. People had an extra energy, seemed more alert. Green was bursting through everywhere.

As he waited for the light to change, Ben wondered if he should invite Angela to come with him this summer to Loon Lake, where his parents had a cabin. He imagined what it would be like to present his family with this attractive older woman with a tattoo on her back (of Mount Rainier!) as his girlfriend. He could see his sisters in their bikinis and his mother in her flowery skirted suit and his father in his knee-length trunks. And Angela coming out of the cabin, towel draped off her hand, walking into the water, turning, and yes, they would see it. His sisters would think it was cool, his mother would make some awkward comment, and his dad would say nothing. Dad was quiet because he was that sort. But, there was another reason he’d be quiet.

His dad was dead. It was hard to keep remembering that. His dad had died only a year before. It was remarkable how loud his father had become now that he was dead.•

Mary Kate was Ben’s only official girlfriend. She took Catholicism quite seriously unlike most of the other students who moved easily between the cultural Catholicism of the school and the modern world. She was open about her convictions, and so she was especially hard to court. Fortunately, she wasn’t an evangelist. Or a scold. They’d met at Gonzaga Prep, junior year, the first year the school admitted girls. Mary Kate’s former high school, Holy Names, had just closed its doors. She lived with her aunt a few blocks from school. Her parents were wheat farmers on the Palouse an hour south. Ben and Mary Kate had driven down together one Saturday in the late summer, the wheat stalks brimming and bowing supplication under the sun. They stopped at Steptoe Butte and climbed to the top and yelled out “Amber waves of grain!” to the yellow-gold world around them. They tried to summon the wind so they could catch the waves. Just after that was when he tried to teach her to drive, and Mary Kate promptly wrecked the car. He’d never had a strong desire to fix that door, and now he drove around Seattle with Mary Kate’s orange bungee cord around the passenger door. A talisman of their union.

Ben saw Mary Kate’s bedroom at her parents’ farm. Cut-out images of saints adorned the walls like they were movie stars. The crown molding staged multiple Infants of Prague, like some sort of celestial orphanage for royalty. Where many girls had posters of Ryan O’Neal in their bedrooms, Mary Kate had hung one of Pope John Paul II proudly above her desk. Her eccentric devotion appealed to Ben.

In their senior year, up at Loon Lake, Mary Kate was helping Ben close up the cabin for the winter. After consuming a stale loaf of bread and a bottle of red wine (Ben did not make a joke about the body and blood of Christ), things went farther than either of them expected. The next week, Mary Kate explained patiently to him, and with admirable resolve, that while she was glad it happened, it wouldn’t happen again. And, if she were pregnant, she would have the baby. He’d figured. A few anxious weeks of sweet misery followed. If they had to marry, he wouldn’t have been able to go to college. He’d just learned he had gotten a scholarship to the University of Washington. If they married, he would’ve had to start working full time with his dad at the Donut Parade.

It’s true, Ben suddenly thought, that if that had happened, he would’ve been there for the last two years of his dad’s life as the cancer came back again and again. He felt a pang of … what? Equal parts relief and regret. The family understood. After all, he was off becoming an astronomer.

•

Except he wasn’t becoming an astronomer. He was failing out of his program. It was the math that got him. He liked looking at the stars at night, naming the constellations, thinking about how small we were. But it turned out the field of astronomy was seriously about math, and Ben was not very good at that. He’d just failed two of the three required math classes. Multivariable calculus didn’t have a variable that allowed for incomprehension. The scholarship was going to end when his GPA was revealed. Ben didn’t know if he wanted to recommit and retake the math classes. Why didn’t someone tell him astronomers spent all their time on graphs, databases, following algorithms? He’d lost his interest when he understood what the day-to-day life of an astronomer would be like.

Ben got close to the theater and began to look for a parking space, which he knew would be easy since it was Sunday. The first matinee was at 2 p.m. In “The Marriage of Maria Braun,” the title role is played by Hanna Schygulla, who reminded Ben of Mary Kate, strongly and unnervingly: her wheat-colored locks, her pointed nose, the comfortable nature with which she held her body, especially how she moved her hands. But mostly it was the tenor of her voice.

The first time Ben was invited up to the projection booth, when Angela’d asked him if he could bring her some popcorn, he’d been struck by the darkness. It seemed fitting that Angela would have a job where she could work with most of the lights off. The carbon-arc projectors were ancient, and the clicking sound of the film’s sprockets created an eerie soundscape that mirrored his beating heart. At one point, when they were whispering, in midconversation, Angela took a cigarette out of her pack, opened the side panel on the projector and lit it off the arc lamp, her eyes on Ben the entire time. He involuntarily gulped; she was astonishingly beautiful and in command. The word “erotic” floated across his prefrontal cortex. Yes, that’s the word. Erotic. Ben thought for a second he might literally swoon. That would have been a disaster.

And then be recalled his high school English teacher, Mr. O’Connor, who had a thick working-class Boston accent. While guiding the seniors through a section of the book “Dangerous Liaisons,” he described a passage as “erotic.” At first, many in the class thought he’d said “erratic.” It became a recurring bit among his friends, “That film was so very erratic.” “He wrote both poetry and erratic literature.” “I’m into erratica.”

Remembering this worked . As he beheld Angela, standing there at the projector with her cigarette, half her face lit up and the other half shadowed, he didn’t blush, or perspire visibly, or break the intensity of the moment with chatter. He took it in in its fullness, and he stored away this image like a secret gift he’d gotten just for him. From behind Angela’s head, through the small square opening for the projector lens, Ben could see the movie screen in the auditorium. Hanna Schygulla was jumping up on some old gymnastic parallel bars in a boozy club where her character, Maria, is applying for a job. She says, “You might not need anyone apart from me.” That line was a cue to Angela to prepare the next reel, and she shifted her gaze from Ben to the other projector, readying it for the transfer.

“You might not need anyone apart from me.” Ugh. Ben wanted Mary Kate to leave him alone. How long would this movie play at this theater? Was Mary Kate trying to send him a message through Hanna Schygulla? Absurd. However, he had gotten that letter from her, which he hadn’t answered, telling him that she was going to enter a convent after graduating from Gonzaga University. One might ask why Ben was looking for messages cryptically sent to him through Hanna Schygulla when Mary Kate was sending him actual messages.

Ben drove past the theater and saw a parking spot across from the street right next to the University Book Store. As he pulled into his space, he realized that people on the sidewalk were looking up in the sky to the south. Getting out of his car, he looked in the same direction.

Mount Rainier had smoke swirling around its top, like a meager brown toupee. An older guy on the sidewalk, looking in the same direction, said, “It’s Mount St. Helens. She finally blew.” “Oh. Wow,” Ben replied and stood there, transfixed by the billowing ash. Rainier stood right in front of St. Helens, like one actor upstaging another. The man continued, “Did you feel the earthquake this morning?” “No,” Ben replied, becoming mesmerized by the site of smoke thundering into the sky. “Yeah, not many people did. 8:30 a.m. I guess that’s what finally opened her up.”

Ben tried to remember more of what Angela had told him about her ex, Dave, and wondered if he were up at the mountain, and if the phone ringing that morning, which she’d ignored, was from him. Ben grimaced, understanding that he hadn’t paid enough attention. He sighed and looked at the sidewalk. What did he really even know about her?

When he raised his eyes again, heavenward, he could see the smoke and ash were blowing east even while much of it still hung in the air cradling Rainier like a cloud of unknowing.

In their senior year religion class, Mary Kate and Ben read an anonymous 14th century mystical classic, “The Cloud of Unknowing.” The basic idea was that one should not spend time thinking about God’s particular attributes or actions, but the way one can truly know God is to surrender your mind and ego to an “unknowing” and thereby possibly glimpse, or feel, or thrill to the true mysterious nature of the Almighty. Mary Kate had been deeply moved by it; Ben had seen it as another way for the church to dodge scrutiny and avoid critical thoughts about God’s existence. They had argued, he’d made jokes about it. Maybe too many jokes. Sometimes, Ben thought, admonishing himself, he didn’t know when to be quiet. Mary Kate found his reaction to the text disturbing and revealing. This turned out to be the beginning of the end. She couldn’t be with someone who didn’t at least, on some level, respect her religious devotion. And Ben couldn’t fake the kind of faith she admired. So, she had gone off to Gonzaga University to study theology, and he had gone off to the University of Washington to look heavenward in his own way.

Ben couldn’t move from his spot on the sidewalk – more and more people were stopping and looking south and into the sky. He realized he was trembling. Even though he knew the lava was not headed toward him, the image of the eruption was deeply disturbing. He felt afraid, even terrified. The sensation of fright came from somewhere deep inside him, like an automatic fear of snakes, buried in ancient generations only to reveal itself now. A part of him was thinking how silly it was that he was shaking and scared, but another part was enveloped in the terror and in utter awe at the destructive power of the earth, of nature, of mountains. Adrenaline surged through his veins, overtaking the dopamine and serotonin and leaving him with his heart beating loudly, so loudly he wondered if others could hear it. He took a deep, slow breath trying to calm himself. And then this chattering voice inside him, this justifying explaining part of his neocortex, took over and wouldn’t stop talking.

Ben understood, in some slim way, that his mind was creating a “deliberative experience” for him. “The rational choice show” was being played by the projectionist in his head, and he went through all the reasons, thoughtfully and seriously, the pros and the cons, a debate performance where everyone knows the decision has been made already.

Ben understood he was quitting college and moving back to Spokane.

There were so many good reasons to go home. For example, the ash would certainly be heading toward Spokane. Who knew what havoc it would create for his mother and sisters at the Donut Parade?

He would try to win back solid, unmovable Mary Kate , too. He would explain to Angela that his family needed him back home. He would be kind. She would understand. He would pack up his dorm, he would quit his job at the Varsity, and he would say goodbye to his roommate, and he could do all this in a couple of days. He knew he would try to call his mother as soon as he got into the theater. What if they closed the roads? There was so much to do. Ben’s mind became quite busy.

Forty years later, on the anniversary of the eruption, in the wee hours of the morning, Ben was making dough for doughnuts. More than ever did he understand the Cloud of Unknowing. Which was kind of funny because over the years, he and Mary Kate had switched positions, theologically. She had become a religious skeptic, and he gave himself over to the idea that most things were mysteriously pre-arranged. Mary Kate figured it was because he was bad at math. But anyway, they hardly ever argued about it.

Ben had a telescope on the roof of the shop, and when he came to work early enough, he would spend a few minutes looking at the sky.