How Thomas Mann escaped to America and waged a moral battle against Hitler

“I am an American,” Thomas Mann said during a radio interview in 1940. If he sounded relieved, it was because he was: He had been in limbo for years. Mann left Germany in 1933, and the Nazi government deprived him of his German citizenship in 1936. He first took up residence in Switzerland and later became a citizen of Czechoslovakia. As Adolf Hitler’s expansionist intentions became clearer in the late 1930s, Mann must have realized how unsafe it was becoming for him to stay in Europe. The occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939 probably sealed the writer’s decision to move to the U.S. when he was in his 60s.

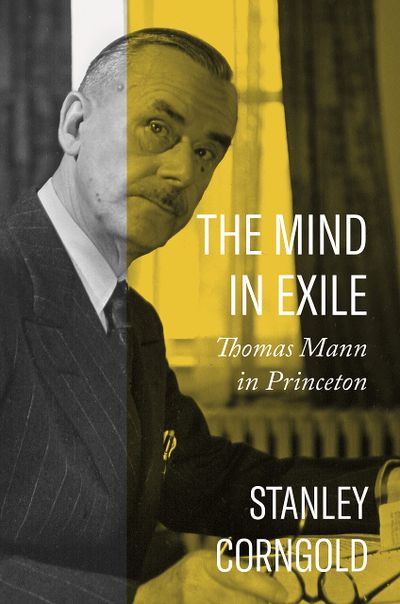

Mann’s first American home was Princeton University, which had already attracted prominent German figures fleeing the Nazis, most famously Albert Einstein. In “The Mind in Exile: Thomas Mann in Princeton,” Stanley Corngold documents, in depth and with an excellent eye for detail, this important stage in Mann’s American life before he moved to California in March 1941. What Corngold, a Princeton professor himself, seeks to achieve is to “shape a cultural memory of Thomas Mann during his American exile in Princeton – a link, by memory, to a continuum between ‘our’ past and present.”

He more than delivers. The picture of Mann that emerges from his book is rich, multilayered and always fascinating. As his friend and fellow exile Hermann Broch observed, Mann had a “stupendous capacity for work,” which allowed him to put his exile to good use. Throughout those years, Mann was highly productive – in several domains simultaneously. There is, first, Mann the academic. The writer had been hired by Princeton to give a series of public lectures in the humanities, as well as some more-specialized seminars.

The lectures’ topics ranged from Goethe’s “Faust” and Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen” to Mann’s own “Magic Mountain,” and they attracted an appreciative audience. The irony must not have been lost on Mann: Here he was, a “lecturer in the humanities” at one of the finest American universities (not to mention the honorary degrees he had received, or would receive, from others) without having ever earned his Abitur (the German high school diploma). But irony was always Mann’s element, both in his work and in his life.

All this time, Mann kept working on his literary projects. During his stay in Princeton, he completed “Lotte in Weimar” (better known in English as “The Beloved Returns”) and wrote an “Indian story” (“The Transposed Heads”), as well as the first chapters of “Joseph the Provider” (the last installment of the tetralogy “Joseph and His Brothers”). For the last, he drew inspiration from New Deal economic policies. Many of Franklin Roosevelt’s ideas about the “national distribution of wealth and commodities” make a cameo in Joseph’s work for the pharaoh.

The most demanding part of Mann’s Princeton life, however, and that which forms the bulk of Corngold’s book, must have been his activism as a public intellectual. He was a political essayist in much demand and wrote for prominent publications such as the New Republic, the Atlantic and the Nation. He also toured the country lecturing on a wide range of topics. And from 1940 until the end of the war, he had a monthly radio program that was recorded in the U.S., flown to England and then broadcast into Germany via the BBC.

Through these efforts, Mann comes across as one of the most prolific and impactful “militant humanists” working against Hitler’s regime from abroad. Life in Germany under the Weimar Republic, and then his years of uncertainty and exile after 1933, had been his schooling in bourgeois humanism and liberal democracy. The same man who, on Sept 18, 1914, spoke of the “great, basically decent, even solemn people’s war of Germany” now savaged the Nazi government for initiating and conducting a completely unjustifiable war.

The German people’s lack of opposition to the Nazis made Mann ashamed of his former country, and he wanted to conjure up a different Germany, one of which anyone could be proud. He ended up finding that country in his own work: “My home is in the works that I bring with me. … They are language, German language and form of thought, personally developed traditional ware of my country and my people. Wherever I am, Germany is.” After the war, Mann would say that his “years of battle against (Hitler) were morally a good time.” He had his reasons to be nostalgic.

His postwar life in America (which is beyond the scope of the book), with the onset of the Cold War and then the McCarthy years, became disappointing. The same “militant humanism” he had employed brilliantly against Hitler now made him look “un-American” to people in power. “I had to get to be 75 years old and live in a foreign country that has become home to me just to see myself publicly called a liar, by burners of witches,” he observed bitterly in 1951. Mann returned to Europe in 1952, never to leave again. Ironically, it was politics that had brought him to America and politics that pushed him away. The mind is always in exile.

Costica Bradatan is a professor of humanities in the Honors College at Texas Tech University. His book “In Praise of Failure” is forthcoming.