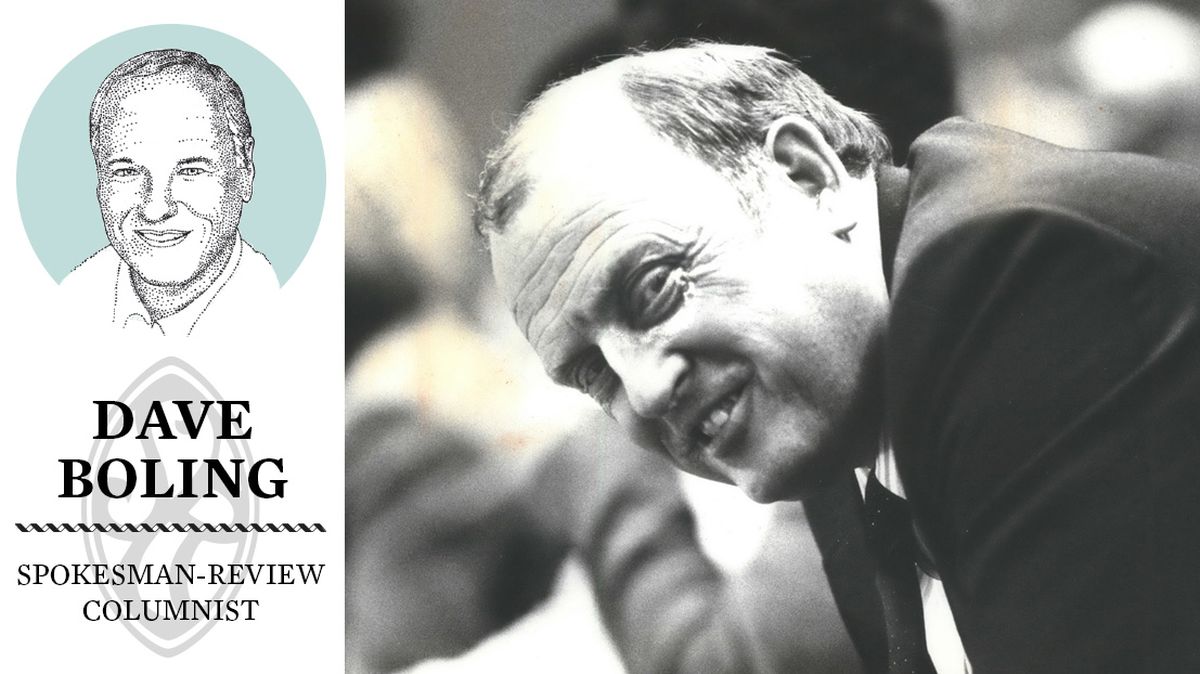

‘A father figure to so many of his players’: Legendary Idaho basketball coach Don Monson dies at 92

Feels a little superfluous to set about eulogizing Don Monson, a man who carved a clear and indelible legacy seemingly every day of his life.

It was always there, in the way he treated people, the way he went about the business of coaching and teaching and mentoring, with respect and dedication, and with a purpose much broader than merely winning basketball games.

Perhaps even more notable than his obvious talents and successes, was the way he accomplished it all with such character and decency.

News of his passing, at age 92, arrived via social media from his son, Dan, basketball coach at Eastern Washington University.

“I’ve lost a great father, my idol, role model, mentor, and, as he would say, Partner.” Dan wrote, reporting that his father died holding the hand of his mother, Deanna.

The Monson basketball roots sprouted in Minnesota, where Oscar “Swede” Monson coached before heading west to Coeur d’Alene. His son, Don, starred at Coeur d’Alene High, and lettered in basketball and baseball at Idaho in the 1950s.

After successes coaching at Cheney and Pasco High, Monson was invited to assist his friend Jud Heathcote at Michigan State University, where he played a significant role in recruiting Hall of Fame guard Magic Johnson.

Calling himself a lifelong Vandal, Monson accepted the challenge of taking over a struggling Idaho program in 1978, and lifted it to unprecedented – and unduplicated – heights.

Under Monson, the Vandals won 43 straight home games in the Kibbie Dome, and in 1981-82, the undersized Vandals won 27 of 30 games to reach the NCAA Tournament Sweet 16 and attain a Top-10 national ranking.

For that achievement, Monson was named National Coach of the Year.

He moved on to the University of Oregon and coached there from 1983 to 1992.

His influence continued long afterward, though, specifically, through Dan, who played a role in building the foundation of Gonzaga as a national powerhouse program, before moving on to Minnesota and later to Long Beach State and EWU.

In a Fathers Day, 2024, article, Dan said that his father’s greatest lesson to him was not in “how to coach,” but “how to BE a coach.”

When asked the distinction between the two, Dan told of a time he remembered tagging along as a kid when his father was coaching at Pasco, and driving to the homes of some of his players who were sick. “… Some families didn’t have money for breakfast, and he brought them orange juice and some other things,” Dan said.

“I could see it was so much more than teaching basketball,” Dan said. “He was a father figure to so many of his players. I learned, because of who you were as a coach, you could impact their lives outside of basketball.”

Gonzaga coach Mark Few, at a recent awards ceremony, claimed that he owed his career to the Monson family.

Few, who has the best winning percentage of any active coach in the NCAA, served as a volunteer at the Monson basketball camp at Oregon, and joined Dan as an assistant at Gonzaga when Dan Fitzgerald was head coach. After Dan Monson left for Minnesota in 1999, Few took over as GU’s head coach, and has taken the Zags to the NCAA Tournament every year since.

When asked what he hoped his father most appreciated about his coaching career, Dan said: “I hope he’s most proud that I did it the right way, with the honesty and integrity that he and mom instilled in me … and being a good coach is being a good person and not breaking rules or cutting corners.”

What better tribute from a son to his father?

Newspaper duties, as an elder sportswriter still telling stories, sometimes involves having to phone other vintage coaches or athletes seeking remembrances from them regarding recently departed friends from their cohort of contemporaries.

Last summer, I’d reached Don for a story about the passing of one of his favorite Vandals, Phil Hopson. “This one really hurt,” he said, voice wavering. “I’m really struggling with this.”

He spoke at the time about how the relationship between a coach and player is a lifelong connection. And that can, eventually, lead to the pain of loss.

A month ago, when former Washington State coach George Raveling died, I called Don for a comment or some insights, the two successful coaches having competed against each other, and had operated in a small geographical sphere.

With no answer, I left a message, and a couple days later, after the Raveling story had run in the paper, Deanna Monson called. She apologized, saying that Don was in the hospital, but he wanted her to call me back so I did not think they had just ignored the call.

There cannot be much clearer evidence of the way “Big Mons” and his family dealt with people than his wife returning a call while in the midst of a family health crisis.

That is an example of why the sorrow in the basketball community over his passing has little to do with Don Monson’s coaching achievements, and is so much more about his unwavering humanity.