Schooled at St. Patrick’s

Like a family heirloom, St. Patrick’s Catholic School has touched four generations of Margaret Weaver’s family.

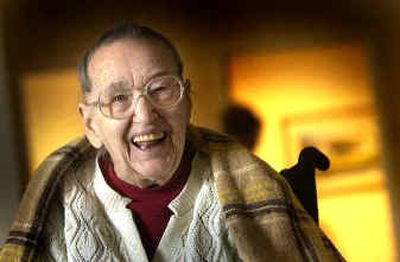

Weaver, 91, was a student there in the 1920s. That’s where she sent all five of her children, and where her children sent their children. Now, even her great-grandchildren have occupied desks and wandered the halls of the old, brick school in Hillyard.

“It’s been a huge part of our family,” said Julie Farmer, Weaver’s daughter and a 1955 St. Pat’s graduate.

Established nine decades ago, a year before the creation of the Diocese of Spokane, St. Pat’s has kept its identity as a close-knit, neighborhood school, an institution where students follow in the footsteps of their parents and grandparents, and a place that still reflects the working-class values of the old railroad families in Hillyard.

On Saturday, some of the roughly 4,500 students who have graduated from St. Patrick’s since 1914 will return to their alma mater for an all-class reunion. Among the oldest who plan to attend is Weaver, a 1927 graduate who now lives at Riverview Retirement Community in north Spokane.

Students at St. Pat’s not only live in the same neighborhood; like other Catholic school kids, they stay together from kindergarten, sometimes pre-school, all the way through eighth grade.

The intimacy fostered at St. Patrick’s over the years created a lasting bond that kept classmates in touch, even years after graduation, said Pat Bauer, Weaver’s oldest child and a 1951 grad. “We have a shared history,” she said.

Classrooms at St. Pat’s and other area schools once teemed with hundreds of young people. Today, the student population at the Hillyard school hovers around 190.

Locally and nationwide, Catholic school enrollment has seen a slight drop. Although the population in the Spokane Diocese’s 15 elementary schools and DeSales High School in Walla Walla remained steady at 3,500 during the past two years, it did experience a 1 percent to 2 percent decrease in the two years prior to the 2002-2003 school year.

Part of that is due to demographics. The enrollment decline in urban Catholic schools and the slight increase seen by the suburban ones reflect the shift in student population that public schools also have seen in recent years. While some Catholic schools in central Spokane are losing students, Assumption and St. Thomas More on the North Side, as well as St. Mary’s in the Valley, have a waiting list.

Mirroring the growth in Kootenai County, Holy Family Catholic School in Coeur d’Alene is experiencing a boom. When it began as a kindergarten through third grade school nine years ago, Holy Family had only 53 kids. Now, it has expanded and offers pre-school to eighth-grade education. Holy Family also has more than 230 students and is in the process of erecting a new building.

Duane Schafer, superintendent of the Spokane Diocese’s schools, believes the decrease in enrollment could be due to cost.

“Financially, with the economy, it’s been a real challenge to families,” said Schafer, who has worked in Catholic schools for 36 years.

The average per-pupil cost of a Catholic education is $3,800 a year, according to Schafer. Actual tuition prices vary – some schools offer need-based scholarships while others use the “fair share” method, by asking parents to volunteer at the school and pay what they can afford.

Catholic schools still generate most of their income from tuition, although a small percentage – roughly 15 percent to 18 percent – is subsidized by money from the Sunday offering plate at surrounding parishes.

To ensure the survival of schools like St. Patrick’s and to allow kids who might not be able to afford tuition to attend the school, parents, alumni and staff participate in major fund-raisers.

“Anyone who wants a Catholic education is welcome here,” said Marcia Parks, a St. Pat’s alumna, past parent and the school’s development director. “Our mission is to serve everyone.”

Many of the St. Patrick students come from single-parent and low-income homes, according to Parks. Forty percent of the families aren’t Catholic. Very few actually pay the full $3,700 tuition. Support from donors makes all the difference, Parks said.

Weaver, who has 16 grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren, wouldn’t have been able to attend St. Pat’s if it hadn’t been for the kindness of the priests and nuns who ran the church and school.

When she was 5 years old, her father died on the railroad tracks after being struck by a steam locomotive. To help the family get back on its feet, the church gave them a place to live. In fact, the house where they stayed was on the same spot where the school was eventually built. Weaver’s mother ended up getting a job cleaning St. Patrick’s Church.

Over the years, the church and the school became Weaver’s second home, she said. It was where she married Harry Weaver, her husband of 66 years until he died two years ago. It was where she raised her children.

Even now, Weaver and her kids share many fond memories of their years at St. Patrick’s.

Tom Weaver, 61, recalled the smell of the incense and the growl of his stomach as he served as the altar boy during the 5:30 a.m. Mass. Back then, many of the railroad workers had to go to work at 7 a.m. on Sundays, so church started early. People also were very strict about the one-hour required fast before communion, so Tom was always hungry during Mass. “You couldn’t even drink water,” he said.

Farmer, 62, remembered the strict rules enforced by the nuns. Kids who talked during class were sent to the cloakroom, where they stood until recess. Gum chewers were forced to take the wad out of their mouths and stick it to their noses. Girls had to dress modestly, she recalled, and sat on the opposite side of the boys during Mass.

On the walk home from school, some of the non-Catholic kids would tease them and call them “Cat-lickers,” Farmer recalled with a laugh.

Among Margaret Weaver’s memories are the salt-and-pepper-colored corduroys worn by her sons to school – “They were so hard to wash,” she said – and the sisters who taught her in the classroom.

“You never forget them,” she said. “They never forget you either.”