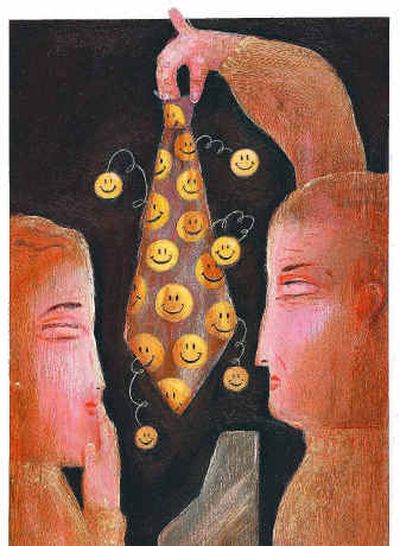

Germs hitch a ride on neckties

Many patients prefer that their doctors wear ties — which creates a professional appearance — but probably don’t think about where those ties have been.

Doctors straighten them and fiddle with them between hand washings, the ties brush against patients’ skin during examinations, and they get sneezed on and coughed on by patients.

Each encounter can leave microbes on those strips of fabric.

Although researchers have assessed the germ-carrying potential of stethoscopes, cellphones, even pens, it took a medical student to realize doctors’ ties might carry germs as well.

Steven J. Nurkin was doing an elective course in surgery at a New York teaching hospital last September when he noticed that ties had a way of peeking through doctors’ white coats and swinging in front of patients.

A tie “may be coughed on, come in contact with bedding or even have direct contact with the patient,” he said. “I thought that the necktie might have the potential for harboring pathogens, and even help in transmitting them.”

So Nurkin devised an experiment, in which he and fellow researchers took swabs from 42 ties worn by male doctors, physicians’ assistants and medical students at New York Hospital Queens on three randomly selected days.

The medical staff worked in surgical, medical and cardiac intensive care units, as well as on surgical and medical floors. For comparison, the researchers tested ties worn by 10 security guards who walk the hospital corridors but don’t get as close to patients as doctors.

When Nurkin and his colleagues studied the samples, 20 ties sported by medical professionals tested positive for one or more germs; only one tie from a security guard tested positive.

A dozen health workers’ ties (and the aforementioned guard’s tie) tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that usually lives harmlessly inside the nose and on the skin but can cause a variety of infections in vulnerable people.

Seven ties contained organisms that could pose a threat to the elderly or others weakened by illness or medication, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Alcaligenes faecalis and Pantoea agglomerans (which turned up on three ties).

Another tie tested positive for a common mold called aspergillus.

Although Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common hospital-acquired infections, often occurring in hard-to-treat, drug-resistant form, none of the bacteria found on the ties was resistant to methicillin and related antibiotics.

That was good news to Nurkin’s co-author, Dr. James J. Rahal, the hospital’s head of infectious diseases, who explained that the study was designed to see whether the most harmful and most difficult bacteria are on the ties.

As for the microorganisms that were detected, about 50 percent of the world’s population — and 50 percent of hospital patients — already have these bacteria, he said.

“The question of whether or not the ties are increasing the risk of patients developing infections from these bacteria is anything but settled,” Rahal added.

Although the researchers found no direct evidence that germy neckties actually cause infection, the findings suggest the potential for bacterial spread, at work and at home.

With many of those ties going home, anyone who touches them also runs the risk of being exposed to the bacterial remains of the day.

Because most ties are dry-clean-only garments, they often don’t get cleaned until they become visibly soiled or stained.

Nurkin’s experiment didn’t track bacterial life spans on fabric, but some studies have shown that germs called enterococci can live as long as 18 hours on bedsheets.

Since he began his experiment, Nurkin said, he’s heard suggestions that it’s time to “bring back the bowtie.”

“Someone else suggested a tie tack that attaches to the shirt. And someone actually suggested a necktie prophylactic, and, of course, abandoning the necktie,” he said.

Although studies have shown that patients prefer the more formal look, the findings raise the question of whether the neckwear is in the patients’ best interest.

The findings were presented recently at the 104th general meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in New Orleans.

As for Nurkin, he’s receiving his medical degree from the American Technion program in Israel — where, he said, doctors rarely wear ties.