Prequel to ‘The Hate U Give’ eviscerates stereotypes about Black families

I will never forget the day I learned that my older cousin was pregnant. I was on the verge of turning 8, and the auntie who shared the news delivered it with this hint of foreboding – like a cautionary tale. Because my cousin was “only” 15.

Fast-forward: It’s 2018. I’m 32, married eight years with two planned-for and deliberately conceived children. I’m visiting an ultra-rich, glaringly white private school to give a talk on my debut novel, “Dear Martin.”

I’m standing at the front of a room with 150 (ultra-rich, glaringly white) kids talking about the connection between systemic racism and implicit bias. A young woman sitting in the front row raises her hand.

“But what about the illegitimacy rate?” she asks.

“The what now?” I say.

“The illegitimacy rate,” she repeats. “You know: the rate of African American kids who grow up without fathers.”

I responded with a question: “Honey, what exactly makes a person ‘illegitimate’?”

The experience will stick with me forever. It wasn’t just the flagrantly offensive nature of the question that got under my skin. It was the confidence with which she asked it.

How certain she was that the “illegitimacy rate” was a concept that could be used to rebut the need to examine and dismantle anti-Black racism.

I have long known of the stereotypes that pervade American notions of the Black family. There’s the stereotype of the “fast” (read: promiscuous and hypersexual) Black girl who gets knocked up as a teenager. The stereotype of the absentee Black father – the Bailing Baby Daddy. There’s the stereotype of the “broken home” and the presumption of single motherhood and multiple fathers if there are multiple children.

The problem with these stereotypes is the problem with all stereotypes: They create false, large-scale ideas about large groups of people and strip living, breathing human beings of their complexity and humanity.

Enter Angie Thomas. In 2017, Thomas’s smash hit “The Hate U Give” introduced us to a Black “traditional” family – a unit formed by a heterosexual married couple and their shared biological children – with a caveat: The eldest child in the Carter family, Seven, has a different birth mother than his siblings, Sekani and Starr.

We also learn Seven and Starr are just over a year apart, which would certainly raise a red flag for the illegitimacy police. In order for siblings to be that close in age, one had to be a baby when the other was conceived.

And since we also know Starr’s mother, Lisa, was 18 when she gave birth to Starr, and that Lisa and Starr’s father, Maverick Carter, are the same age, it’s not difficult to deduce that good ol’ Maverick impregnated two girls as a teenager.

It’s clear things worked out: When we meet Maverick in “The Hate U Give,” he’s a successful entrepreneur, happily married to Starr’s mother, and doing everything in his power to lead and provide for his family. Yes, he was once a gang member and drug dealer, but he’s left all that behind. He is not only present, he’s persistent. Precisely the type of Black dad people presume doesn’t exist.

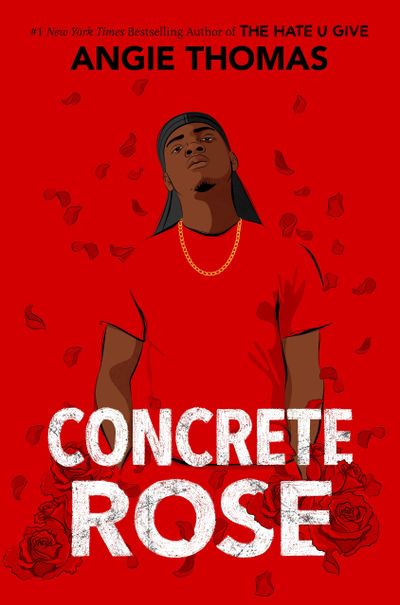

But one of my favorite things about Angie Thomas (whom I know through work events) is she’s willing to dig deeper, to peel back another layer. This is what makes her latest novel, “Concrete Rose” – her best, in my opinion – a gift. It not only eviscerates the “fast Black girl” stereotype and debunks the myth of the Bailing Black Baby Daddy, it gives us insight into the life of a boy most people wouldn’t attempt to look at beyond the surface.

In “Concrete Rose,” we get to dive into the life of young Maverick Carter. The demonized elements of his life are salient: He’s a gang member and a drug dealer who manages to impregnate two different girls before he’s halfway through his senior year of high school. And Thomas doesn’t sugarcoat this: She lets us see the grit and grime of all of it.

But Thomas does not permit the reader to perch up on a pedestal of unexamined moral ideals (like “illegitimacy rate”) and look down on the characters in this book – and the people they represent in the real world – from some completely position of superiority.

One of Thomas’s greatest skills is crafting characters that give even adults readers insight into their younger selves.

She makes us remember what it’s like to feel as though you can’t speak up without dire consequences; what it’s like to have dreams so much bigger than you are; what it’s like to be stuck between a rock and a hard place with no idea what to do, but also no choice but to figure it out.

No, gang membership, drug slinging and teen parenthood aren’t light or easy topics. But in “Concrete Rose,” Thomas handles them with utmost care, compassion and nuance. It’s a novel that, like Thomas’s other books, plucks at the strings of our complex humanity.

It’s almost as though Thomas gets right in the reader’s face and says, “No. I will not allow you to dehumanize other people just because you ‘don’t agree’ with how they live or the decisions they make. Let’s put you in their position and see what you would do.”

And it’s for this reason we all owe Angie Thomas a debt of immense gratitude. Because in allowing us to see the heart and soul of a boy who does just about everything our society vilifies, but is truly doing the best he can with what he has, she has given us the greatest gift of all: permission to let our guards down and be a little more legitimately human.