Book review: A pioneering Black author’s novel takes us to a Wakanda-like civilization

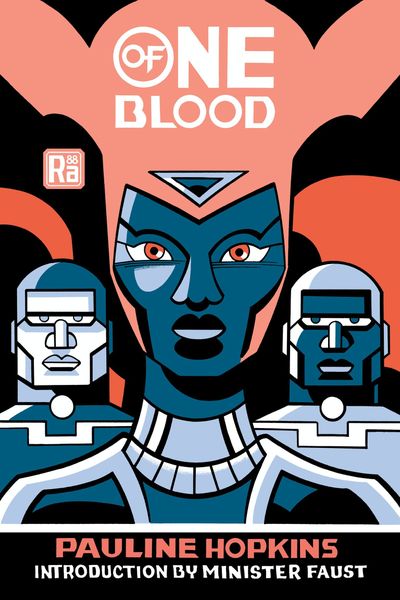

Pauline Hopkins’ “Of One Blood,” first published in 1903 as a serial in Colored American Magazine, reappears now as a paperback, with highly stylized cover art, in Joshua Glenn’s admirable “Radium Age” series devoted to early-20th-century science fiction and fantasy. Previous “Radium Age” titles, all published by MIT Press, include J.D. Beresford’s “A World of Women” (1913), E.V. Odle’s “The Clockwork Man” (1923) and J.J. Connington’s “Nordenholt’s Million” (1923). I’ve read all three and highly recommend them.

Hopkins was a pioneering Black intellectual, playwright and magazine editor who used her considerable literary talents to rally support for the cause of racial justice. In “Of One Blood,” the last of her four novels, she blends multiple subgenres into what is an exceptionally entertaining work of popular fiction, albeit one with a serious subtext: race.

Set in Boston in what must be the 1880s, “Of One Blood” focuses on Reuel Briggs, a brilliant, penniless and moody young medical researcher who is strongly drawn to the secret knowledge found in alchemical texts. No one knows much about his background, but he is thought to be of Italian descent. His only close friend, Aubrey Livingston, bears “the beautiful face of a Greek god” and is, in fact, the devil-may-care scion of an old Virginia family.

One night, these two friends attend a choral concert presented by students from Fisk University, the headliner being a dazzling soprano named Dianthe Lusk. “She was not in any way the preconceived idea of a Negro. Fair as the fairest woman in the hall, with wavy bands of chestnut hair, and great, melting eyes of brown, soft as those of childhood; a willowy figure of exquisite mould, clad in a somber gown of black.” Reuel immediately recognizes her as the woman he has glimpsed in a recent mystical vision.

A few weeks later, on Halloween, Aubrey’s fiancee, the spirited 18-year-old Molly Vance, reveals that a ghostly woman in white can sometimes be seen wandering the grounds of the house next door. That night, Reuel encounters this spectral vision, whom he recognizes as Dianthe Lusk.

Up to this point, “Of One Blood” might well be a Gothic novel, tinged with spookiness and mystery. Reuel could almost be a latter-day Victor Frankenstein when he draws on his occult knowledge to restore life to a corpse-like hospital patient given up for dead. There’s also more to the young scientist than meets the eye. Aubrey alone knows that his friend won’t be crossing the color line by falling in love with Dianthe Lusk. Unfortunately, Reuel isn’t the only one infatuated with the beautiful singer.

The book’s first section is dominated by images of Whiteness. In its middle chapters, the novel turns to the “Afritopian” element stressed by science fiction writer Minister Faust in his biographically informative – and angrily impassioned – prefatory essay: At one point, Faust alludes to “imperialist scouts for mass-murdering kleptocrats,” adding: “Schoolbooks call them ‘explorers.’” (If you’re sensitive to spoilers, Faust’s introduction reveals too much of Hopkins’s plot, as does the paperback’s back cover. Both should be read after you’ve enjoyed the novel.)

Throughout her narrative, Hopkins regularly quotes Shakespeare, Longfellow and other poets but also seems to be well read in the subgenre known as the Lost World or Lost Civilization Romance. Established by H. Rider Haggard in “She” (1886) and “Allan Quatermain” (1887), its most famous modern example is James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon” (1933), which gave us Shangri-La. In these novels, a legend, a map or a dying man’s confession reveals the existence of an unknown kingdom, somewhere largely inaccessible, where an ancient civilization survives, hidden from the modern world. There, its priests or sages possess powers far beyond any of those we know. More often than not, its people are also awaiting or fearing the fulfillment of a centuries-old prophecy. For instance, in Gilbert Collins’s “The Valley of Eyes Unseen” (1924), the hero turns out to be the long-promised reincarnation of Alexander the Great.

In Hopkins’s novel, Reuel, desperately needing money, joins an expedition to Africa, searching for a fabulous treasure. En route, he learns about the advanced technological and cultural achievements of the long-vanished Ethiopian kingdom of Meroe. But has this Wakanda-like civilization really disappeared? As Reuel eventually discovers, “in the heart of Africa was a knowledge of science that all the wealth and learning of modern times could not emulate.”

In her book’s first act, Hopkins seems to be re-creating a classic Gothic romance; in its second, she offers a suspenseful Lost World adventure; and in the third, she boldly updates Greek tragedy, as the South’s racist history embroils her main characters. Ultimately, the white, or seeming white, of Boston and the Black of Africa commingle, when she brings her color-themed plot to a thrillingly melodramatic finish.

At one point, the metaphysically minded Reuel confesses that he longs to solve the mystery of “the whence and whither” of our earthly existence. In her turn, Hopkins – who died in 1930 at age 71 – longed to dismantle what we now call systemic racism, in part by stressing our common humanity. As God, in her book’s New Testament-derived epigraph, firmly declares: “Of one blood I made all nations of man.”