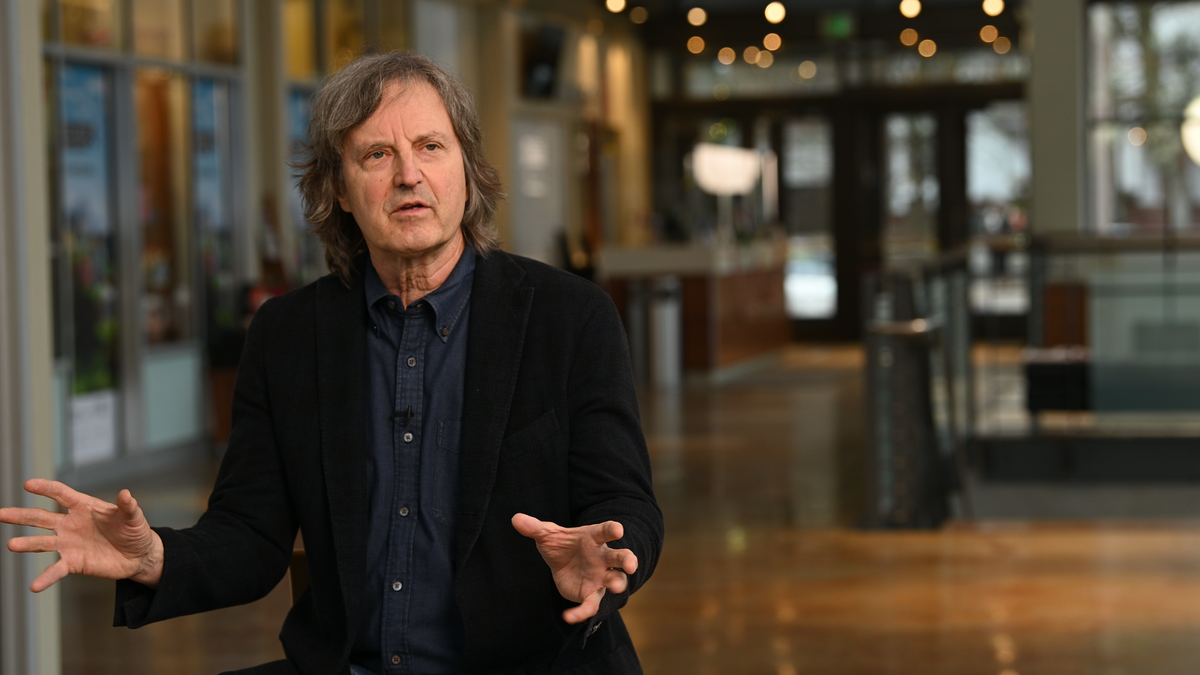

Lewis and Clark alumnus, prominent Seattle architect tips his cap to Harold Balazs

When Tom Kundig returned to the South Hill for his father’s funeral last month, the revered Seattle architect couldn’t help but reminisce. Kundig chuckled as he recalled leaving home for the University of Washington just over a half-century ago.

“I remember thinking then that the best view of Spokane was in the rearview mirror,” Kundig said. “All kids feel that way when it’s time to leave home, since they all want to have an adventure and my adventure was in Seattle.”

But Kundig, 69, notes that the formative years in his hometown helped him forge his path. Kundig tips his cap to his father, Moritz Kundig, also an esteemed architect and legendary local artist Harold Balazs.

When Kundig returned to his hometown in February he visited the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture for the Balazs exhibit, “Harold Balazs: Leaving Marks,” which runs through June 2, to speak at a donor event.

“I’m a full supporter of what’s happening at the MAC, especially Harold’s archives,” Kundig said from his Seattle office.

Kundig contributed to the collection purchase of 30 mixed-media works, which includes sculptures in copper, lead, wood, metal and styrofoam.

“It’s the least I can do, since what Harold created should remain in Spokane,” Kundig said. “I’m compelled to help, since Harold was such a powerful influence. I can’t go through a day without acknowledging his impact on my life and my success as an architect.”

The principal of Olson Kundig Architects earned an American Institute of Architect award for a striking cabin at Chicken Point on Hayden Lake. Kundig designed the stunning Winescape Winery, the raw and refined Pierre in the San Juan Islands and many other acclaimed projects.

“What impacted me from Harold was his risk-taking, curiosity, creativity and enthusiasm,” Kundig said. “All of that rubbed off on me.”

Kundig met Balazs, who passed away at 89 in 2017, when he was 5 years old and started working with the iconic artist at 12.

“At least he can’t get hit for child labor laws now,” Kundig cracked. “I was very young when we met. It struck me very early on that Harold was this force of nature, who fortunately existed in our community.”

Moritz Kundig and Balazs were friends, and Tom Kundig reaped the rewards of their relationship.

“Harold was a very funny guy, who was always getting into adventures,” Kundig said. “He was a very smart man who went out on a limb in the world of art. At that time, he was doing some work for (the department store) Joel (Inc.) and was living on the South Hill.

“I would go over to his shop and observe, but before long I was working with him and it was such a joyful experience.”

Balazs moved to Mead during the 1970s, and teenage Kundig visited often.

“I spent a lot of time out there swimming in the creek,” Kundig recalled. “I was surrounded by the beauty of the area, Harold’s art and character.”

What Balazs impressed upon the pubescent Kundig was his endless drive.

“What I saw at Mead was a man who was tireless,” Kundig said. “He was just so passionate about his art and he would devote endless hours to it. I learned from him that when things go bad, well that’s when you put your shoulder into your work and grind. I’ve had to do that so much throughout my career.”

Kundig recalls being impressed with Balazs’ outlook on life.

“Harold was such an optimist, and that’s not easy when you’re in the arts, since you often have your soul crushed. but you have to work your way through it,” Kundig said.

Kundig’s work ethic was impacted by his father, who died at 98.

“He was a wonderful man,” Kundig said. “He was just different from Harold, who was an extrovert. My dad was an introvert, but I enjoyed speaking with him over recent years, since we spoke as architect to architect, colleague to colleague.

“It was the end of an era with my father. He passed away in his sleep peacefully and that’s the way he wanted to go. But he lived a long, full life.”

Kundig was born and raised in the Manito Park area. When he left for college, his father built a house close to the Perry Street stairs on the South Hill.

“I always enjoyed coming back home,” Kundig said. “What’s great is that it was always only on the other side of the state. I would see my father and Harold when I returned.”

Kundig plans to come back often to visit Balazs art at the MAC.

“I’ll always be a big supporter of the MAC,” Kundig said. “That’s especially so with Harold’s art there. Everyone should experience what he did. His pieces at the MAC are incredible.”

The MAC collection features Balazs’ “Trying to Understand,’ a ground-breaking 96-inch tall sculpture, created by using a styrofoam base that the artist coated with graphite. Another untitled sculpture was carved from lead. Balazs’ industrial background inspired his use of affordable materials not commonly used by other artists.

“Leaving Marks” is broken down into three sections. “Constructed Realities,” “Making/Life” and “Transcend the Bullshit.”

“Constructed Realities” is an overview of Balazs’ industrial roots. “Making Life” explores how Balazs was inspired by everyday situations. “Transcend” is about Balazs’ philosophical side and his playfulness.

“Harold’s work is unlike no other,” Kundig said.

Kundig will also return to the Inland Northwest to restore his father’s cabin on Coeur d’Alene lake.

“It’s beautiful out there,” Kundig said. “So many great memories run through my mind when I come back.”

The take is different than it was for Kundig months after graduating Lewis and Clark High School in 1972. Seattle will occasionally be in the rearview when Kundig drives east on Interstate 90.

“I guess life has gone full circle for me,” Kundig said.